A team of American and Canadian scientists have developed a new anthrax inhibitor that blocks the host receptors where anthrax toxin attaches in the body.

A team of American and Canadian scientists from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., and the University of Toronto have developed a new anthrax inhibitor that blocks the host receptors where anthrax toxin attaches in the body.

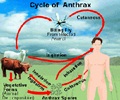

The researchers said that the inhibitor was able to bind to multiple sites on the host receptor making it much for potent than the inhibitors that binds to single site. The researchers found that the new approach led to a 50,000-fold increase in activity to block multiple binding sites when compared with a more conventional inhibitor. They found that all six rats that got these inhibitors were protected against the toxins and had no adverse effects.Anthrax is a serious disease caused by bacteria, Bacillus anthracis, which can affect both human and animals. The B. anthracis when inhaled, as when used as a biological weapon, is much more serious and can be fatal despite treatment with antibiotics. Most therapies including antibiotics used to treat anthrax are targeted against the bacteria or the toxin released by the bacteria that damages the host organism.

However, these bacteria can become resistant to antibiotics over time, and resistance can also be engineered intentionally into a germ as when used as a biological weapon. Also, the antibiotic used only slows the progression of infection, but do not counter the effects of the toxins once an infection takes hold.

However, the use of anthrax inhibitor could help address this issue as they block the receptor sites used by the bacteria to gain a lethal foothold in the body and thus can help reduce the number of deaths caused by inhaled anthrax once it is fully developed. According to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, inhaled anthrax still has a fatality rate of 75 percent even after antibiotics are given.

Ravi Kane, an associate professor of chemical and biological engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., and the co-author of the study said "combining the inhibitor with antibiotic therapy may increase the likelihood of survival for an infected person." He said that instead of trying to constantly match evolutionary changes in bacteria and viruses blocking the host receptors was a better approach for treatment.

The researchers said that the same approach could be used to design blocking agents to protect against other diseases including SARS, flu and AIDS.

Advertisement

Source-Medindia

SAR