Beta cells in the pancreas that lack the protein renalase provoke a diminished response from immune system. The survive the autoimmune killing which may guard against type 1 diabetes. An existing drug boosts survival for insulin-producing cells under autoimmune attack.

Highlights

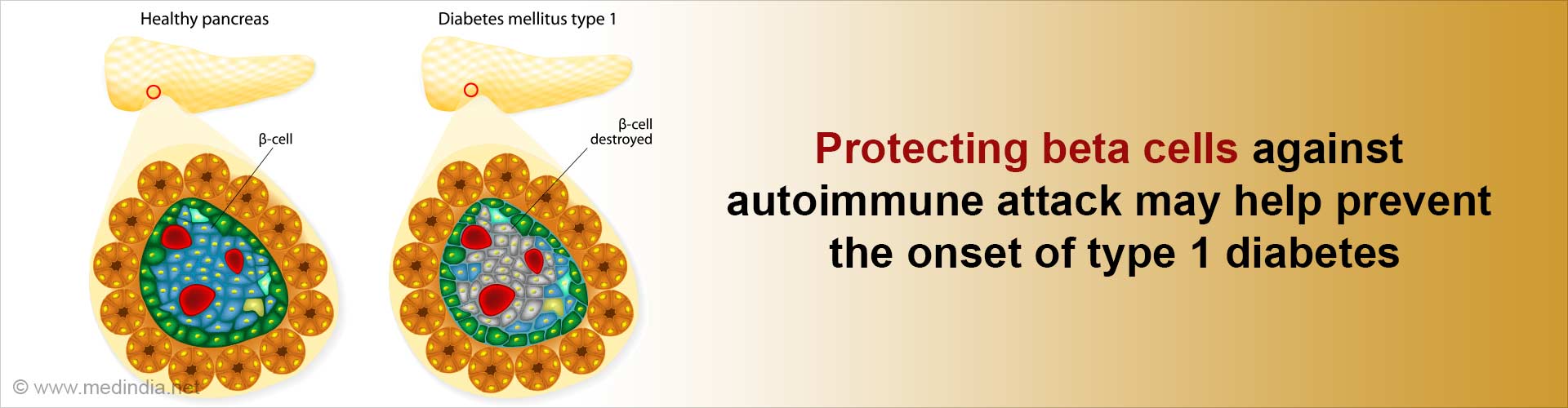

- Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease, where the body's immunity destroys the insulin-producing beta cells

- Beta cells contain a protein called renalase that makes them more functionally prone to becoming a target of the immune system

- Targeting renalase therapeutically, makes beta cells resistant to autoimmune attack, protects them against stress, and helps preserve them

Read More..

Stephan Kissler, an investigator in Joslin's Section on Immunobiology, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and co-senior author on a paper describing the work in Nature Metabolism states that targeting renalase, a protein, can protect beta cells against body’s immune attack by strengthening them against stress.

An existing FDA-approved drug, pargyline, inhibits renalase and increases the beta-cell survival in lab models.

The functional problems with beta cells themselves may trigger the autoimmune attack in type 1 diabetes, say Kissler and Yi, who is an assistant investigator in the Islet Cell and Regenerative Biology Section. "You might have genes that make the beta-cell a little bit dysfunctional and more prone to becoming a target of the immune system," Kissler explains.

A beta cell line from a non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse that mimics type 1 diabetes was used for the study. The researchers then tried to inhibit the genes across the beta-cell genome, one at a time, using a screening technique based on the CRISPR gene-editing method. Inhibiting the genes led to the deletion of the protein renalase which made the beta-cells resistant to autoimmune attack.

The CRISPR screen for surviving beta cells produced the gene for renalase, which previous research had shown is associated with type 1 diabetes.

"This was a very black-and-white research model," Kissler comments. "If the cells aren't protected, they're gone.".

Response from T immune cells spreaheaded the autoimmune attack on beta cells, and the study showed that one type of T cell was less likely to attack the renalase knock out cells compared to normal beta cells.

The researchers also saw that the renalase mutation was protecting mouse beta-cells against a condition called endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress.

To replicate the study in human cells, the team joined with Douglas Melton of the Harvard Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology to create human beta cells for similar tests in a dish "Again, we saw that the renalase knockout protected cells against ER stress," Kissler says.

Pargyline, a drug approved by the Food & Drug Administration almost 60 years ago, is used to treat hypertension. This drug is found to have an inhibitory effect on renalase.

On testing pargyline in their mouse transplant model, the Joslin researchers found that the drug protected beta cells extremely well also against ER stress. In experiments with human cells, pargyline also displayed a protective effect.

In the next step, researchers hope to test pargyline in a pilot clinical trial to see if it slows the progress of new-onset type 1 diabetes in a small number of patients.

"Since it's FDA-approved and the drug is safe, this would be the best approach to test if the protection we observed in mice and human cells will hold true in people," Kissler remarks.

Source-Medindia