Chromosomal instability could make cancer aggressive, according to scientists at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

‘Certain molecules destroy the warning signals before they reach neighboring immune cells. This is why some tumors wont respond to immunotherapy.’

Read More..

"The elephant in the room is that we didn't really understand how cancer cells were able to survive and thrive in this inflammatory environment," says Samuel Bakhoum, a physician-scientist at MSK and a member of the Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program.Read More..

According to a new study from Dr. Bakhoum's lab, the reason is that a molecule sitting on the outside of the cancer cells that destroys the warning signals before they ever reach neighboring immune cells.

The findings help to explain why some tumors do not respond to immunotherapy, and -- equally important -- suggest ways to sensitize them to immunotherapy.

Detecting Dangerous DNA

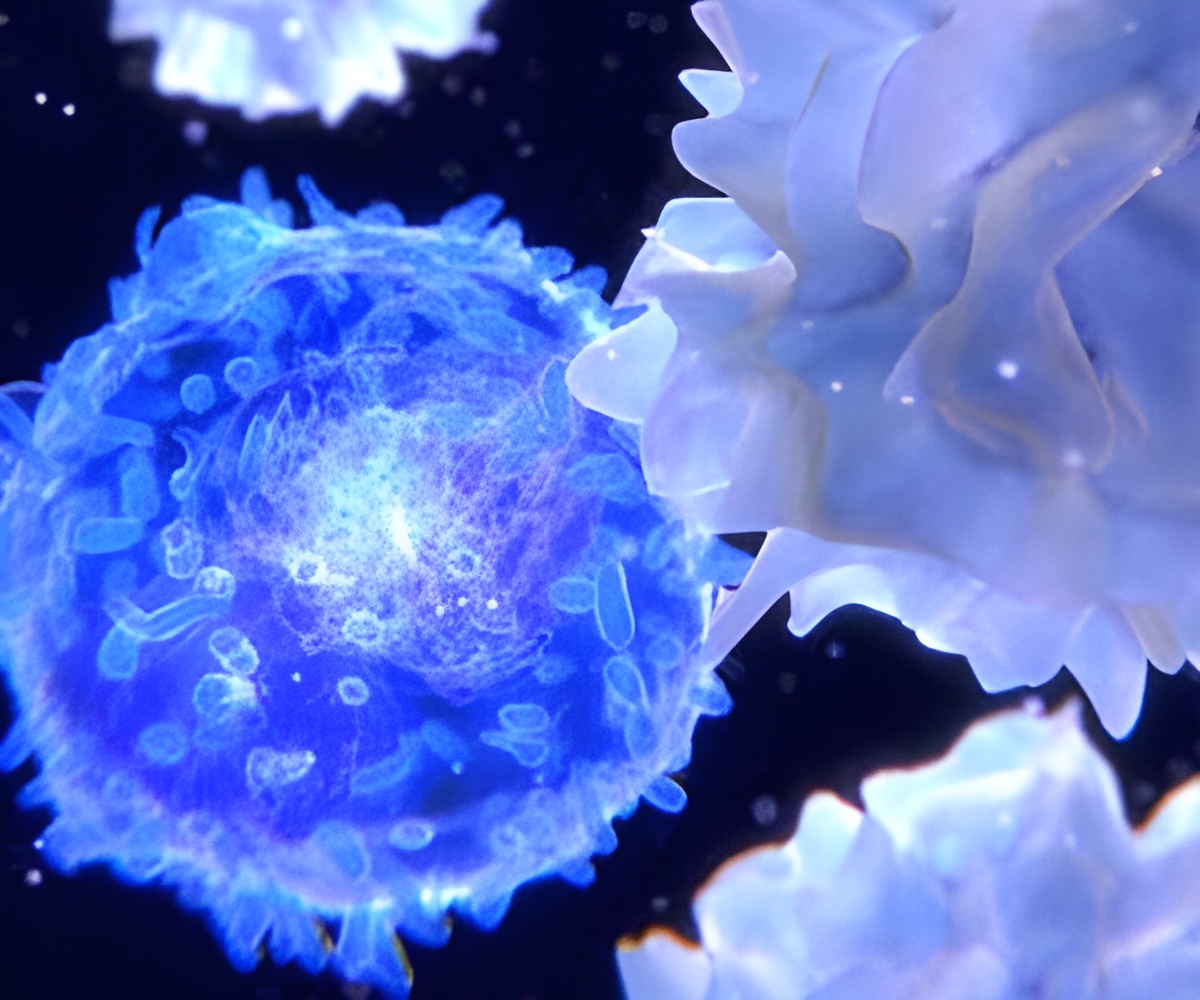

The warning system Dr. Bakhoum studies is called cGAS-STING. When DNA from a virus (or an unstable cancer chromosome) lands in a cell's cytoplasm, cGAS binds to it, forming a compound molecule called cGAMP, which serves as a warning signal. Inside the cell, this warning signal activates an immune response called STING, which addresses the immediate problem of a potential viral invader.

Advertisement

Previous work from the Bakhoum lab had shown that cGAS-STING signaling inside of cancer cells causes them to adopt features of immune cells -- in particular, the capacity to crawl and migrate -- which aids their ability to metastasize.

Advertisement

Examples of human triple negative breast cancer staining negative (left) and positive (right) for ENPP1 expression. Examples of human triple negative breast cancer staining negative (left) and positive (right) for ENPP1.

The scissor-like protein that coats cancer cells is called ENPP1. When cGAMP finds its way outside the cell, ENPP1 chops it up and prevents the signal from reaching immune cells. At the same time, this chopping releases an immune-suppressing molecule called adenosine, which also quells inflammation.

Through a battery of experiments conducted in mouse models of breast, lung, and colorectal cancers, Dr. Bakhoum and his colleagues showed that ENPP1 acts like a control switch for immune suppression and metastasis. Turning it on suppresses immune responses and increases metastasis; turning it off enables immune responses and reduces metastasis.

The scientists also looked at ENPP1 in samples of human cancers. ENPP1 expression correlated with both increased metastasis and resistance to immunotherapy.

Empowering Immunotherapy

From a treatment perspective, perhaps the most notable finding of the study is that flipping the ENPP1 switch off could increase the sensitivity of several different cancer types to immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors. The researchers showed that this approach was effective in mouse models of cancer.

Several companies -- including one that Dr. Bakhoum and colleagues founded -- are now developing drugs to inhibit ENPP1 on cancer cells.

Dr. Bakhoum says it's fortunate that ENPP1 is located on the surface of cancer cells since this makes it an easier target for drugs designed to block it.

It's also relatively specific. Since most other tissues in a healthy individual are not inflamed, drugs targeting ENPP1 primarily affect cancer.

Finally, targeting ENPP1 undercuts cancer in two separate ways: "You're simultaneously increasing cGAMP levels outside the cancer cells, which activates STING in neighboring immune cells, while you're also preventing the production of the immune-suppressive adenosine. So, you're hitting two birds with one stone," Dr. Bakhoum explains.

The pace of the research has been incredibly fast, he says. "One of the things I would be really proud of is if this research ends up helping patients soon, given that we only just started this work in 2018."

He hopes there will be a phase I clinical trial of ENPP1 inhibitors within a year.

Source-Eurekalert