A T-cell receptor that binds to an antigen associated with prostate cancer and breast cancer has been cloned by researchers at Uppsala University.

Genetically modified T cells (white blood corpuscles) have recently been shown to be extremely effective in treating certain forms of advanced cancer. T cells from the patient's own blood cells are isolated and equipped by genetic means with a new receptor that recognizes an antigen that is expressed in the tumour cells. These T cells are cultivated in a special clean room and then administered to the patient. Once inside the body, they seek out sub tumours and individual tumour cells and eliminate them.

This form of treatment attracted major attention in the world media last autumn when researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, managed to cure two of three patients with an otherwise incurable form of leukaemia (Kalos et al., Sci Transl Med 3:95ra73, 2011; Porter et al., N Engl J Med 365:725-33, 2011). Trials with genetically modified T-cells have also met with some success in treating malignant melanoma at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda (Morgan et al., Science 314:126-9, 2006).

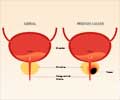

Magnus Essand's research team at Uppsala University has now taken the first steps towards making this highly promising form of therapy feasible also for the major public health diseases prostate cancer and breast cancer.

"This is definitely a step along the way to a form of therapy also for our two largest cancer types (prostate cancer and breast cancer)."

Genetically modified T cells are one of two promising avenues the research team is pursuing in order to develop new treatments for cancer. It has taken nearly three years for the scientists to clone the T-cell receptor and then demonstrate its therapeutic capacity.

Advertisement

Every T cell has a unique T-cell receptor, which entails great potential to recognize alien antigens and, for example, kill virus-infected cells. T-cells can also recognize and kill tumour cells, but there aren't enough of them normally to carry out the task. However, if it is known which unique antigen is expressed by a tumour cell type, it should be possible to clone a T-cell receptor that has the capacity to bind to that antigen. This receptor can then be conveyed to the cancer patient's own T cells and used as treatment.

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert