Little-understood protein previously implicated in a rare genetic disorder plays an unexpected and critical role in building and maintaining healthy cells, Italian and U.

Little-understood protein previously implicated in a rare genetic disorder plays an unexpected and critical role in building and maintaining healthy cells, Italian and U.S. biologists report in the journal Nature.

The protein, called "atlastin," does its work by fusing intracellular membranes in a previously undocumented way, the researchers claim."If you'd asked me a year ago whether this was possible, I would have said, 'No,'" said study co-author James McNew, associate professor of biochemistry and cell biology at Rice University.

"In fact, that's exactly what I told (co-author) Andrea Daga when we first spoke about the idea a year ago," he added.

To reach the conclusion, McNew spent past 15 years studying SNARE proteins, a specialized family of proteins that carries out membrane fusion. It's a vital process that happens thousands of times a second in every cell of our bodies.

"It is fitting that the discovery of a new protein capable of fusing membranes comes 10 years after the demonstration that SNAREs can fuse lipid bilayers," said Daga, a researcher at the Eugenio Medea Scientific Institute in Conegliano, Italy.

In the new study, Daga's and McNew's research teams used fruit flies to study how atlastin functions. The atlastin in fruit flies is very similar to the human version of the protein and serves the same function.

Advertisement

"Atlastin is the third, and it's the only one that requires enzymatic activity, so it's distinctly different," he added.

Advertisement

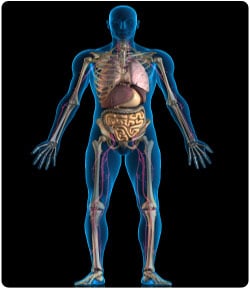

The tests showed that cells with extra atlastin had an overdeveloped endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a system of interconnected membrane tubes and chambers that's critical for normal cell function. The tests also showed too little atlastin led to a fragmented ER. Flies with defective atlastin were sterile and short-lived.

"The endoplasmic reticulum is an ever-changing environment," McNew said.

"It grows. It retracts. It expands. It collapses. It's highly dynamic, and for that to be the case, there has to be a mechanism by which it can grow new pieces and connect those pieces together. That's where the fusion comes in," he added.

Daga said: "We hope the findings lead to a better understanding of hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), the genetic disorder that atlastin has been linked with."

HSP, a rare genetic condition, is marked by a partial paralysis of the lower extremities due to defects in the body's longest cells, the neurons that run from the spine through the legs.

Source-ANI

SRM