A new software tool to diagnose chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE has been discovered by scientists.

‘Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease of the brain with a history of repetitive brain trauma. New MRI-based technique detects abnormal pattern of brain changes.’

While the findings from this single case report are preliminary, they raise the possibility that MRI scans could be used to diagnose CTE and related conditions in living people. At present, CTE can be diagnosed only by direct examination of the brain during an autopsy.," said Dr. David Merrill, assistant clinical professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA.

Along with its potential benefits in diagnosing patients in the clinic, the MRI scanning technique could also help speed research of CTE, helping scientists better understand its prevalence in the population and in studying potential therapies, said Dr. Cyrus A. Raji, a senior resident in radiology at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center.

Raji and Merrill are lead authors of the report, which appears online Aug. 23 in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

The case's patient, with the pseudonym "Bob Smith," is a former high school fullback who also saw action on defense and special teams, meaning he was on the field for much of entire games. During his three-year playing career Smith received hundreds of blows to the head, including at least one concussion in which he was knocked unconscious and, after regaining consciousness, jogged to the wrong sideline.

Advertisement

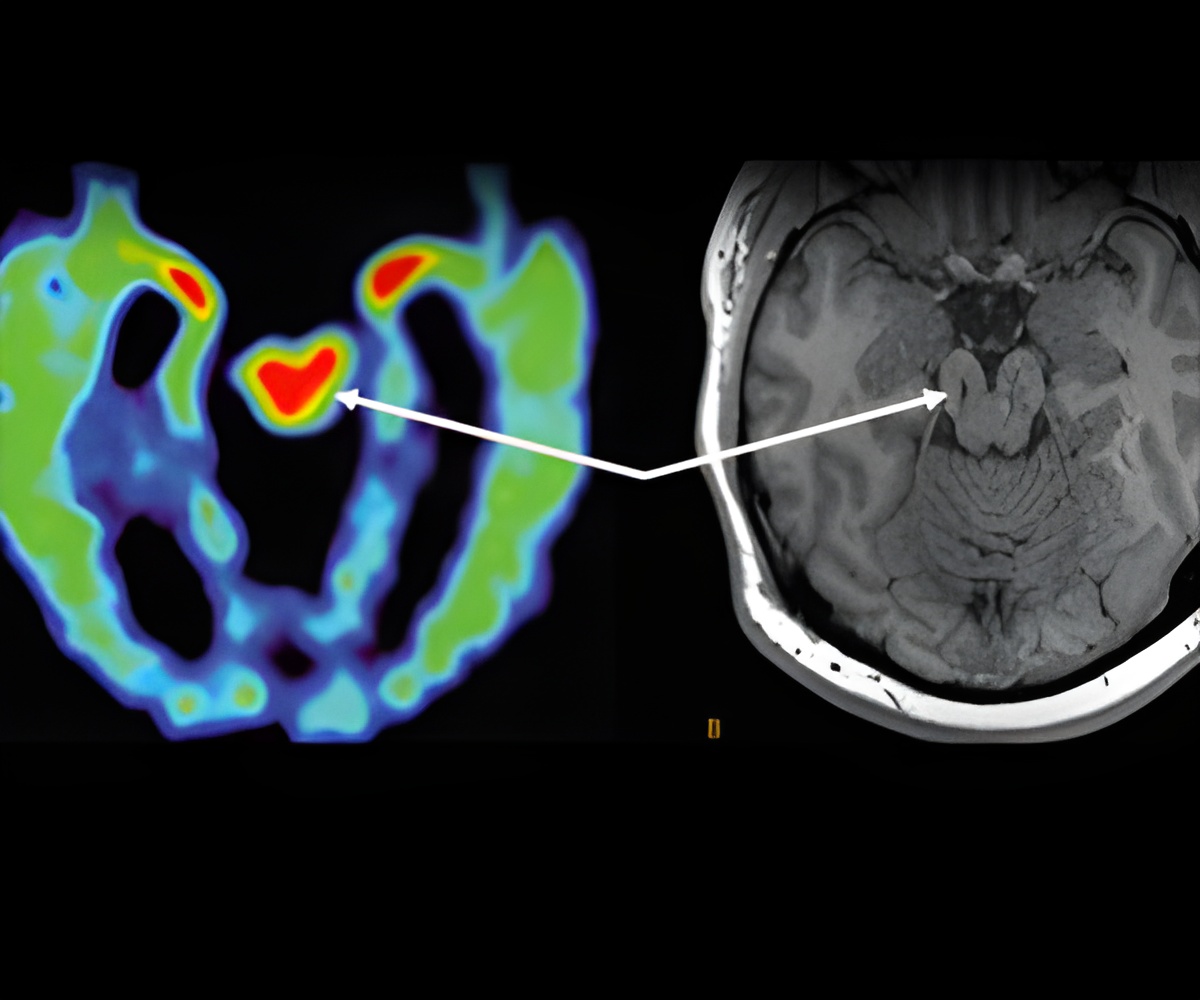

The MRI scan did reveal a few small lesions consistent with Smith's history of brain trauma. Merrill and Raji also used a new FDA-cleared MRI software analysis tool called Neuroreader to measure the volumes of 45 different regions of the patient's brain.

Advertisement

The analysis revealed abnormally low volumes for Smith's brainstem, his ventral diencephalon and frontal lobes. The shrinkage in these volumes was worse in the later scan, suggesting a progression of disease. On the whole Smith's brain lost about 14 percent of its total gray-matter volume (the volume taken up by brain cells, not nerve fibers) during the four-year interval.

"The specific areas that were abnormally low in their volumes helped us understand that this patient's cognitive symptoms were likely due to his history of traumatic brain injury," Raji said.

Researchers are trying to develop other methods for diagnosing CTE in the living, including PET scans based on radioactive tracers that bind to tau aggregates. But an MRI-based method, which uses no radioactive materials, would be safer and less expensive, Merrill said.

Merrill and colleagues now hope to do larger studies to analyze MRI data for people with histories of head trauma, which would help determine whether the technique is broadly useful in detecting CTE.

Other authors of the study included Jorge Barrio and Dr. Gary Small of UCLA; and Dr. Bennet Omalu, of UC-Davis.

Source-Eurekalert