Research published in BMJ Open reveals that girls born unexpectedly small or underweight seem to be twice as likely to have fertility problems in adulthood.

But as this is the first research of its kind, further studies will be needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn, they caution.

The researchers base their findings on 1206 women who were born in Sweden from 1973 onwards, and part of a straight couple seeking help for fertility problems at one major centre between 2005 and 2010.

The primary cause of infertility—female, combined, male or unexplained—was gleaned from the patients' medical records, while details of their birth size, age, and weight were gathered from Sweden's national medical birth register.

Infertility was attributed to female causes in 38.5% of the cases; male causes in just under 27%; combined causes in just under 7%; and unexplained in 28%.

Around two thirds of the women were of a healthy weight, while around one in four was overweight. One in 20 was obese while almost 2.5% were under weight.

Advertisement

Just under 4% of the women had been born prematurely; a similar proportion were underweight at birth; while just under 6% were unexpectedly small babies.

Advertisement

Similarly, these women were almost three times as likely to have been born unexpectedly small as those whose primary cause of infertility was unexplained.

These findings held true even after influential factors, including previous motherhood and current weight, were taken into account.

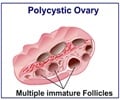

By way of possible explanation, the authors suggest that growth restriction in the womb might affect the developing reproductive organs as previous research has linked fetal growth restriction with reduced ovulation.

And other research has pointed to the fetal origins of some adult diseases, they add.

They caution that the sample size was relatively small and carried out in one geographical area in one country so may not be applicable elsewhere. Further research would be needed before definitive conclusions could be drawn, they say.

But they say that if the associations between low birthweight or small birth size and infertility are confirmed, this may have implications for the prevalence of infertility problems.

"As medical research and care advances, more infants will be born [with low birthweight or small size] and survive, which in turn might influence future need of infertility treatment," they conclude.

Source-Eurekalert