Mounting research has shown that alcohol damages the developing brains of teenagers, injuring them significantly more than it does adult brains.

For as long as one can remember concerned adults have tried to limit teenage alcohol consumption. Public health experts often warn that teenage drinkers show increased risks of involvement in car accidents, and fights.

But while early drinking was blamed for time away from homework acquiring social skills, and other related tasks of growing up mounting research has shown that alcohol damages the developing brains of teenagers, injuring them significantly more than it does adult brains.These findings have lain to rest the assumption that people can drink heavily for years before significant neurological injury is caused to themselves. In addition the research has suggested that early heavy drinking may even undermine the precise neurological capacities needed to protect oneself from alcoholism.

This probably explains why people who begin drinking at an early age tend to have greater risks of becoming alcoholics. A national survey of 43,093 adults have revealed that 47 percent of those who begin drinking alcohol before the age of 14 become alcohol dependent at some time in their lives, compared with 9 percent of those who wait at least until age 21. The results of this survey are published in Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine.

Federally financed laboratory experiments on the brains of adolescent rats subjected to binge doses of alcohol have shown significant cellular damage to the forebrain and the hippocampus.

And although it is unclear how directly these findings can be applied to humans, there is some evidence to suggest that young alcoholics may suffer analogous deficits.

It was found that alcoholic teenagers performed poorly on tests of attention focusing verbal and nonverbal memory, and exercising spatial skills.

Advertisement

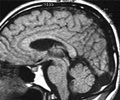

The hippocampus in the brain is a structure crucial for learning and memory. Researchers have found that alcohol drastically suppressed the activity of specific chemical receptors in the region with the suppressive effect being found to be significantly stronger in adolescent rat brain cells than in the brain cells of adult rats.

Advertisement

Other research has also found that while drunken adolescent rats become more sensitive to memory impairment, their hippocampal cells become less responsive than adults' to the neurotransmitter gamma-amino butyric acid, or GABA, which helps induce calmness and sleepiness.

This probably explains why teenagers can drink more than adults before they get sleepy enough to stop. However impairment of their cognitive functions is another side effect of this.

The frontal areas of the adolescent brain are crucial for controlling impulses and thinking through consequences of intended actions — capacities many addicts and alcoholics of all ages lack.

According to Fulton Crews, a neuropharmacologist at the University of North Carolina during human adolescence, the frontal portions of the brain are heavily remolded and rewired, as teenagers learn — often excruciatingly slowly — how to exercise adult decision-making skills, like the ability to focus, to discriminate, to predict and to ponder questions of right and wrong.

"Alcohol creates disruption in parts of the brain essential for self-control, motivation and goal setting," Dr. Crews said, and can compound pre-existing genetic and psychological vulnerabilities. ‘Early drinking is affecting a sensitive brain in a way that promotes the progression to addiction.’

In an experiment, published this year in the journal Neuroscience, Dr. Crews found that even a single high dose of alcohol temporarily prevented the creation of new nerve cells from progenitor stem cells in the forebrain that appear to be involved in brain development.

The damage was found to be far more serious in adolescent rats than in adult rats. It began at a level equivalent to two drinks in humans and increased steadily as the dosage was increased to the equivalent of 10 beers, when it stopped the production of almost all new nerve cells.

Two M.R.I. scan studies, one conducted by Susan Tapert, clinical psychologist at the University of California, San Diego have found that hard-drinking teenagers had significantly smaller hippocampi than their sober counterparts.

In addition Dr Tapert found that teenagers who drink heavily also show a difference in using their brains probably to make up for subtle neurological damage. A study using functional M.R.I. scans, published in 2004, found that alcohol-abusing teenagers who were given a spatial test showed more activation in the parietal regions of the brain, toward the back of the skull, than did non drinking teenagers.

The good news according to Dr Tapert is the fact that the brain is remarkably plastic and future studies may show that the teenage brain, while more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol, is also more resilient.