The yellow fever vaccine has been genetically modified by researchers at The Rockefeller University to prime the immune system to fend off the mosquito borne parasites that cause malaria

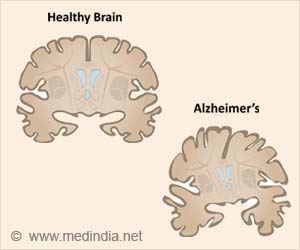

Malaria is one of the most pressing health crises of developing countries: in communities stricken by infection, attendance at work and school drops, and poverty deepens. It has been known since the 1960s that one form of the malaria parasite - called the sporozoite - can wake up the immune system and help to protect against future infection.

The only way to gather sporozoites, however, is to pluck them one-by-one from the salivary glands of irradiated, malaria-ridden mosquitoes.

To provide immunity, the attenuated parasites must then be injected in high doses - or delivered by the bites of hundreds of mosquitoes - a labor intensive approach not feasible for large-scale use.

"We needed to come up with another way to get the benefits of sporozoite immunization," said Charles M. Rice, head of the Laboratory of Virology and Infectious Disease.

Along with researchers from Michel C. Nussenzweig's Laboratory of Molecular Immunology at Rockefeller and colleagues at New York University, Rice and his team considered that fighting infection with infection might be the key.

Advertisement

Previous work in the Rice laboratory and by others had shown that this vaccine strain could be modified to include short sequences from other pathogens, including malaria.

Advertisement

The protein they chose, called CSP, covers the surface of the malaria sporozoite and is thought to be the main reason that this form of the parasite stimulates the immune system so effectively.

Immunization of mice with the YF17D-CSP vaccine led to a measurable jump in immune activity against the malaria protein, but the single shot was not enough to protect the animals from infection with the mouse form of the malaria parasite.

The group therefore added a booster shot to the vaccination regimen. Animals that had been immunized with YF17D-CSP, or with a saline solution control, were given a low dose of irradiated sporozoites.

While the saline-sporozoite group was only partially protected from challenge with viable parasites, vaccination with YF17D-CSP plus the sporozoites protected 100 percent of the animals against infection.

Cristina Stoyanov, lead author, said: "These results are exciting because they show the YF17D-CSP vaccine can prime the immune response against a malaria parasite."

Although the utility of this approach for human immunization is not yet clear, the team hopes that further studies in other animal models might eventually lead to an effective vaccine.

The findings were reported online May 6 in the journal Vaccine.

Source-ANI