Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that travel longer distances, adversely impact human health and ecosystems and are known to persist in the atmosphere.

- Organic aerosol forms a protective shield around pollutants like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), preventing its degradation.

- This OA shielding varies with temperature and humidity and allows PAHs to travel longer distances, across oceans.

- This has quadrupled the estimate of global lung cancer risk caused by PAHs.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are pollutants from fossil fuel burning, forest fires and biofuel consumption.

They adversely impact human health and ecosystems and are known to persist in the atmosphere. Several PAHs have been identified as cancer-causing agents by the Environmental Protection Agency in the U.S.

Despite their wide-spread presence, the mechanisms by which they persist is not well understood.

The temperature and humidity-dependent variations in the viscosity of organic aerosol (OA) prevent chemical degradation of PAHs.

"We developed and implemented new modeling approaches based on laboratory measurements to include shielding of toxics by organic aerosols, in a global climate model that resulted in large improvements of model predictions," said PNNL climate scientist and lead author Manish Shrivastava.

Globe-trotting Pollutants

To understand the traveling of aerosol shielded PAHs, the researchers compared the new model's numbers to PAH concentrations measured by Oregon State University scientists at the top of Mount Bachelor in the central Oregon Cascade Range.

"Our team found that the predictions with the new shielded models of PAHs came in at concentrations similar to what we measured on the mountain," said Staci Simonich, a toxicologist and chemist in the College of Agricultural Sciences and College of Science at OSU.

"The level of PAHs we measured on Mount Bachelor was four times higher than previous models had predicted, and there's evidence the aerosols came all the way from the other side of the Pacific Ocean."

