A new study has found that people with changes in the small blood vessels in their eyes are more likely to later suffer a stroke than people without these signs.

The eyes are, since ages, regarded as a mirror of the inner self. However, according to a new study, eyes may now predict the likelihood of a stroke and stroke-related death.

The study, published in the October issue of Neurology, describes a novel simple, non-invasive diagnostic tool using the eyes to determine whether people have a higher risk of suffering from a stroke. According to the study, people who have tiny lesions on the back of the eye are two to three times more likely to suffer a stroke or stroke-related death, independent of other risk factors.In a study of more than 3,600 Australians aged 49 and older, researchers found that those with damage to eye blood vessels were 70 % more likely to have a stroke during a follow-up period than those who did not have such damage. The researchers followed participants for seven years, noting which ones had strokes or transient ischemic attacks, or mini-strokes, caused by blocked blood vessels.

Special photographs of the retina of the eyes of the participants were taken and examined for changes suggestive of small blood vessel damage, or retinopathy. These small vessel changes can be seen in the early stages of the condition, well before eyesight is affected.

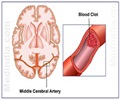

The blood vessels in the eye share similar anatomical characteristics and other characteristics with the blood vessels in the brain. The signs of damage included tiny bulges in blood vessels, called microaneurysms, and hemorrhages, tiny blood spots where the bulging vessels have leaked into surrounding eye tissue, but usually don't affect eyesight in the short run.

The study concludes on the note that this test is a marker for stroke even for people who don't have other stroke risk factors like high blood pressure. Usually about 2 % of people above the age of 50 will have a stroke, but the researchers found that about 5 to 6 % of people who had retinal lesions had a stroke within six or seven years. However, the authors add that more research needs to be done to confirm these results, but they say it is exciting to think that this fairly simple procedure could help us predict whether someone will be more likely to have a stroke several years later.