Neuroscientists develop potential tool for the study of brain function. This new thermogenetic tool is made from the Drosophila gustatory receptor family could aid research in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease.

‘This study reports the development a new thermogenetic tool based on the Drosophila gustatory receptor family. Thermogenetic tools enable temporally precise control of electrical activity of specific neurons.’

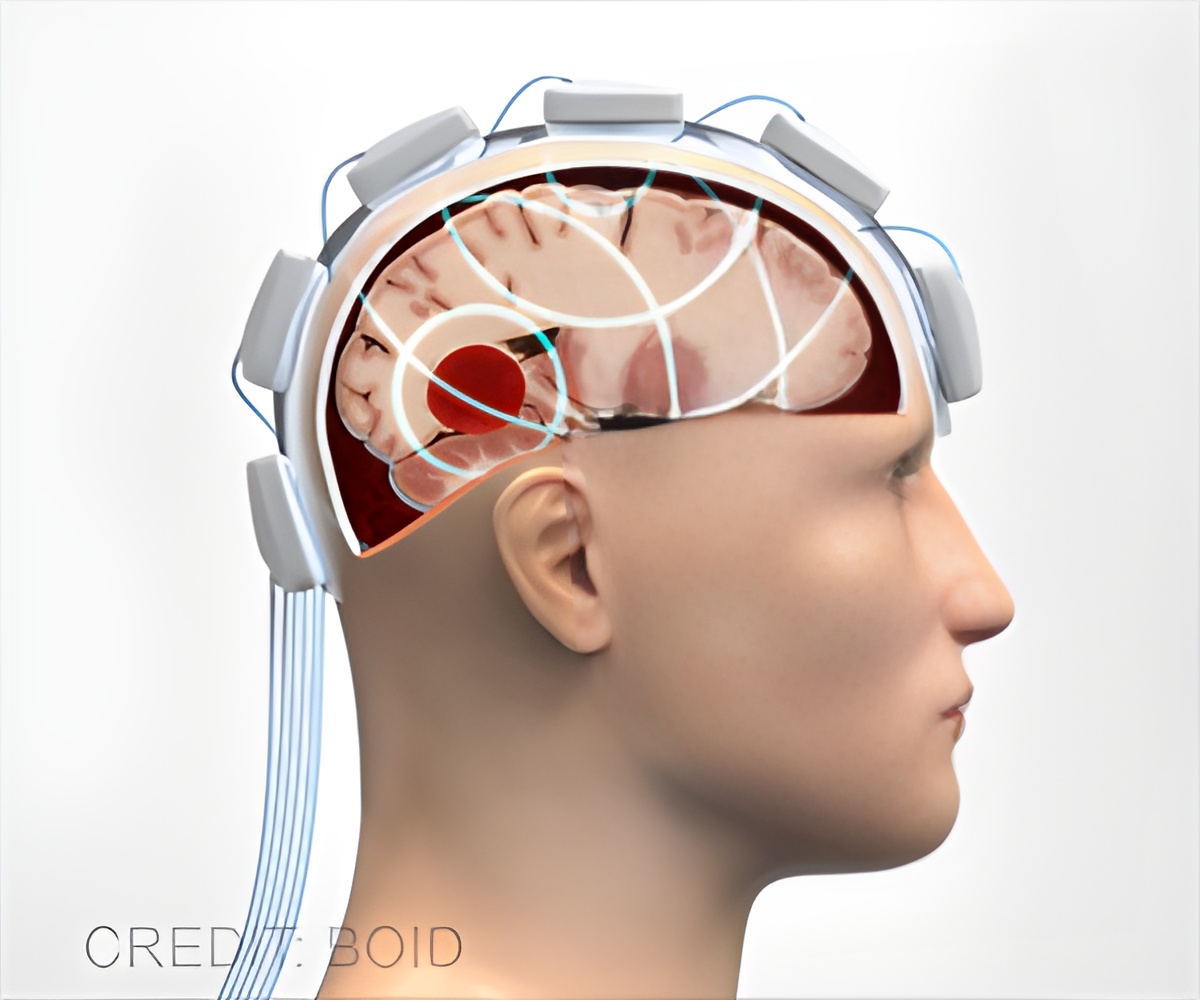

"Thermogenetic tools, which utilize heat to act as a 'switch' to turn neuron functions on, are expanding the horizons of brain research by allowing us to control specific neurons in the brain and measure behavioral changes," said Troy Zars, professor of biological sciences in the MU College of Arts and Science. "The goal of this fundamental research was to identify more of these special proteins, laying the foundation so that, in the future, scientists have a better understanding of how neuronal circuits function." The research team was led by Zars, as well as Mirela Milescu and Lorin Milescu, who both are assistant professors of biological sciences at MU. The team included four undergraduate and four graduate students. Together, the researchers focused on a family of genes that encode taste receptors found in fruit flies. Surprisingly, some of these taste receptors also are activated by heat and thus play a role in detecting environmental temperature.

First, the students in Mirela Milescu's lab investigated the thermosensitivity of these proteins and identified one member of the family, called Gr28bD, as a prime candidate for thermogenetics. Then, Lorin Milescu's students used live-imaging techniques and software developed in their lab to demonstrate that the Gr28bD protein can, through temperature differences, modulate the brain activity of fruit flies.

Finally, the flies were tested in Dr. Troy Zars' lab for temperature-dependent behavior. Using a specially designed heat chamber that allows precise control of the environmental temperature, the Zars' students were able to show that the Gr28bD protein can control behavior in these flies, using temperature as a "brain switch."

"Gr28bD could become a powerful tool in controlling neuronal activity and studying how neuronal circuits function," said Benton Berigan, a graduate student in Lorin Milescu's lab. "Since this protein is not found in any mammal, it emerges as a good candidate for the development of novel thermogenetic tools to be used for basic research and potentially one day in humans."

Advertisement

This research highlights the power of translational precision medicine and the promise of the proposed Translational Precision Medicine Complex (TPMC) at the University of Missouri. The TPMC will bring together industry partners, multiple schools and colleges on campus, and the federal and state government to enable precision and personalized medicine. Scientific advancements made at MU will be effectively translated into new drugs, devices and treatments that deliver customized patient care based on an individual's genes, environment and lifestyle, ultimately improving health and well-being of people.

Advertisement