A new form of hemoglobin, produced by the red blood cells after researchers altered key biological events in the cells, could form the basis of new therapies for sickle cell disease.

Blobel and colleagues, including Wulan Deng, Ph.D., formerly a member of the Blobel laboratory, and current lab member Jeremy W. Rupon, M.D., Ph.D., published their findings online today in Cell.

Key to the researcher's strategy is a developmental transition that normally occurs in the blood of newborns. A biological switch regulates a changeover from fetal hemoglobin to adult hemoglobin as it begins to silence the genes that produce fetal hemoglobin. This has major consequences for patients with the mutation that causes sickle cell disease (SCD).

Fetal hemoglobin is not affected by this mutation. But as adult hemoglobin starts to predominate, patients with the SCD mutation begin to experience painful, sometimes life-threatening disease symptoms as misshapen red blood cells disrupt normal circulation, clog blood vessels and damage organs.

Hematologists have long known that sickle cell patients with elevated levels of fetal hemoglobin compared to adult hemoglobin have a milder form of the disease. "This observation has been a major driver in the field to understand the molecular basis of the mechanisms that control the biological switch, with the ultimate goal to reverse it," said Blobel.

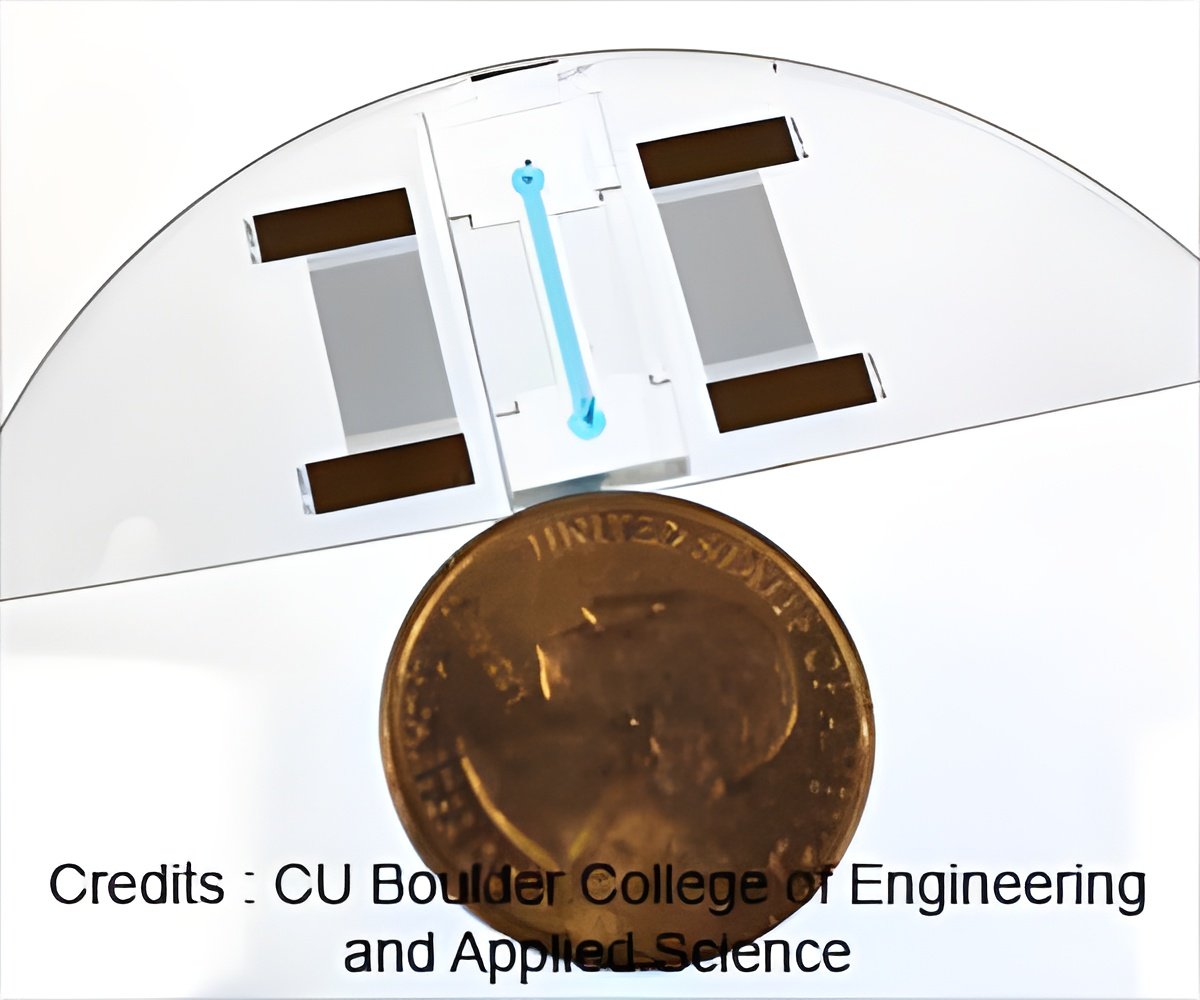

In previous research, Blobel's team used bioengineering techniques to adapt zinc-finger proteins to latch onto specific DNA sites far apart on a chromosome. The chromatin loop that results transmits regulatory signals for specific genes.

Advertisement

The next step, said Blobel, is to apply this proof-of-concept technique to preclinical models, by testing the approach in animals genetically engineered to have manifestations of SCD similar to that found in human patients. If this strategy corrects the disease in animals, it may set the stage to move to human trials.

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert