Scientists have demonstrated how mouse embryonic stem cells can be used to generate self-organized, pituitary-like tissues, in an animal study.

New work by Hidetaka Suga of the Division of Human Stem Cell Technology, Yoshiki Sasai, Group Director of the Laboratory for Organogenesis and Neurogenesis, and others has unlocked the most recent achievement in self-organized tissue differentiation, steering mouse ESCs to give rise to tissue closely resembling the hormone-secreting component of the pituitary, known as the adenohypophysis, in vitro. Conducted in collaboration with Yutaka Oiso at the Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, this work was published in Nature.

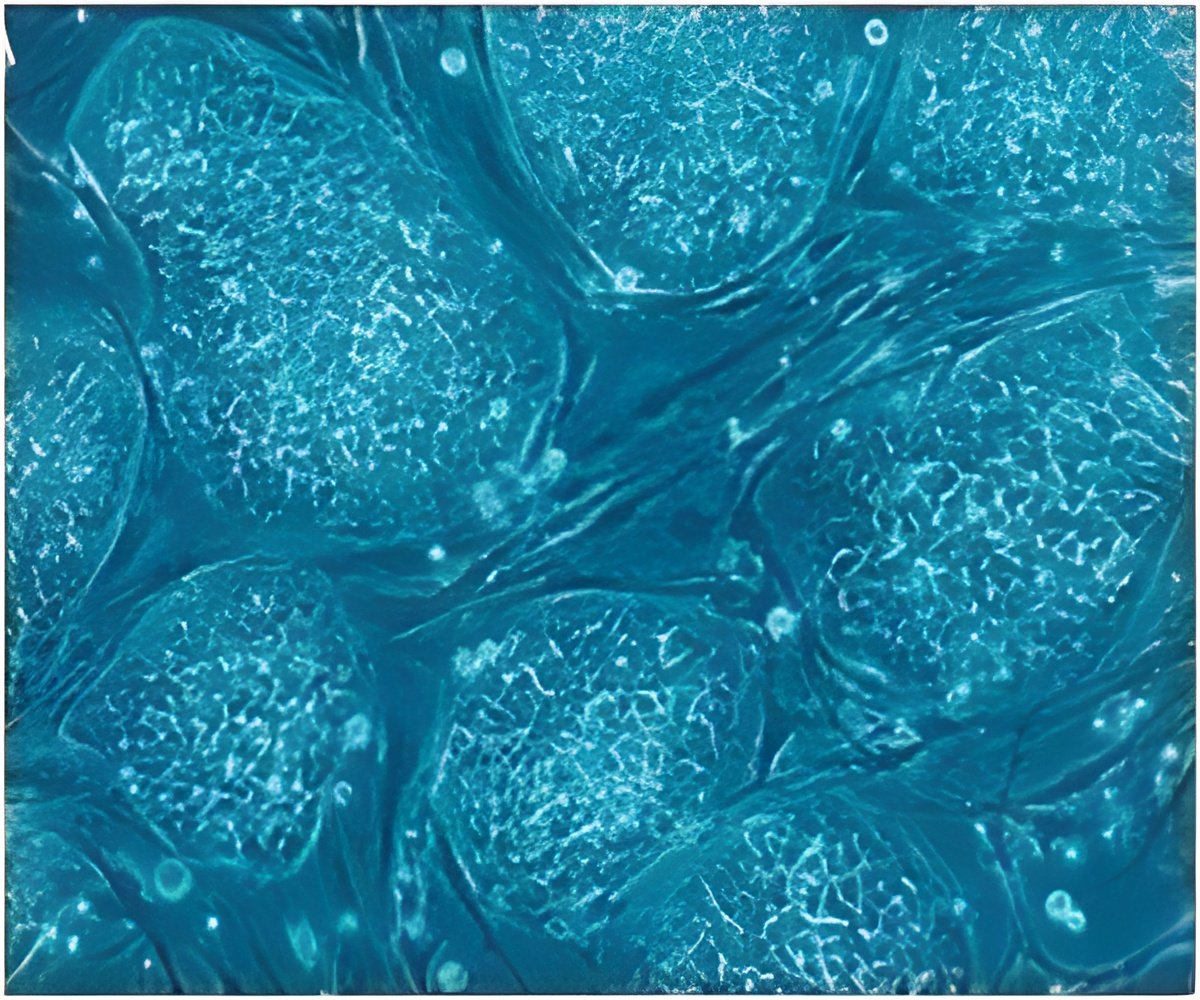

The Sasai group has complied an impressive list of achievements in induced differentiation using an ES cell culture technique dubbed SFEBq (shorthand for "serum-free floating culture of embryoid body-like aggregates with quick re-aggregation"), including high-efficiency methods for the differentiation of dopaminergic, cerebral cortex, cerebellar Purkinje, and other neuronal cell types. In recent years, refinements of this approach have enabled the first tantalizing insights into the developmental capacity of pluripotent stem cells, showing their ability to give rise to multi-cell-type populations of cortical and retinal neurons that spontaneously self-organize into stratified tissue nearly identical to that of the developing embryo.

In the group's most recent work, Suga sought to use SFEBq to derive the secretory component of the pituitary (hypophysis) from mouse ES cells. In embryonic development, the pituitary emerges from a region of the non-neural (rostral) head ectoderm, adjacent to the anterior neural plate. Guided by molecular interactions, this placodal region forms an indentation, known as Rathke's pouch, in the developmental predecessor of the roof of the mouth, and eventually gives rise to the anterior section of the pituitary, the source of hormones involved in growth, reproduction and modulating the physiological response to stress.

The Sasai lab had previously reported how a modified version of the SFEBq approach lacking extrinsic growth factors could spur ES cells to give rise to hypothalamic neurons. Building on this finding, Suga found by further tweaking the conditions he could steer populations of such stem cells to differentiate simultaneously into the neighboring rostral head ectoderm and hypothalamic neuroectoderm, both of which are required to development of the adenohypophysis. Interestingly, the cells in these clusters spontaneously organized into distinct layers resembling those of the corresponding embryonic tissues. This effect appears to be attributable to the increase of BMP signaling in larger cell aggregates, leading to differentiation into non-neural ectoderm. To test whether co-culture of this ectoderm with hypothalamic tissue would lead to the formation of Rathke's pouch-like structures, Suga observed the ESC-derived aggregates for nearly two weeks, and found that by adding the signaling factor Sonic hedgehog, he was able to induce the self-directed formation of this vesicular tissue.

The next important test was whether this in vitro anterior pituitary anlage would show similar functionality to the physiological activity of the adenohypophysis. Of the many critically important pituitary hormones, they chose adenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) for their first assay. Previous research had suggested that Notch signaling interferes with the development of ACTH-secreting cells, so the group added a Notch blocker to the culture medium and found that this triggered the generation of such cells at high efficiencies. Following a similar principle, they showed that by adding Wnt, glucocorticoid and insulin to the culture at appropriate doses and stages, they could obtain growth hormone-secreting cells in quantity. By varying the recipe of the growth factor cocktail, they were able to induce other pituitary hormones as well. And, critically, the group was able to show that in vitro hormone secretion could respond to requisite signals and engage in regulatory feedback just as in the body.

Advertisement

Yoshiki Sasai, leader of the study, commented on this most recent demonstration of the remarkable self-organizing capabilities of embryonic stem cells in vitro. "We have previously shown how ES cells can give rise to self-organized, three-dimensional neuronal and sensory tissues, and in this report we describe for the first time how this principle can be used to generate to an endocrine tissue, suggesting our approach is of general applicability. Suga, himself an endocrinologist, remarks, "We currently treat pituitary deficiencies by hormone replacement, but achieving the correct dosage is not a straightforward problem, given the naturally fluctuating levels secreted within the body. I am hopeful that this new finding will lead to further advances in regenerative medicine in the endocrine system."

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert