Multiple sclerosis, which was long viewed as primarily an autoimmune disease, is not actually a disease of the immune system, says an article

Framing MS as a metabolic disorder helps to explain many puzzling aspects of the disease, particularly why it strikes women more than men and why cases are on the rise worldwide, Corthals says. She believes this new framework could help guide researchers toward new treatments and ultimately a cure for the disease.

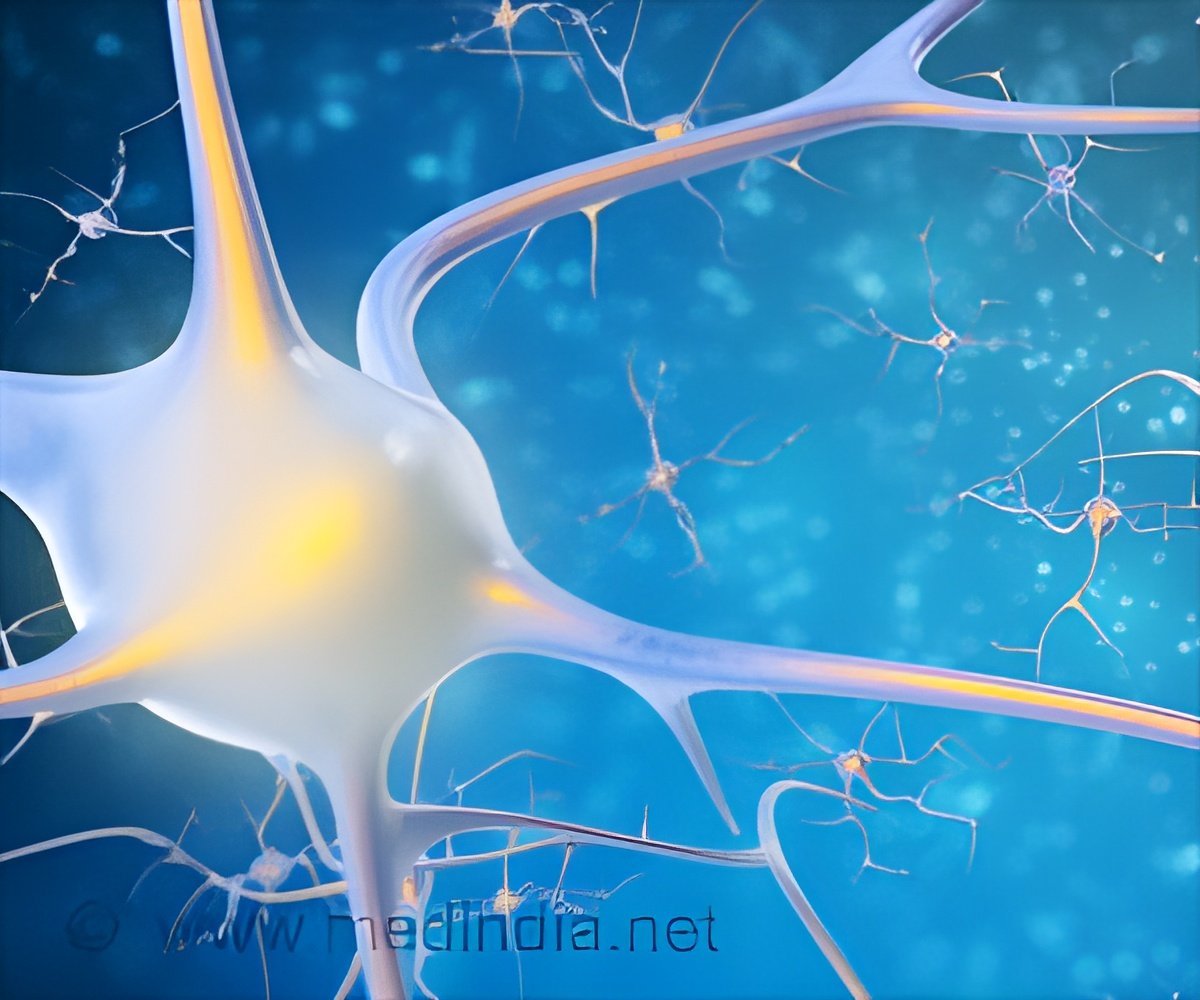

Multiple sclerosis affects at least 1.3 million people worldwide. Its main characteristic is inflammation followed by scarring of tissue called myelin, which insulates nerve tissue in the brain and spinal cord. Over time, this scarring can lead to profound neurological damage. Medical researchers have theorized that a runaway immune system is at fault, but no one has been able to fully explain what triggers the onset of the disease. Genes, diet, pathogens, and vitamin D deficiency have all been linked to MS, but evidence for these risk factors is inconsistent and even contradictory, frustrating researchers in their search for effective treatment.

"Each time a genetic risk factor has shown a significant increase in MS risk in one population, it has been found to be unimportant in another," Corthals said. "Pathogens like Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated, but there's no explanation for why genetically similar populations with similar pathogen loads have drastically different rates of disease. The search for MS triggers in the context of autoimmunity simply hasn't led to any unifying conclusions about the etiology of the disease."

However, understanding MS as metabolic rather than an autoimmune begins to bring the disease and its causes into focus.

THE LIPID HYPOTHESIS

Advertisement

"When lipid metabolism fails in the arteries, you get atherosclerosis," Corthals explains. "When it happens in the central nervous system, you get MS. But the underlying etiology is the same."

Advertisement

The lipid hypothesis also sheds light on the link between MS and vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D helps to lower LDL cholesterol, so it makes sense that a lack of vitamin D increases the likelihood of the disease—especially in the context of a diet high in fats and carbohydrates.

Corthals's framework also explains why MS is more prevalent in women.

"Men and women metabolize fats differently," Corthals said. "In men, PPAR problems are more likely to occur in vascular tissue, which is why atherosclerosis is more prevalent in men. But women metabolize fat differently in relation to their reproductive role. Disruption of lipid metabolism in women is more likely to affect the production of myelin and the central nervous system. In this way, MS is to women what atherosclerosis is to men, while excluding neither sex from developing the other disease."

In addition to high cholesterol, there are several other risk factors for reduced PPAR function, including pathogens like Epstein-Barr virus, trauma that requires massive cell repair, and certain genetic profiles. In many cases, Corthals says, having just one of these risk factors isn't enough to trigger a collapse of lipid metabolism. But more than one risk factor could cause problems. For example, a genetically weakened PPAR system on its own might not cause disease, but combining that with a pathogen or with a poor diet can cause disease. This helps to explain why different MS triggers seem to be important for some people and populations but not others.

"In the context of autoimmunity, the various risk factors for MS are frustratingly incoherent," Corthals said. "But in the context of lipid metabolism, they make perfect sense."

Much more research is necessary to fully understand the role of PPARs in MS, but Corthals hopes that this new understanding of the disease could eventually lead to new treatments and prevention measures.

"This new framework makes a cure for MS closer than ever," Corthals said.

Source-Eurekalert