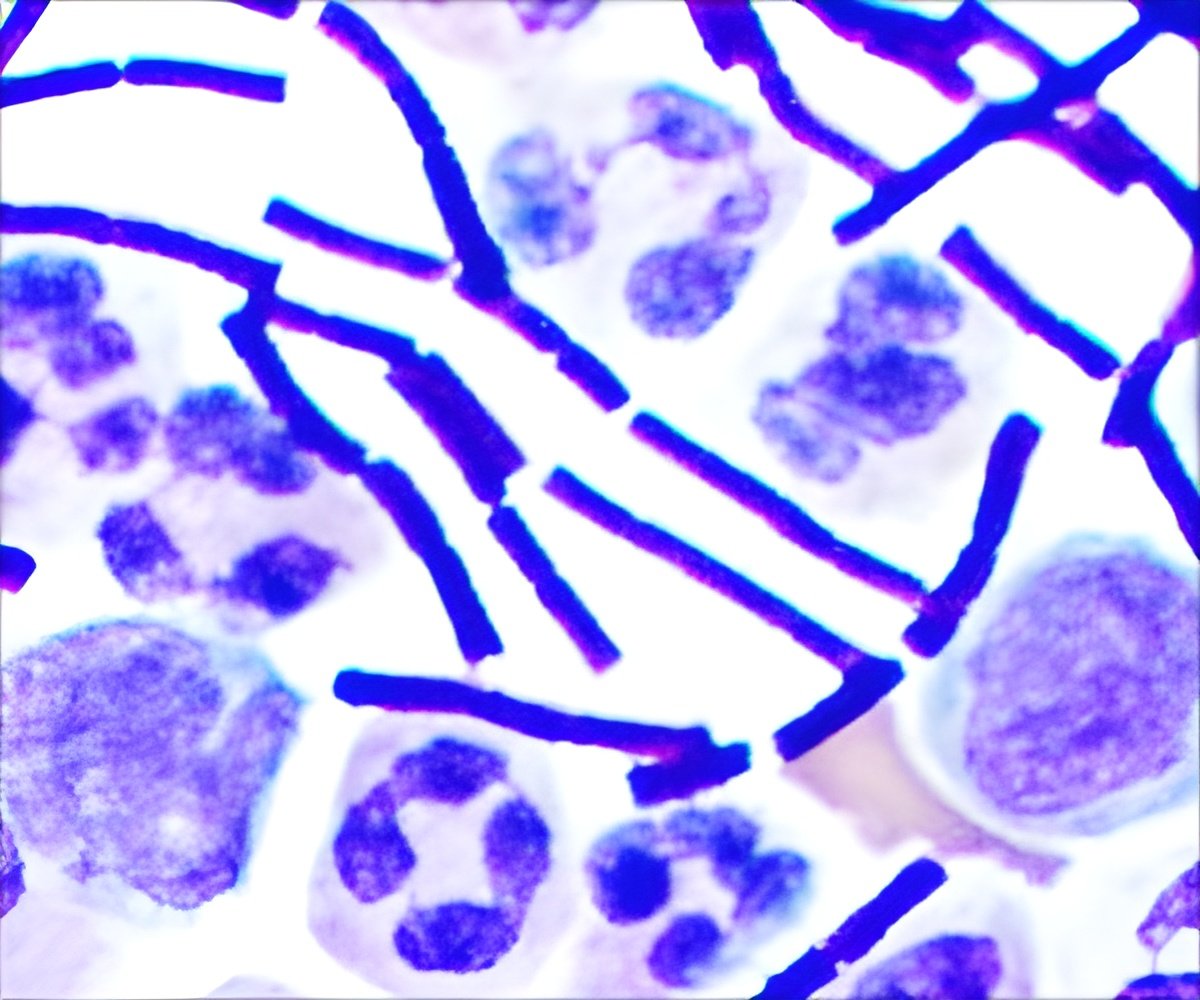

Patterns in the outer protein coat of group A Streptococcus bacteria have been uncovered by University of California San Diego researchers.

‘Sequence patterns in the major surface protein and virulence factor of group A Strep bacteria have been discovered.’

"At present, there is no vaccine against group A Strep, and our discovery of hidden sequence patterns has offered up a novel way to devise such a vaccine," said Partho Ghosh, chair of UC San Diego's Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, who headed the team of researchers.

Ghosh said that one of the biggest obstacles to the development of a vaccine against these bacteria is the "hyper-variability" of the M protein. Group A Streptococcus bacteria have a multitude of different strains, each of which displays a different protein on its surface. Because our immune systems must recognize these different proteins before launching an immune response with antibodies specific to the outer protein coat, the hyper-variability of the M proteins make it difficult for our immune systems to attach antibodies specific to each these proteins from different strains.

"When we become infected with a particular strain of group A Strep, we generally mount an immune response against the particular M protein displayed by that strain," explains Ghosh. "But this immunity works only against the infecting strain. We remain vulnerable to infection by other group A Strep strains that display other types of M proteins on their surfaces. This is because the antibody response against the M protein is almost always specific to the sequence of that M protein, and M proteins of different types appear to be unrelated in sequence to one another."

The key to resolving the problem was the recognition that a human protein called C4BP had been discovered by another group of researchers to be recruited to the surface of Group A Strep by many different protein types.

Advertisement

To determine if this was possible, a graduate student in Ghosh's lab, Cosmo Buffalo, collaborated with another graduate student, Sophia Hirakis, in the laboratory of Rommie Amaro, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry who uses computers to study protein structures, to first study the complex interactions between M protein and C4BP.

Advertisement

In their experimental and computational study, the biochemists painstakingly detailed four crystal structures of four different M protein types, each bound to human C4BP.

"These structures revealed that even though the different M protein types appeared to be unrelated in sequence, there were common sequence patterns hidden within the differences that linked all these M proteins together," said Ghosh. "These common patterns are what is used to recruit C4BP to the surface of group A Strep by the different M protein types."

"The idea now is to have antibodies do the same thing as C4BP -- that is, recognize many different M protein types," he added. "That way, the antibody response will not be limited to one M protein type and one strain of group A Strep, but will extend to most, if not all, M protein types and most, if not all strains, of group A Strep."

The UC San Diego chemists, in collaboration with Nizet, are now working on developing a vaccine that, they hope, will be protective against most, if not all, strains of group A Strep

Source-Eurekalert