A study was conducted to assess the effectiveness of outpatient care for pulmonary embolism patients and proves that it is not inferior to inpatient care.

The aim of the study was to assess the effectiveness of outpatient care for PE patients and prove that it is not inferior to inpatient care.

In a recently publicized study by Drahomir et al an open-label, randomized non-inferiority trial was conducted at 19 emergency departments in the USA, Switzerland, France and Belgium.

Between February, 2007, and June, 2010, 344 eligible patients with acute, symptomatic pulmonary embolism were enrolled in the study. The patients were 18 years or older.

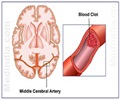

The researchers defined pulmonary embolism as the acute onset of dyspnea or chest pain, along with a new contrast filling defect on computed tomography or pulmonary angiography or a new high-probability ventilation-perfusion lung scan. It may also be a documentation of a new proximal deep vein thrombosis either by venous ultrasonography or contrast venography.

The patients were randomly assigned to two categories -

• Inpatient treatment with subcutaneous enoxaparin for approximately 5 days followed by oral anticoagulation for about 90 days.

The pulmonary embolism severity index is a clinical prognostic model that was created and validated in over 16 000 patients with pulmonary embolism.

Patients with one or more of the following characteristics were excluded:

• Arterial hypoxemia

• Systolic blood pressure of less than 100 mm Hg

• Chest pain necessitating parenteral opioids

• Active bleeding

• Those with high risk of bleeding (defined as stroke during the preceding 10 days, gastrointestinal bleeding during the preceding 14 days or fewer than 75 000 platelets per mm3)

• Severe renal failure (creatinine clearance of <30 mL per min based on the Cockcroft-Gault equation),

• Extreme obesity (body mass >150 kg),

• History of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia or allergy to heparins, therapeutic oral anticoagulation at the time of diagnosis of pulmonary embolism

• Any barriers to treatment adherence or follow-up (eg, current alcohol abuse, illicit drug use, psychosis, dementia, or homelessness),

• Pregnancy

• Imprisonment

• Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism more than 23 hrs before screening time (to avoid enrolling already stabilised patients)

• Previous enrolment in the trial.

In both treatment groups, early initiation of oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists such as (warfarin, acenocoumarol, phenprocoumon, or fluidione) was recommended along with its continuation for a minimum of 90 days.

All patients were contacted every day for the week after enrolment and at 14, 30, 60, and 90 days and were asked about symptoms of recurrent venous (VTE) such as dyspnoea, chest pain, leg pain, swelling, bleeding, and any use of health-care resources. All patients were instructed to report about any new symptoms suggestive of VTE.

Results & Discussion - In selected low-risk patients with pulmonary embolism, outpatient care can safely and effectively be used in place of inpatient care.

The study revealed that outpatient treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin is not inferior to inpatient treatment in terms of effectiveness and safety.

The study demonstrated that out - patient care was well received by patients who were equally satisfied with their care as were the inpatients.

Another beneficial factor was that outpatient treatment also reduced hospital time.

Reference:

“Outpatient versus inpatient treatment for patients with acute pulmonary embolism: an international, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial”

Drahomir et al

The Lancet, Volume 378, Issue 9785, Pages 41 - 48, 2 July 2011

Source-Medindia

![Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension [PAH] - Symptoms & Signs - Causes - Diagnosis - Treatment Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension [PAH] - Symptoms & Signs - Causes - Diagnosis - Treatment](https://images.medindia.net/patientinfo/120_100/pulmonary-arterial-hypertension-pah.jpg)