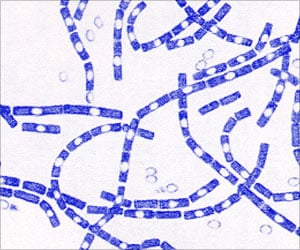

The Inuit harbor a composition and diversity of gut microbes remarkably similar to their urbanized, westernized counterparts in urban Montreal.

‘Dietary fiber is a major factor driving the overall composition of the gut microbiome, suggested a new study.’

Researchers at the University of Montreal, in Canada, have

characterized the gut microbiome of the Canadian Arctic Inuit for the

first time. Reporting this week in mSphere, an open-access

journal of the American Society for Microbiology, the researchers found

that the Inuit harbor a composition and diversity of gut microbes

remarkably similar to their urbanized, westernized counterparts in urban

Montreal. What differences they did find were subtle, and in the

relative abundances of individual taxa. The strong similarities between the Inuit and western microbiomes surprised Jesse Shapiro, a computational evolutionary biologist at the University of Montreal, who led the analysis. His team hypothesized that they'd find greater microbial diversity in the Inuit study population.

"We expected to see a big difference based on what has been seen in other isolated traditional populations who eat a traditional diet," he said.

The findings on the Inuit from Shapiro and his collaborators strongly diverge from that trend. What a person eats helps determine the microbial population that inhabits their gut. The hunter-gatherer communities in South America and Africa at the focus of previous studies eat traditional diets that are high in fiber.

The Inuit, on the other hand, don't. The Inuit who participated in the study live in the Hamlet of Resolute Bay, a remote Arctic village with only about 300 inhabitants. Their traditional diet includes raw game (such as caribou, seal, whale and fish) and few plant-derived foods. It's low in carbohydrates, rich in animal fats and proteins, and a rich source of vitamins and minerals.

Advertisement

The researchers used 16s rRNA sequencing to characterize the microbial population in stool samples donated by 19 inhabitants of the Hamlet of Resolute Bay, a Canadian Arctic village on the southern end of Cornwallis Island accessible only by plane (and, when the sea ice breaks up, by boat). Shapiro and his team compared the Inuit gut microbiomes to those in samples from 26 adults in Montreal.

Advertisement

"Our study points to dietary fiber as a major factor driving the overall composition of the microbiome," says Shapiro.

Shapiro and his colleagues say a number of factors might contribute to the similarity between the Inuit and Western microbiomes. For example, as the Inuit diet becomes more westernized, the population faces a rising prevalence of obesity - which has been linked to less microbial diversity. The effect might also have to do with seasonality. The Inuit diet changes through the year, and the samples were collected in the late summer, when the Inuit eat a mix of traditional foods and those purchased from a supermarket. Shapiro says that collecting samples during other times of the year, when the traditional diet dominates, might yield different results.

He sees the study as the first step - but definitely not the last - toward understanding how the Inuit microbiome and relates to their diet. "Other communities could be quite different," Shapiro says. "This is a snapshot at one point in time, of one community, at one time point."

Source-Eurekalert