The mechanism of how tumors grow resistant to radiotherapy has been identified by recent research at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research.

‘Tumor’s resistance to extended radiotherapy is caused by a molecular sensor called the STING/Type 1.’

"It has been known for some time that radiation induces inflammation, and we've shown in our earlier work that it does so through a molecular sensor found in cells known as the stimulator of interferon genes, or STING," says Ralph Weichselbaum, co-director of the Ludwig Center at Chicago, who led the study with Yang-Xin Fu of the UT Southwestern Medical Center. "However, there's a dark side to radiation: after it causes good inflammation,which mounts an immune attack on cancer cells in the irradiated tumor,it causes a bad kind of inflammation that suppresses immune responses."STING detects DNA fragments inside cells, fragments generated by the damage high energy radiation does to chromosomes. In previous studies, Weichselbaum, Fu and their colleagues showed that STING links the detection of such fragments to the production of immune factors known as type 1 interferons. These factors ultimately boost the activation of killer T cells, immune cells that attack sick and cancerous cells,and cause much of the destruction of tumors associated with radiation therapy.

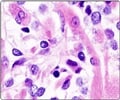

The researchers hypothesized that this same STING/Type 1 interferon signaling cascade might also account for the resistance tumors develop to extended radiotherapy. The immunosuppression, they found, is caused by an influx of particular suppressive immune cells known as monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (M-MDSCs) that are drawn into the tumor due to long-term STING/Type 1 interferon signaling.

Using mouse models of lung and colon tumors, the researchers found that the tumor-infiltrating M-MDSCs express a cell surface receptor known as CCR2, whose ligand,or binding target,is expressed by cells upon STING activation. They then showed that resistance to radiotherapy was significantly reduced in mice engineered to lack CCR2.

To determine whether the effect might be translated into clinical practice, the researchers checked whether it could be reproduced in mice that express CCR2 with the use of antibodies to the receptor. They found it could. Most notably, in both types of mice the destruction of tumors was significantly boosted when the radiation therapy was delivered along with a STING-activating drug and anti-CCR2 antibodies.

Advertisement

Pharmaceutical companies are developing STING activating drugs for cancer therapy, and one is currently being evaluated in clinical trials in combination with checkpoint blockade,a type of immunotherapy that boosts T cell attack on certain types of tumors. Similarly, antibodies to CCR2 are also being developed as potential immunotherapeutic agents. The current study lays the groundwork for combining these experimental drugs to improve the effects of radiotherapy for a variety of solid tumors.

Advertisement

The complete research is published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source-Eurekalert