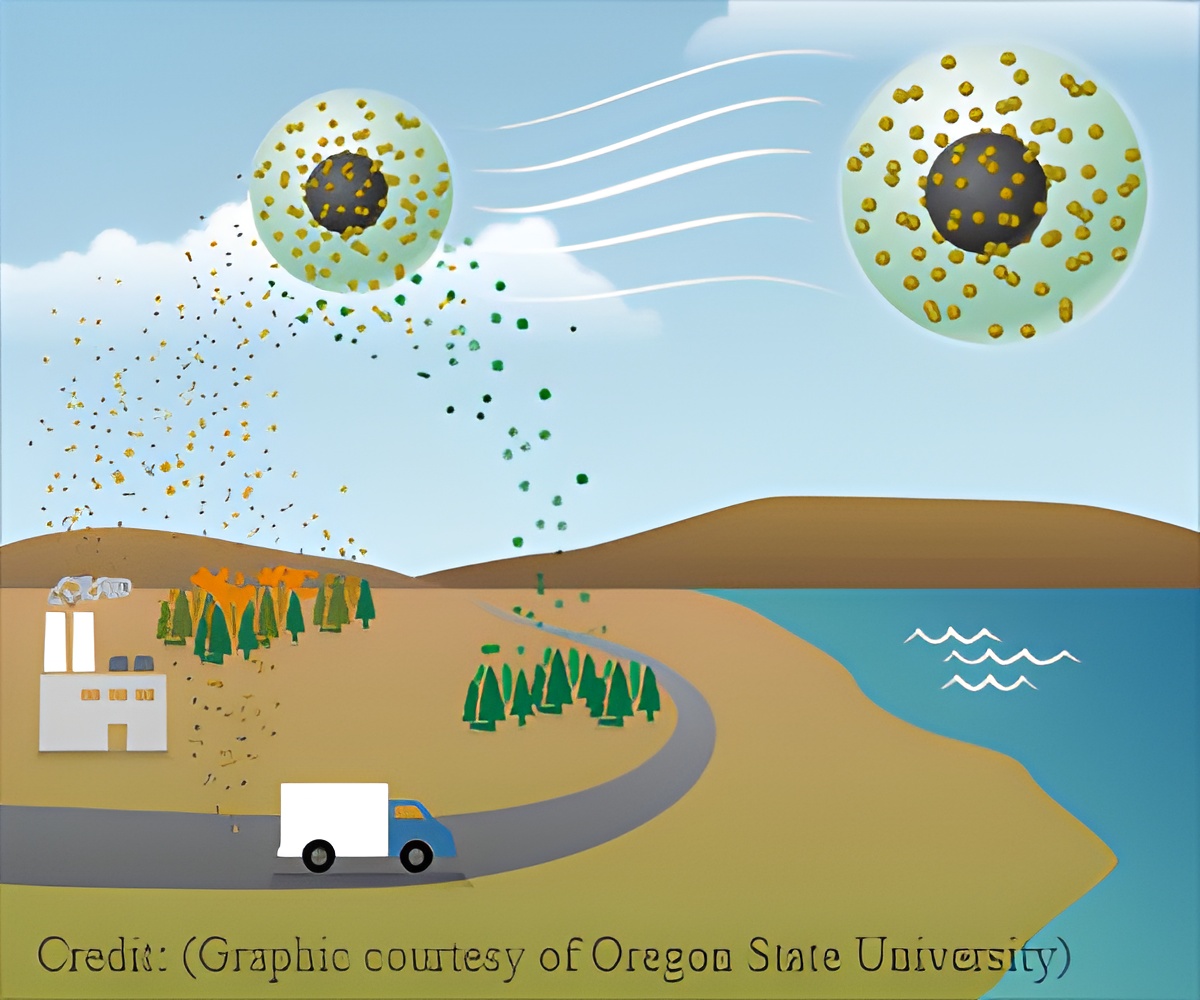

Aerosols are tiny balls of gases, pollutants, and other molecules that coalesce around the core. Many of the molecules that coat the core are known as organics. They arise from living matter such as vegetation, leaves and branches.

Pollutant such as PAHs also stick to the aerosol.

Previously researchers thought that PAHs could move freely within the organic coating of an aerosol allowing it to travel to the surface where it could be broken down by ozone.

But recent experiments led by coauthor Alla Zelenyuk show that the aerosol coatings can be quite viscous depending on the temperature and humidity condition.

If the atmosphere is cool and dry, the coating can become as viscous as tar, trapping PAHs and other chemicals. By preventing their movement, the viscous coating shields the PAHs from degradation.

On studying one of the most carcinogenic PAHs, benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), researchers found that it is efficiently bound to and transported with atmospheric particles.

Laboratory measurements show that particle-bound BaP degrades in a few hours by heterogeneous reaction with ozone, yet field observations indicate BaP persists much longer in the atmosphere.

The coatings of viscous organic aerosol (OA) causes the shielding of Bap from oxidation.

Scientists found that the shielded PAHs traveled across oceans and continents.

OA coating is more effective in shielding BaP in the middle/high latitudes compared with the tropics because of differences in OA properties.

Scientists found that the shielded PAHs traveled across oceans and continents.

As the aerosols traversed the warm and humid tropics, ozone could get access to the PAHs and oxidize them.

Cancer Risk

To look at the impact globe-trotting PAHs might have on human health, Shrivastava combined a global climate model, with a lifetime cancer risk assessment model developed by coauthors Huizhong Shen and Shu Tao, both then at Peking University.

While the previous model predicted half a cancer death out of every 100,000 people, which is half the limit outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO) for PAH exposure, the new model showed that shielded PAHs actually travel great distances, increasing the global cancer risk by four times or two cancer deaths per 100,000 people, which exceeds WHO standards.

The WHO standards were not exceeded everywhere. It was higher in China and India and lower in the United States and Western Europe.

"We don't know what implications more PAH oxidation products over the tropics have for future human or environmental health risk assessments," said Shrivastava.

"We need to better understand how the shielding of PAHs varies with the complexity of aerosol composition, atmospheric chemical aging of aerosols, temperature and relative humidity. I was initially surprised to see so much oxidation over the tropics." Shrivastava added.

The study was done by scientists at Oregon State University, the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, or PNNL, and Peking University. The research was primarily supported by PNNL.

The findings are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Reference

- Manish Shrivastava et al. Global long-range transport and lung cancer risk from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons shielded by coatings of organic aerosol. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences ; (2017) doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618475114

Source-Medindia