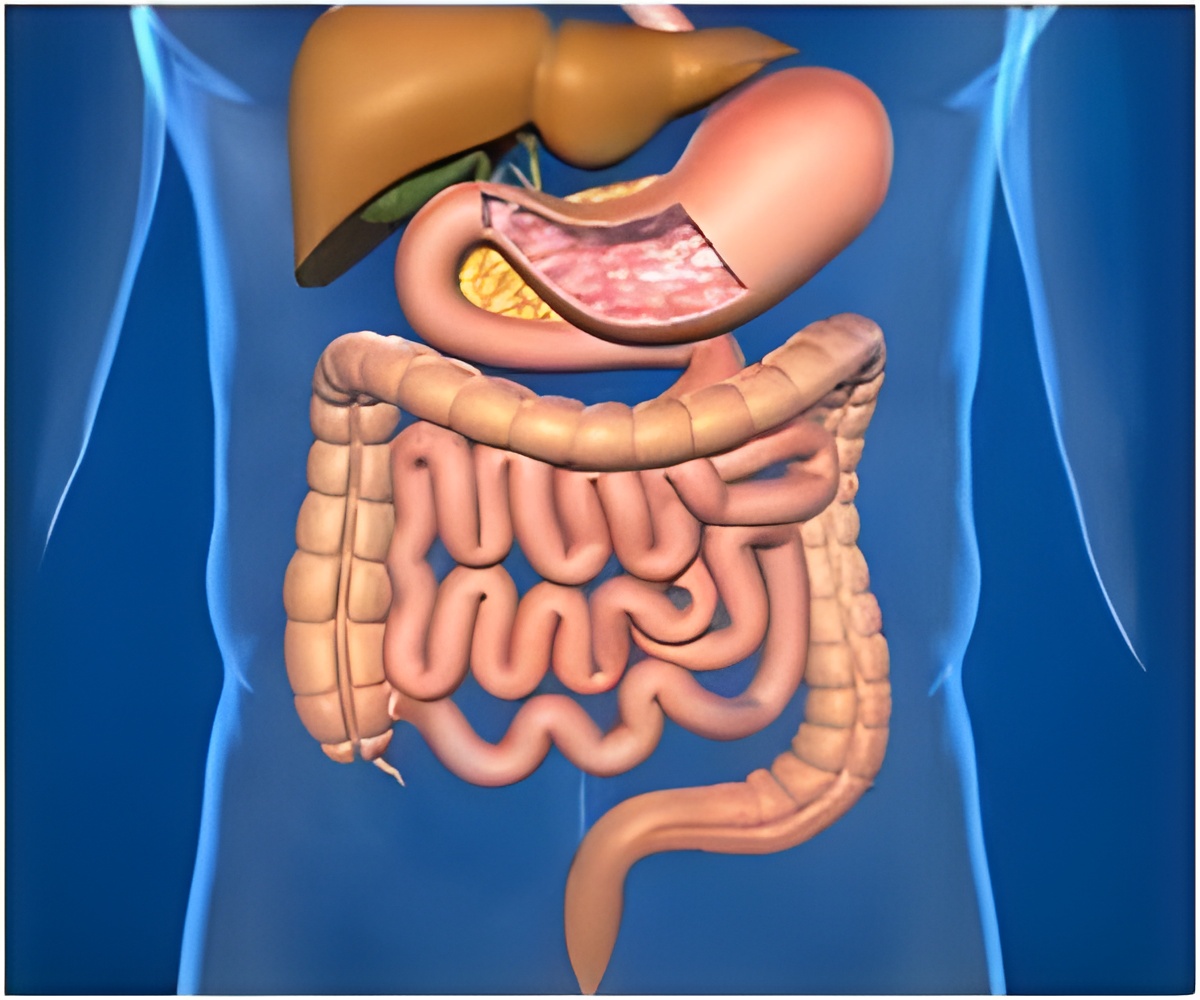

Certain genetic variations are associated with susceptibility to Helicobacter pylori, a bacteria that is a major cause of gastritis, stomach ulcers and is linked to stomach cancer.

Julia Mayerle, M.D., of University Medicine Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany, and colleagues conducted a study to identify genetic loci associated with H pylori seroprevalence. Two independent genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and a subsequent meta-analysis were conducted for anti-H pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) serology in the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) (recruitment, 1997-2001 [n =3,830]) as well as the Rotterdam Study (RS-I) (recruitment, 1990-1993) and RS-II (recruitment, 2000-2001 [n=7,108]) populations. Whole-blood RNA gene expression profiles were analyzed in RS-III (recruitment, 2006-2008 [n = 762]) and SHIP-TREND (recruitment, 2008-2012 [n=991]), and fecal H pylori antigen in SHIP-TREND (n=961).

Of 10,938 participants, 6,160 (56.3 percent) were seropositive for H pylori. GWAS meta-analysis identified an association between the gene TLR1 and H pylori seroprevalence, "a finding that requires replication in non-white populations," the authors write.

"At this time, the clinical implications of the current findings are unknown. Based on these data, genetic testing to evaluate H pylori susceptibility outside of research projects would be premature."

"If confirmed, genetic variations in TLR1 may help explain some of the observed variation in individual risk for H pylori infection," the researchers conclude.

Editorial: Helicobacter pylori Susceptibility in the GWAS Era

Advertisement

"This would be superfluous, because nongenetic testing for the infection can be accomplished at a fraction of the cost. There is a bigger picture: understanding genetic susceptibility to H pylori is essential for understanding how to overcome this infection. The current approach to eradication of the infection is limited and based entirely on prescribing a cocktail of antibiotics with an acid inhibitor to symptomatic individuals. However, H pylori antibiotic resistance is increasing steadily, and eventually curing even benign conditions such as peptic ulcer disease arising from H pylori will be difficult. When considering gastric cancer, another H pylori-induced global killer, the necessity for understanding the pathogenesis of the infection and the role of host genetics in susceptibility is even greater. The corollary is that better understanding of infections, including genetic epidemiology, is crucial to design measures to eradicate the downstream consequences of H pylori in large populations."

Advertisement