Fasting or eating little to no food or caloric drinks over anywhere from 12 hours to a few weeks prevents disease and slows aging.

- Limiting calorie intake has shown to slow down aging in mice but was not tested in humans.

- Recent studies done to show the benefits of calorie restriction by fasting for few times a month has brought to light some vital findings.

- Fasting mimicking diets helps in weight loss, slows aging, improves insulin secretion and reduces the risk of diabetes, high blood pressure.

Now, the second phase of the Comprehensive Assessment of Long-term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy (CALERIE 2) trial, demonstrated that it’s feasible for humans to limit calories for an extended period.

Participants who cut back on calories lost weight and kept it off for the duration of the study. There were no adverse effects on quality of life and the participants netted improvements in blood pressure, cholesterol, and insulin resistance—all risk factors of age-related diseases.

It’s still an open-ended question whether dietary intervention—or any intervention at all—can dramatically extend humans’ maximum lifespan. But epidemiological evidence and cross-sectional observations of centenarians and groups that voluntarily cut their calories strongly suggest that the practice could help people extend their average lifespan and live healthier, as well.

The Ways we Can Restrict Calories

Like caloric restriction, fasting—eating little to no food or caloric drinks over anywhere from 12 hours to a few weeks—has been shown to prevent disease and slow aging in a range of organisms.

Fasting Mimicking Diet - An Easier Method To Go Easy on Calorie Restriction

The diet was developed by Valter Longo, PhD, a professor of gerontology and biological sciences at the University of Southern California and head of the Longevity Institute there. He has studied caloric restriction’s protective effects on aging and disease since the early 1990s.

In a 2011 NIA-cofunded study of young overweight women, a weekly fast—5 days of unrestricted eating and 2 consecutive days of 75% caloric restriction—produced outcomes similar to daily caloric restriction in reducing weight, total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and blood pressure, among other markers.

Less severe energy restriction could provide bigger improvements with fewer fasting days per month. In the trial, dieters only had to restrict their calories 60% for 5 consecutive days a month over 3 months to get the benefits of the so-called “fasting-mimicking diet.”

The fasting-mimicking diet is commercially available as a 5-day meal plan. The plant-based diet provides approximately 1100 calories on day 1 and around 750 calories on days 2 through 5. It’s low in proteins and carbohydrates and rich in healthful fats.

Longo initially tested his diet in middle-aged mice, subjecting them to 4 consecutive days of the fast twice a month until their deaths. Mice on the diet lived an average of 11% longer than control mice—28.3 months vs 25.5 months—and had fewer cancers, less inflammation, less visceral fat, slower loss of bone density, and improved cognitive performance.

In the same study, Longo also tested the diet in a small pilot clinical trial. After 3 monthly cycles of a 5-day fasting-mimicking diet, the 19 generally healthy participants in the intervention group reported no major adverse effects and had decreased risk factors and biomarkers for aging, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer compared with the control group, which maintained its normal caloric intake.

Those results were confirmed in Longo’s larger phase 2 trial, which enrolled 100 generally healthy participants. In the new study, the control group was crossed over to the dieting intervention after 3 months. In the end, 71 participants completed 3 consecutive cycles of the diet.

About a week after the end of the third cycle in the randomized arm of the study, the intervention group had lost an average of approximately 6 pounds while the control group had not lost weight.

Dieters also had less trunk and total body fat, smaller waist circumference, and lower blood pressure and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels compared with the control group. In the crossover arm of the study, the intervention had comparable effects.

The diet appears to help more those who need it the most, Longo said. Its effects on blood pressure and IGF-1 levels, as well as on body mass index and fasting glucose, triglycerides, total and LDL cholesterol, and C-reactive protein levels, were more pronounced among those who started the study with worse numbers.

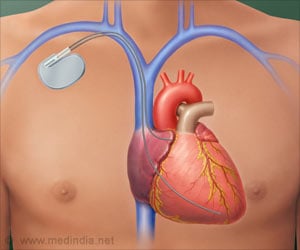

Restores Insulin Producing beta cells

Longo recently published a mouse study in Cell that may begin to explain the process, at least in the pancreas. Six to 8 cycles of alternating a 4-day fasting-mimicking diet with a normal diet restored insulin-producing β cells and insulin secretion in diabetic mice, reducing their fasting blood glucose levels to almost normal levels.

Increased expression of certain protein markers suggested that mice on the diet had greater numbers of pancreatic progenitor cells, which resulted in the generation of fully functional β cells. Longo believes that post-fasting stem cell activation drives the health and longevity benefits of his diet.

“During the refeeding, the stem cells are turned on and … they rebuild the cells and systems and organs that have been reduced in size and cell number during the fasting,” he said. The possibility of a nonsurgical, nonmedical therapy could be life changing for patients with diabetes.

“To me the most important thing is we’re one step closer to understanding how we can translate the last hundred or something years of research on caloric restriction to actually get it to the clinic in an efficient way,” de Cabo said.

Need For Further Studies

Despite the exciting findings in diabetic mice and humans with prediabetic markers, Longo cautioned that the meal plan isn’t ready for use in patients being treated for type 1 or type 2 diabetes because combining a fasting-mimicking diet with blood glucose-lowering drugs could cause hypoglycemia.

Based on promising results in mouse models of multiple sclerosis and humans with the disease, Longo also wants to test the diet in patients with autoimmune disorders. Pending positive findings, he believes the fasting-mimicking diet could become the first food-based disease treatment to gain approval from the US Food and Drug Administration.

As with any diet, the question of adherence looms large—and assumptions may not turn out to be truths. Ravussin recently worked on a weight-loss study comparing alternate-day fasting with daily caloric restriction. Surprisingly, there was a higher percentage of dropouts in the fasting group.

But for now, the success of Longo’s pioneering studies is likely to trigger more trials of dietary interventions linked to caloric restriction. “This is just the beginning,” Verdin said.

Reference

- Eric Ravussin et al., A 2-Year Randomized Controlled Trial of Human Caloric Restriction: Feasibility and Effects on Predictors of Health Span and Longevity, JAMA, (2017), doi:10.1001/jama.2017.6648.

Source-Medindia