The study shows new prospects for growing human organs needed for transplant in animals.

- Up until now, researchers have been looking for ways to grow new human organs inside animals.

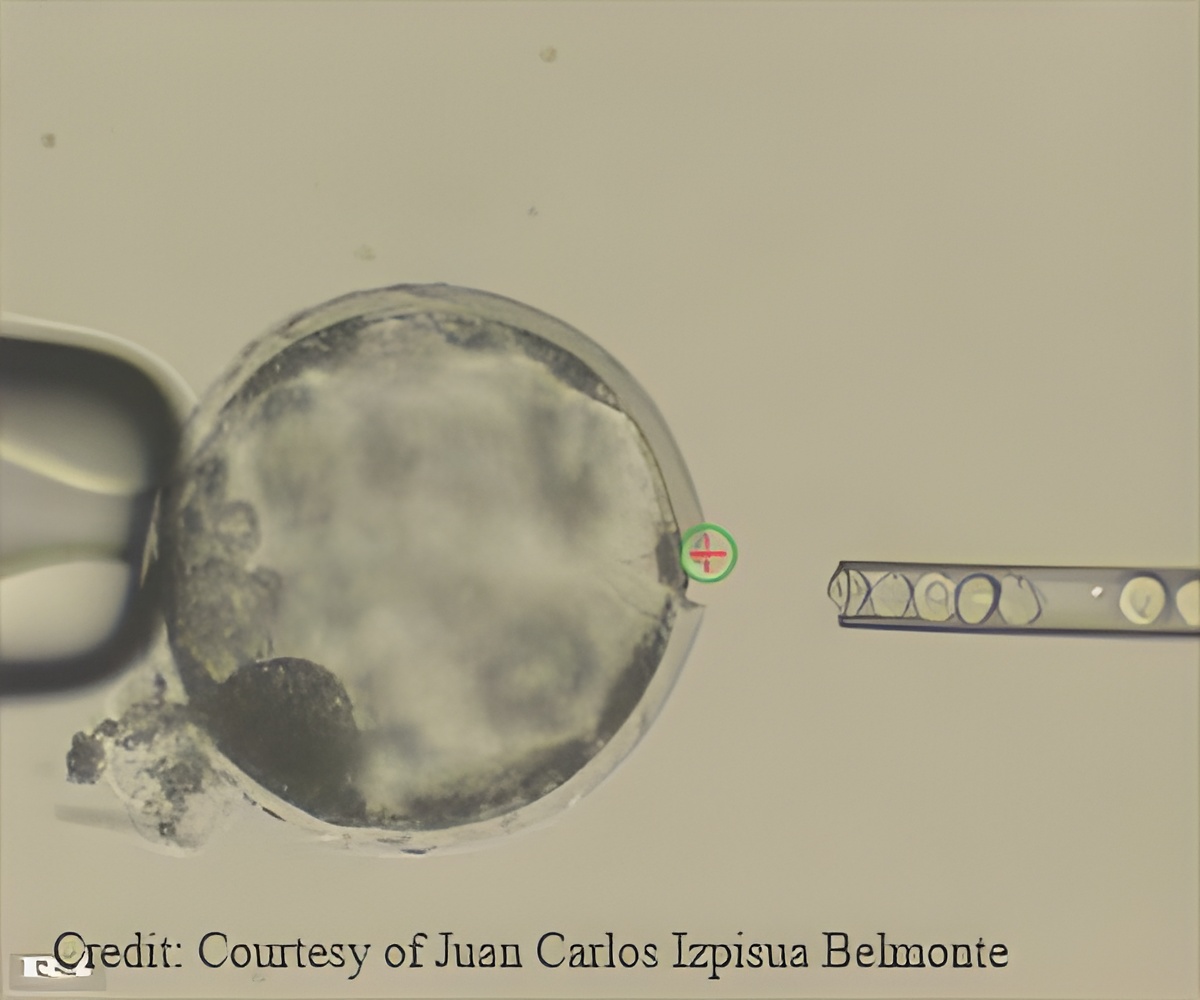

- But in a recent study, scientists have successfully demonstrated how to inject human stem cells into pig embryos.

