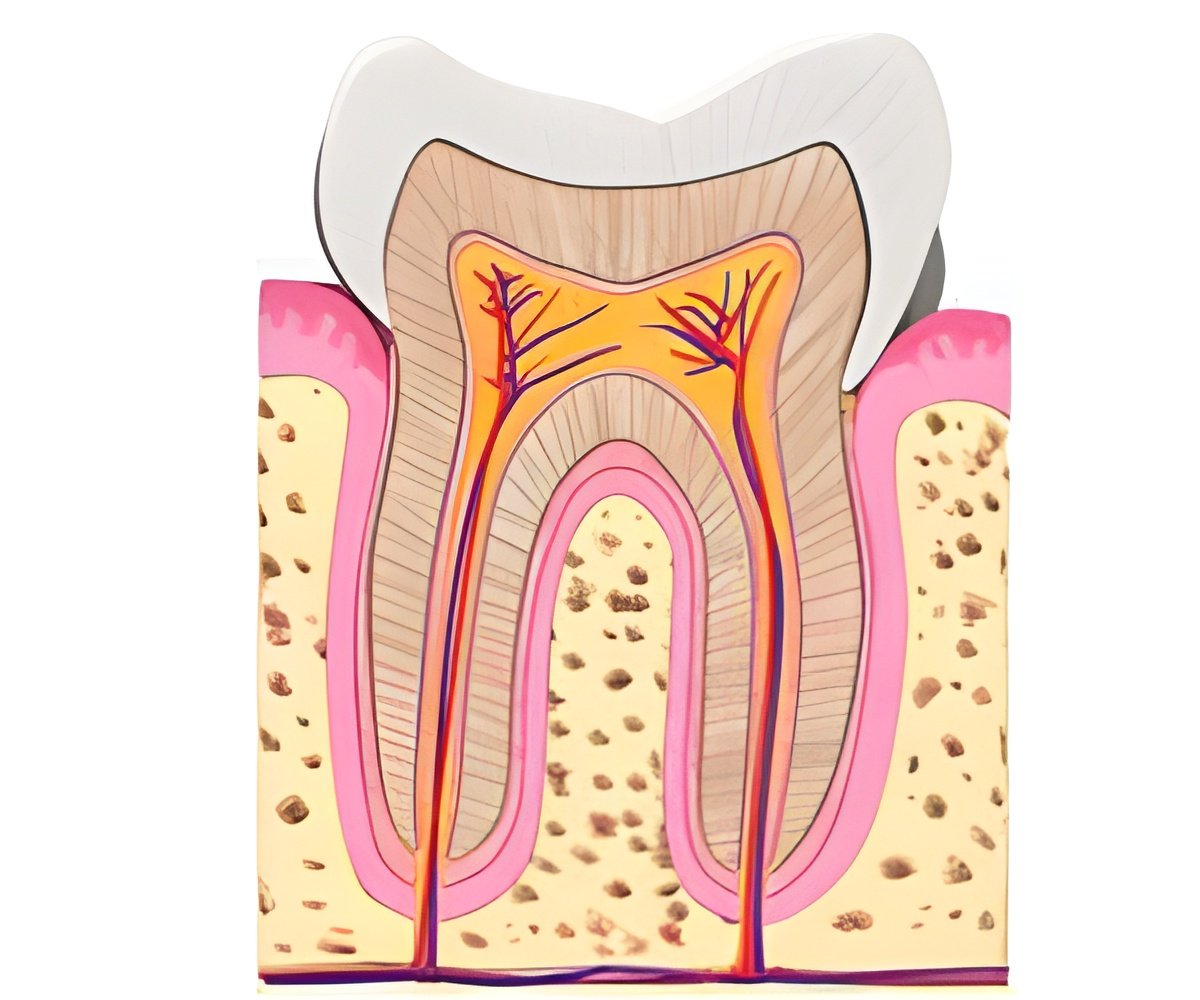

Our tooth is attached directly to the jaw bone by a special tissue known as bone of attachment which resorbs the root of our teeth enabling tooth shedding.

‘Our tooth is attached directly to the jaw bone by a special tissue known as bone of attachment which resorbs the root of our teeth enabling tooth shedding.’

In bony fish and land vertebrates, the developing tooth becomes attached directly to the jaw bone by a special tissue known as "bone of attachment", and when it is time for the tooth to be shed this attachment must be severed; specialized cells come in and resorb the dentine and bone of attachment until the tooth comes loose. That's why our milk teeth loose their roots before they are shed. But when did this process evolve? The authors of the new study decided to investigate a jaw bone of the 424 million year old fossil fish Andreolepis from Gotland in Sweden, close to the common ancestor of all living bony fish and land vertebrates.

The jaw is a tiny thing, less than a centimetre in length, but it hides a wonderful secret: the internal microstructure of the bone is perfectly preserved and contains a record of its growth history.

Until recently it has only been possible to see internal structures by physically cutting thin sections from the fossil and viewing them under the microscope, but this destroys the specimen and provides only a two-dimensional image that is hard to interpret.

However, at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, it is now possible to make tomographic scans that capture the same level of microscopic detail, in three dimensions, without damaging the specimen. Donglei Chen, first author of the study, has spent several years painstakingly 'dissecting' the scan data on the computer screen, building up a three-dimensional map of the entire sequence of tooth addition and loss - the first time an early fossil dentition has been analyzed in such detail.

Advertisement

This is the earliest known example of tooth shedding by basal resorption, and it seems to be most similar to the process of tooth replacement seen today in primitive bony fish such as gar (Lepisosteus) and bichir (Polypterus). Like in these fish, new replacement teeth developed alongside the old ones, rather than underneath them like in us.

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert