A new study investigates the neuroanatomical and cognitive basis of post-stroke reading and language deficits, which could help in deficit prediction in stroke survivors and suggest targeted treatments.

‘Focusing on specific reading problems in stroke survivors may help clinicians develop therapies and new clinical tests.’

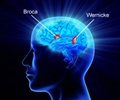

A new research focus was on phonological processing, which is understanding and being able to use the sounds that comprise language.The findings are published in Brain Communications.There are three principal aspects to this processing: auditory, or the ability to recognize the sounds of words; motor, which is the ability to produce accurate and clear speech; and auditory-motor translation, which is the translation of sounds heard into speech.

There are two broad ways that people read words: one involves sounding out words, which is particularly important for reading new words; the other involves whole-word recognition. People with post-stroke language impairment frequently have specific trouble sounding out words.

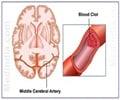

Researchers tested reading and phonological abilities in 67 people, 30 of whom had had a stroke and 37 that had not. Advanced MRI techniques allowed the researchers to trace out white matter connections, as well as map out stroke locations in the brains of affected study participants.

They found two different patterns of reading problems. Strokes involving the left frontal lobe caused problems with motor phonology and sounding out words. In contrast, strokes involving the left temporal and parietal lobes caused problems with auditory-motor translation and both ways of reading. These results are an important step forward in revealing the mechanisms of translating print to sound, which is crucial for developing rehabilitative therapies for patients who have had strokes.

Advertisement

Advertisement