Elderly patients with impaired mental function were more than twice as likely to be dead one year after their heart attack as those with healthy mental function.

‘Assessing mental status is a simple way to identify elderly patients at particularly high risk of poor outcomes following a heart attack.’

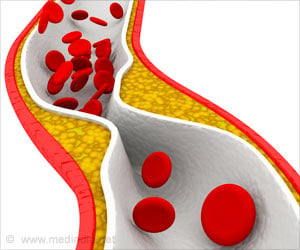

"Patients with reduced mental status can then receive more intensive management such as regular follow-up appointments with their general practitioners or nurses, more specific assessment for an early diagnosis of dementia and tailored therapy," said study author Professor Farzin Beygui of Caen University Hospital, France. The risks of dementia, Alzheimer's disease, confusion and delirium increase with age. Elderly people are also at higher risk of having a heart attack and dying afterwards. People aged 75 and over account for approximately a third of heart attack admissions and more than half of those dying in hospital after admission for a heart attack. Until now it was not known whether impaired mental status affects the prognosis of elderly heart attack patients.

This study assessed the impact of mental status on the risk of death in 600 patients aged 75 and above consecutively admitted for heart attack and followed-up for at least one year. Mental status was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) - both simple bedside tests routinely used in clinical practice.

Cognitive impairment was detected in 174 (29%) patients. The association was independent of other potential predictors of death such as age, sex, invasive treatment, type of myocardial infarction, heart failure, and severity of the heart attack.

Impaired mental status was also associated with a nearly four-fold higher rate of bleeding complications while in hospital and a more than two-fold higher risk of being readmitted to hospital for cardiovascular causes within three months after discharge.

Advertisement

He concluded: "Identifying these patients may help us target treatment to those who need it most."

Advertisement