A method that twins Rwandan physicians with Boston-based pediatric oncologists has shown to improve lymphoma outcomes in young patients.

"We show that we can safely deliver care using this model – an American-trained pediatrician supervising a Rwandan-trained generalist – who are together supervised through phone calls from a U.S-based pediatric oncologist," says Lehmann, who is clinical director of the pediatric stem cell transplant program at Dana-Farber/Children's Hospital Cancer Center.

While nations in the developing world have traditionally devoted their limited public health resources to epidemic infectious diseases such as malaria and diarrhea, life-threatening non-communicable conditions like cancer and heart disease are of growing concern.

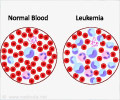

"There are not enough pediatric oncologists in the world" to provide specialized cancer care for children in developing countries, Lehmann says. "And there's not a single trained pediatric oncologist in Rwanda," a country of more than 11 million people.In the Western world, 80 percent of children can be cured of lymphoma, but this success rate requires definitive diagnosis, expert administration of chemotherapy, and experienced follow-up care. The "twinning" team approach leverages in-country medical and nursing resources by adding the long-distance supervision and treatment-planning of Dana-Farber/Children's pediatric specialists in blood cancers.

The children described in Lehmann's report were treated over the past four years at the Rwinkwavu government hospital in rural Rwanda. The hospital is supported by Paul Farmer's Partners In Health, which works with governments in impoverished areas of the world to improve health care.About five years ago, Stulac, a pediatrician then based in Rwanda as the clinical director for Partners In Health's project, set up the care model based at Rwinkwavu, along with Sara Chaffee, MD, of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. Rounding out the group are Alain Uwumugambi, MD, a general physician trained in Rwanda; Merab Nyishime, RN, head pediatric nurse at Rwinkwavu Hospital, and a Rwandan nurse coordinator, Jean Bosco Bigirimana, RN. All are authors on the paper.

Lehmann says that accurate diagnosis of lymphoma is essential and sometimes difficult. "You don't want mistakes," she emphasizes. Children underwent biopsies and staging X-rays in Rwanda, and the results were sent to Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston for all diagnoses.

Advertisement

For radiation therapy, children were taken to facilities in bordering Uganda. Throughout treatment, Lehmann consulted with the team in weekly conference calls – or more often, if needed.

Advertisement

Two patients are currently on chemotherapy and their cancer is in remission. Two children died from treatment-related complications, and a third died when the lymphoma progressed during treatment.

"This is the beginning of a new model," says Lehmann. "In the past, doctors weren't comfortable having complicated oncology care delivered without a local oncology specialist available. Having a specialist on-site would be ideal – but as global health moves into oncology, there are not enough oncologists to provide that kind of care so alternative approaches must be developed and carefully assessed."

Source-Eurekalert