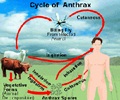

Scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences have uncovered how the body''s immune system launches , Anthrax

The researchers discovered that the fight against invading anthrax bacteria begins with the first infected cell. They found that initially impacted macrophages immediately communicate with other immune cells to sound the alarm and develop a survival strategy. Remarkably, the key signaling molecule involved in the survival response is adenosine triphosphate or ATP, a basic currency of energy transfer used by all organisms.

"The warning alarm sounded during anthrax infection is elegant, complex and can be effective in slowing spread of the pathogen," said Michael Karin, PhD, distinguished professor of pharmacology and senior author of the study.

Karin explained that ATP is released from macrophages infected and poisoned with anthrax toxins through a special channel in the cell membrane. This ATP is then sensed by a receptor on a second macrophage, which assembles and activates a complex of molecules known as the inflammasome. The inflammasome then releases into the bloodstream an immune-activating molecule known as interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta), which alerts macrophages throughout the body to mobilize and increase their resistance to anthrax-induced cell death.

Researchers confirmed the importance of this complex signal transduction pathway in fighting anthrax in a series of experiments using genetically altered mice or inhibitor drugs. Whenever the researchers interfered with the ATP channel, the ATP receptor, inflammasome proteins or the IL-1beta molecule, they found that the macrophages could not survive, anthrax bacteria grew unchecked or the infected mouse died rapidly. They also noted that the immune response pathway responded only to the most dangerous bacterial pathogens. Infections using a mutant anthrax bacterium lacking the deadly toxins did not set off the alarm system in test animals.

"We hope these findings can be exploited for the design of new treatments to help the body combat serious bacterial pathogens," said Victor Nizet, MD, professor of pediatrics and pharmacy, whose infectious disease research laboratory contributed to the study. "Supporting the survival of macrophages and preserving their immune function may buy patients precious time until antibiotic therapy is brought on board to clear the infection."

Advertisement