Understanding the mechanisms that turn sets of genes on or off is a fundamental quest in biology, and one that has clinical importance in diseases like cancer, where gene control goes awry.

‘The stable nucleosome array leads to a chromatin architecture that is refractory to further remodeling required for ubiquitinated-H2A target gene activation.’

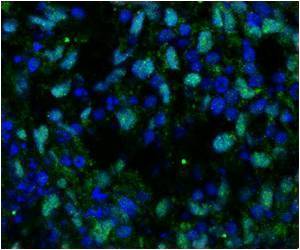

University of Alabama at Birmingham researcher Hengbin Wang, Ph.D., and colleagues have identified one such mechanism. In a paper published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Wang and colleagues describe a key role for a protein called RSF1 in silencing genes. Besides the molecular biology details, the researchers also showed that disruption of RSF1 expression in the embryos of African clawed frogs caused severe developmental defects in the tadpoles through a dysregulation of mesodermal cell fate specification.

RSF1 acts on chromatin, the organized structure of the chromosome where the 6-foot-long DNA of each human cell is highly condensed by wrapping around spools of histone proteins. Chromatin is not static, however it is highly dynamic and changes in its structure to control different physiological processes.

One contributor to chromatin fluidity is modifications of the histone proteins made by adding or removing chemical groups to the histone tails. The histones can be modified by acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, ubiquitination or ADP-ribosylation.

In his current work, Wang, an associate professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics in the UAB School of Medicine, focused on the addition of ubiquitin to the histone subunit H2A. This prevalent modification is linked to gene silencing, and removal of ubiquitin from H2A leads to gene activation. Wang and colleagues discovered that RSF1 mediates the gene-silencing function of ubiquitinated-H2A.

Advertisement

In human and mouse cells, the genes regulated by RSF1 were found to overlap significantly with those controlled by part of a complex that ubiquitinates H2A. Knockout of RSF1 in cells derepressed the genes regulated by RSF1, and this was accompanied by changes in ubiquitinated-H2A chromatin organization and release of linker histone H1.

Advertisement

"RSF1 binds to ubiquitinated-H2A nucleosomes to establish and maintain the stable ubiquitinated-H2A nucleosome pattern at promoter regions," they wrote.

"The stable nucleosome array leads to a chromatin architecture that is refractory to further remodeling required for ubiquitinated-H2A target gene activation. When RSF1 is knocked out, ubiquitinated-H2A nucleosome patterns are disturbed and nucleosomes become less stable, despite the presence of ubiquitinated-H2A. These ubiquitinated-H2A nucleosomes are subjected to chromatin remodeling for gene activation."

Wang says knowledge of the ubiquitinated-H2A binding site may help in the discovery of other ubiquitinated histone-binding proteins.

Source-Eurekalert