Although atrial fibrillation isn't life-threatening, it is still a serious medical condition. Use of anticoagulation therapies help reduce stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation.

‘More than 33 million people worldwide have atrial fibrillation, which is a leading cause of stroke. Increasing the use of anticoagulation therapies has the potential to prevent hundreds of thousands of strokes.’

This corresponds to a more than three-fold increase in anticoagulation use from baseline to one year in the intervention group, compared with the control group. The increased drug use was accompanied by a modest, but notable, reduction in the risk of stroke. "More than 33 million people worldwide have atrial fibrillation, which is a leading cause of stroke," said principal investigator Prof Christopher Granger, professor of medicine at Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, US.

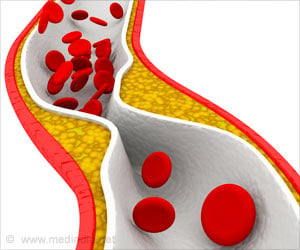

"Only about half of patients with atrial fibrillation take anticoagulant drugs, despite these medications being highly effective in preventing strokes," he continued. "Increasing the use of anticoagulation therapies has the potential to prevent hundreds of thousands of strokes each year."

The IMPACT-AF trial2 assessed whether education of providers and patients with atrial fibrillation, with monitoring and feedback, could increase the use of oral anticoagulation compared to usual care. The trial included 2 281 patients with atrial fibrillation from 48 centres in Argentina, Brazil, China, India and Romania. In each country, centres were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive an educational intervention (intervention group) or usual care (control group) for one year.

The educational intervention was customised to each country and explained the benefits of anticoagulant therapies, as well as the risks and costs. Patients were given brochures and shown videos, and then monitored at doctor visits to get their feedback and learn of any problems that kept them from staying on the medication. Physicians received information and reports from the researchers through emails, articles, webinars and podcasts. The primary outcome was the change in the proportion of patients treated with oral anticoagulation at one year.

Advertisement

Prof Granger said: "The trial shows that education and monitoring are effective ways to improve adherence to oral anticoagulation medication in patients with atrial fibrillation. If this intervention was broadly applied, which we believe is possible, the public health implications could be substantial."

Advertisement

"We observed a reduction in strokes in the intervention compared to the control group," said Prof Dragos Vinereanu, professor of cardiology at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Bucharest, Romania and the principal investigator for Romania. "Stroke reduction is the ultimate goal, and this finding shows the potential benefit of improving anticoagulation care."

Prof Granger pointed out that a limitation of the cluster randomisation design, in which centres (rather than individual patients) are assigned to the intervention or control arm, was that baseline use of anticoagulants may have been overestimated in the control sites.

He concluded: "Additional studies are needed to better understand why such a large proportion of patients with atrial fibrillation discontinue, or never even start, oral anticoagulation therapy."

Source-Eurekalert