A non-injectable vaccine showed positive results when tested on monkeys. It's easy to administer and also helps avoid the problem of needle disposal.

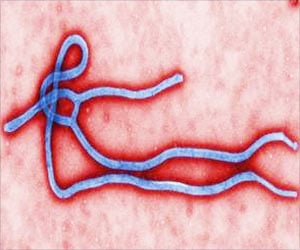

A weakened version of the virus, called parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3), was engineered to contain an Ebola virus glycoprotein in order to stimulate an immune response against Ebola. HPIV3 is a common cause of respiratory tract infections in young children.

Researchers gave the vaccine to rhesus macaques by placing a nebulizer mask over their faces, delivering the vaccine into their noses and mouths. Next, when the vaccinated animals were injected with what would normally be a lethal dose of Ebola virus, they survived.

The animals showed no ill side effects from the vaccine, known for now as HPIV3/EboGP, according to senior author Alex Bukreyev, professor of virology at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. "This study demonstrates successful aerosol vaccination against a viral hemorrhagic fever for the first time," he said.

Other Ebola vaccines are currently being tested, but they are delivered by injection. Bukreyev and colleagues compared the aerosol vaccine to an unrelated injectable vaccine, and found that although both protect macaques, they induced very different types of the immune response.

There is no vaccine on the market to prevent Ebola. More study is needed to determine which kinds of vaccines may be most effective. Ebola spread quickly across West Africa beginning in late 2013 and ballooned into the deadliest outbreak in history.

Advertisement

According to infectious disease expert Jesse Goodman, a professor of medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center, the study is "important" and "well-done." Goodman, who was not involved in the research, agreed with the study authors that an inhalable vaccine could make administering medicine easier in remote locations and in times of crisis, and could help avoid the problem of needle disposal. "For these reasons, this vaccine is a welcome addition to others currently under study," he told AFP in an email.

Advertisement

Source-AFP