Advanced prostate cancer and high blood cholesterol have long been known to be connected, but it has been a chicken-or-egg problem.

‘A cellular process that cancer cells hijack to hoard cholesterol and fuel their growth has been identified by researchers.’

The findings are published online this month in the journal Cancer Research.Donald McDonnell, chairman of the Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology at Duke, said, "All cells need cholesterol to grow, and too much of it can stimulate uncontrolled growth. Prostate cancer cells somehow bypass the cellular control switch that regulates the levels of cholesterol allowing them to accumulate this fat. This process has not been well understood. In this study, we show how prostate cancer cells accomplish this."

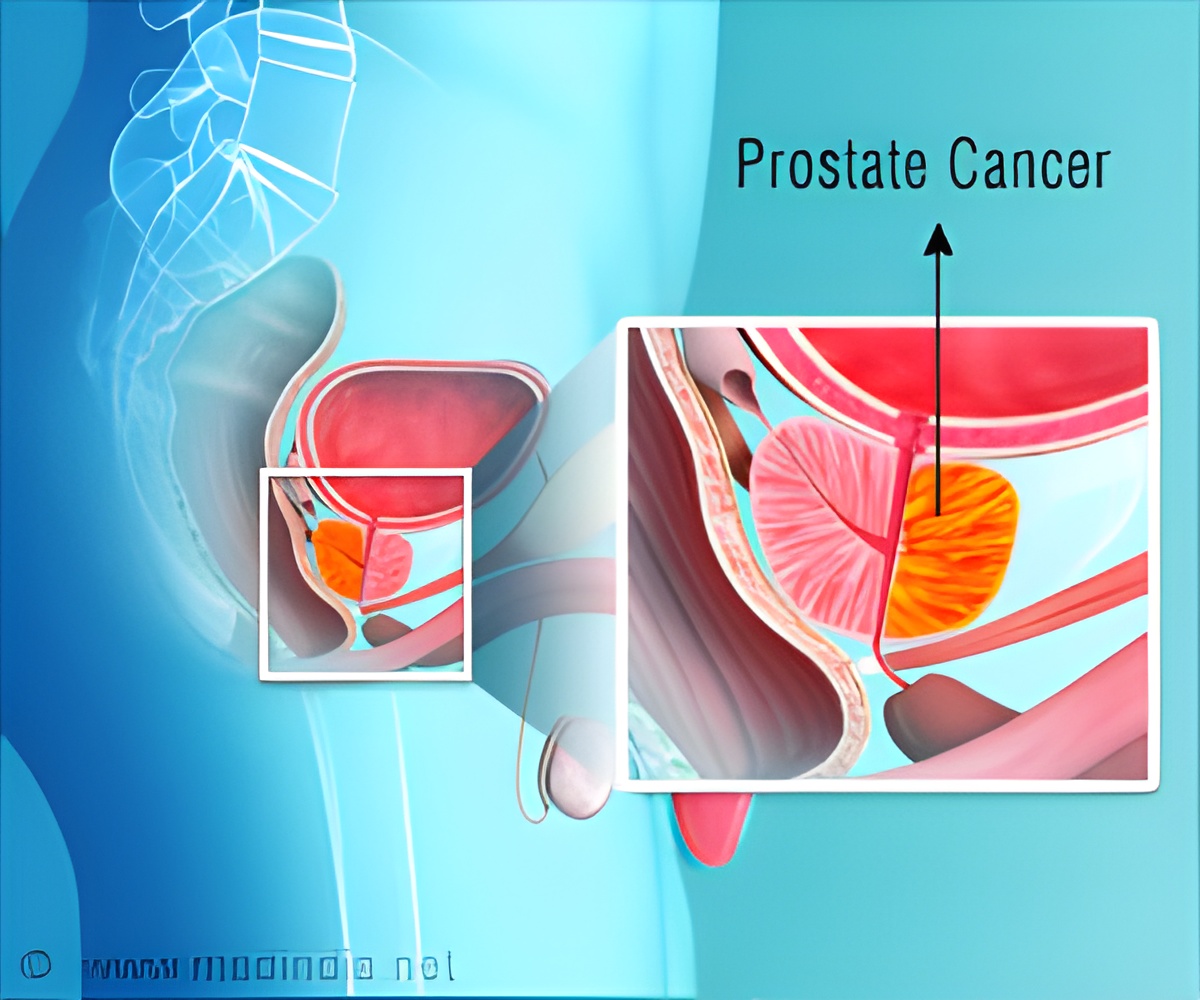

McDonnell and colleagues began by identifying genes involved in cholesterol regulation in prostate tumors. They homed in on a specific gene, CYP27A1, which is a key component of the machinery that governs the level of cholesterol within cells.

In patients with prostate cancer, the expression of the CYP27A1 gene in tumors is significantly lower, and this is especially true for men with aggressive cancers compared to the tumors in men with more benign disease. Downregulation of this gene basically shuts off the sensor that cells use to gauge when they have taken up enough cholesterol. This in turn allows accumulation of this fat in tumor cells. Access to more cholesterol gives prostate cancer cells a selective growth advantage.

"It remains to be determined how this regulatory activity can be restored and/or whether it's possible to mitigate the effects of the increased cholesterol uptake that result from the loss of CYP27A1 expression," McDonnell said.

Advertisement

McDonnell said is lab is continuing the research, including finding ways to induce cells to eject cholesterol, reverse the inhibition of CYP27A1 activity, or introduce compounds that interfere with cholesterol-production in the tumor.

Advertisement