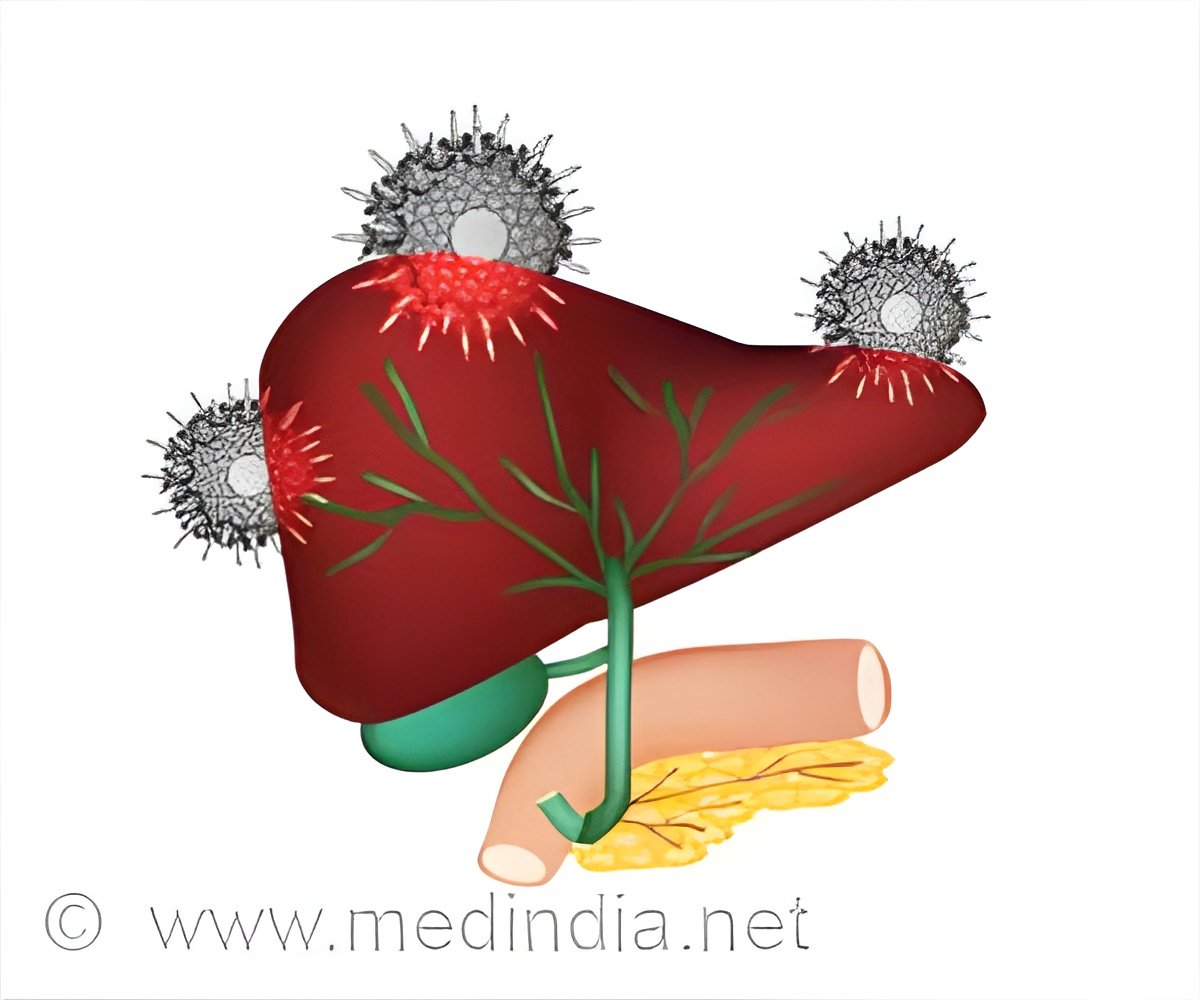

New approach that exploits the vulnerabilities in the whole life cycle of the hepatitis B virus may give hope for finding new drugs to treat hepatitis B infection.

Finding the Dark Spot in Studying Hepatitis B Virus

Hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses both attack the liver, eventually causing deadly cirrhosis or cancer. But while antivirals can cure 95 percent of HCV infections, its cousin HBV has long eluded effective therapeutics. As a result, nearly 1 million people die from HBV every year.‘Interrupting the life cycle of the hepatitis B virus may prevent its replication and spread to new cells, which could be a potential target for new drugs.’

Despite sharing an affinity for the liver, HBV and HCV are quite different. They have different genetic compositions—HBV is a DNA virus, while HCV is an RNA virus—and HBV is only about one-third the size of HCV, with a unique genetic architecture that makes it more challenging to study.But they do share some characteristics. They’re both easily transmittable and hard to shake once an infection has taken root. Some 296 million people live with a chronic HBV infection that is often asymptomatic until liver disease has advanced so far that it is largely untreatable.

Unlike with HCV, current HBV therapies can cause intolerable side effects or have limited impact, leading to lifelong drug therapy. And while there’s an effective vaccine that can block new HBV infections, it’s helpless against existing ones.

Progress has been slow for a few reasons. One is that HBV is notoriously difficult to culture in the lab. Another is that methods commonly used to study HBV in the lab are plagued by background noise from HBV DNA and plasmids. The result is a lot of genetic fuzziness that makes it hard to see the virus’s properties.

On the Road to Potential Cure for Hepatitis B

Scientists have tried workarounds to tackle this problem, but researchers hit on a winning idea: spark the virus’s life cycle later in the process using RNA, which might allow them to avoid all the DNA noise.Like other viruses, HBV hijacks a cell’s molecular machinery to reproduce, but its process is a bit unusual. Once inside the nucleus, it uses that machinery to first transcribe its DNA to RNA and then converts that into a new viral genome called covalently closed circular DNA.

Advertisement

Thanks to HBV’s tiny size, it has few RNA transcripts involved in the replication process. One turned out to be key: pre-genomic RNA. Previous research had shown that pgRNA was able to instigate replication in a relative of HBV that infects ducks.

As they continued to exploit this strategy, they used a computational method called deep mutational scanning to look for HBV mutations that confer resistance to antivirals. They’ve already found several, some of which have been detected in infected patients, but never before in deliberately grown cell cultures.

Source-Eurekalert