- These human/pig chimeras can aid in developing human organs needed for transplant in future.

The approach involves growing the desired new organ in a large animal like a pig using human stem cells, and then harvesting it for transplant into the patient’s body.

The risk of immune rejection would be small in such cases because the organ would be made of a patient’s own cells.

Chimeras are animals composed of two different genomes and the human-organ-growing pigs would be an example. They would be generated by implanting human stem cells into an early pig embryo, resulting in an animal composed of mixed pig and human cells.

A team of biologists, led by Jun Wu and Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte at the Salk Institute, has shown for the first time that human stem cells can contribute to forming the tissues of a pig.

"It's like when you try to duplicate a key. The duplicate looks almost identical, but when you get home, it doesn't open the door. There is something we are not doing right," says Izpisua Belmonte. "We thought growing human cells in an animal would be much more fruitful. We still have many things to learn about the early development of cells."

As a first step, Izpisua Belmonte and Salk Institute staff scientist Jun Wu created a rat/mouse chimera.

They did this by introducing rat cells into mouse embryos and letting them mature.

To allow the rat cells to grow in specific developmental niches in the mouse, researchers conducted genome editing .

They used CRISPR genome editing tools to delete critical genes in fertilized mouse egg cells. For instance, in a given cell, they would delete a single gene critical for the development of an organ, such as the heart, pancreas, or eye. Then, they introduced rat stem cells into the embryos to see if they would fill the open niche.

"The rat cells have a functional copy of the missing mouse gene, so they can outcompete mouse cells in occupying the emptied developmental organ niches," says Wu. As the organism matured, the rat cells filled in where mouse cells could not, forming the functional tissues of the organism's heart, eye, or pancreas.

In rats though the gall bladder stopped developing 18 million years ago, in the experiment, the rat cells also grew to form a gall bladder in the mouse.

"This suggests that the reason a rat does not generate a gall bladder is not because it cannot, but because the potential has been hidden by a rat-specific developmental program," says Wu. "The microenvironment has evolved through millions of years to choose a program that defines a rat."

Second Step-Human/Animal Chimeras

The team's next step was to introduce humans' cells into an organism.

Due to their large size and close resemblance of their organs to humans, they decided to use cow and pig embryos as hosts.

The scientific challenge faced by the researchers was in determining what kind of human stem cell could survive in a cow or pig embryo.

Hurdles faced

The researchers chose pigs due to the difficulty and cost involved in experimenting with cows.

The effort required to complete studies of 1,500 pig embryos involved the contributions of over 40 people, including pig farmers, over a four-year period. "We underestimated the effort involved," says Izpisua Belmonte. "This required a tour de force."

Pigs also have a gestation period that is about one-third as long as humans, so the researchers needed to introduce human cells with perfect timing to match the developmental stage of the pig.

"It's as if the human cells were entering a freeway going faster than the normal freeway," says Izpisua Belmonte. "If you have different speeds, you will have accidents."

Several different forms of human stem cells were injected into pig embryos to see which would survive best. The "intermediate" human pluripotent stem cells were the cells that survived longest and showed the most potential to continue to develop.

The so-called "naïve" cells resemble cells from an earlier developmental origin with unrestricted developmental potential; "primed" cells have developed further, but still remain pluripotent. "Intermediate cells are somewhere in between," says Wu.

The human cells survived and formed a human/pig chimera embryo. It did help to form their organs, although not very efficiently.

The researchers did not want the human/animal chimera to be too human. That is, they did not want human cells to contribute to the formation of the brain. In this study, the human cells did not contribute to formation of brain cells that can grow into the central nervous system. Rather, they were developing into muscle cells and precursors of other organs.

"At this point, we wanted to know whether human cells can contribute at all to address the 'yes or no' question," he says. "Now that we know the answer is yes, our next challenge is to improve efficiency and guide the human cells into forming a particular organ in pigs."

The researchers said there was a long way to go before human organs could successfully be grown in animals like pigs.

The report is published in in Cell.

Reference

- Jun Wu et al. Interspecies Chimerism with Mammalian Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell ; (2017) doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.036

Source-Medindia