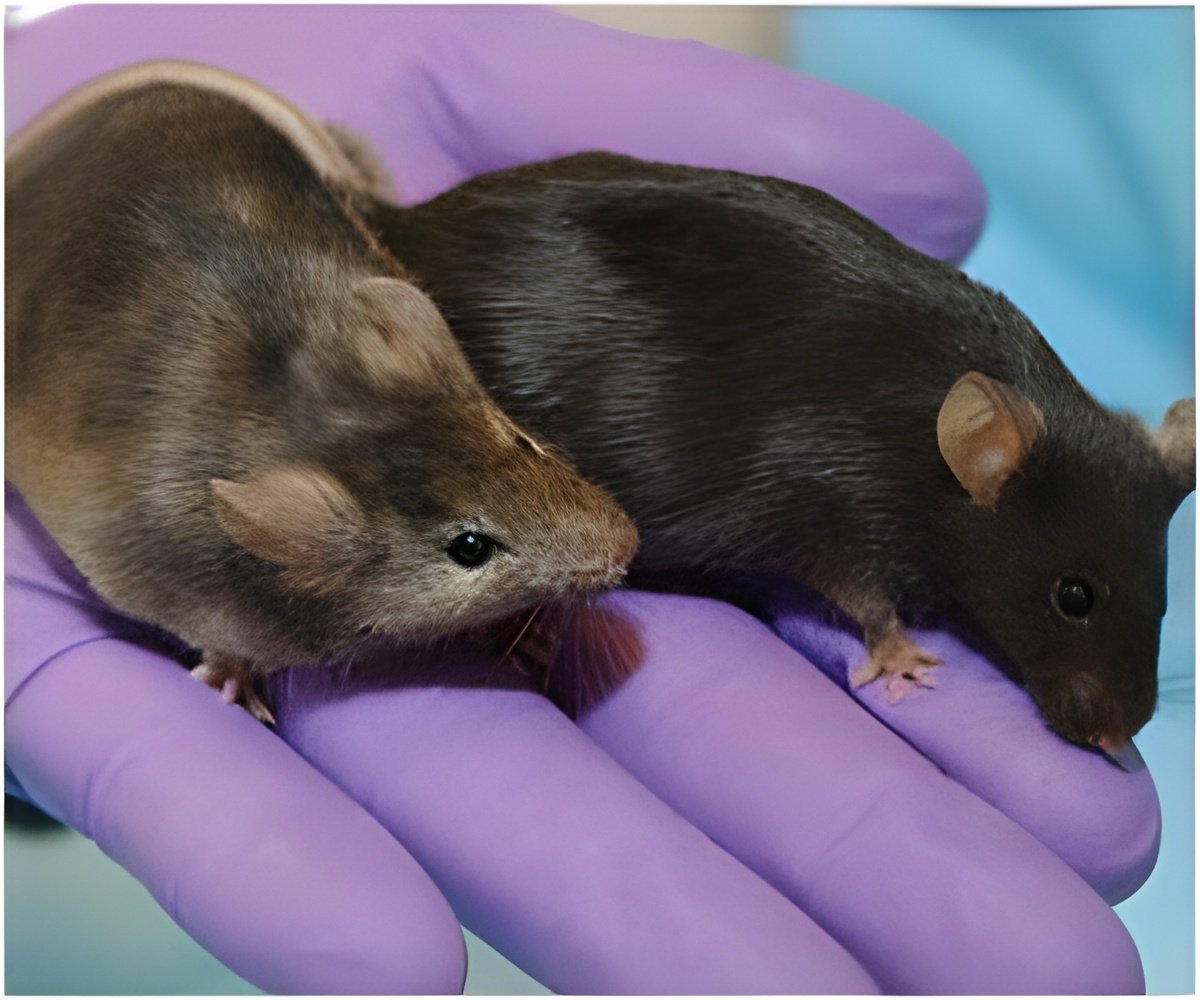

Female mice whose growth was restricted in the womb had lower birth weights, were less active later in their lives, and were at a greater risk of suffering from obesity, a new study found

"These findings were a bit of a surprise," said Waterland, corresponding author of the report.

He had already shown that genetically normal female offspring of obese female mice of a specific type (prone to obesity and marked with a yellow coat) were themselves prone to obesity and inactivity. However, he realized he also had data on the mice's weight at birth. The birth weight data showed that the offspring of these overweight females were growth restricted in the uterus.

This was surprising because babies born to obese human women tend to be larger at birth, although there is a slightly elevated risk of low birth weight as well, said Waterland. When he looked at historical reports of people who had been born in famine conditions, he found that women – but not men – who had been growth-restricted in early life were more likely to be obese.

These included women born during the Dutch Hunger Winter near the end of World War II, the great famine in China from 1959 to 1961 and the Biafran famine during the Nigerian civil war (1967-1970).

Once it was considered important to help infants born small to "catch up and achieve a normal weight for their age," said Waterland. "Increasingly, these and other epidemiologic data show that it might not be a good thing. It might set you up for bad outcomes in the long term."

Advertisement

That could make evolutionary sense, said Waterland. In times of food scarcity, it might be more important for females to be developmentally 'programmed' to conserve their energy for future bearing of offspring.

Advertisement

Others who took part in this research include Dr. Maria S. Baker, Dr. Ge Li, and John J. Kohorst, all of BCM. Kohorst is now with the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Source-Eurekalert