Experiments on mice suggest that cancer patients in the future may benefit from a new type of cancer immunotherapy; behind the study is a number of international researchers with Anders Etzerodt from Aarhus University, Denmark, as the lead author

‘Removing specific macrophages which express CD163 can make T cells and various other macrophages attack the tumour and shrink it.’

Read More..

"We've studied what happens to the tumour when it is exposed to targeted treatment that removes precisely ten per cent of the macrophages that are supporting the cancer tumour instead of fighting it," says Anders Etzerodt, PhD and assistant professor in cancer immunology at the Department of Biomedicine at Aarhus University.Read More..

He is the lead author of the study which is currently being shared diligently on Twitter by researchers in the field.

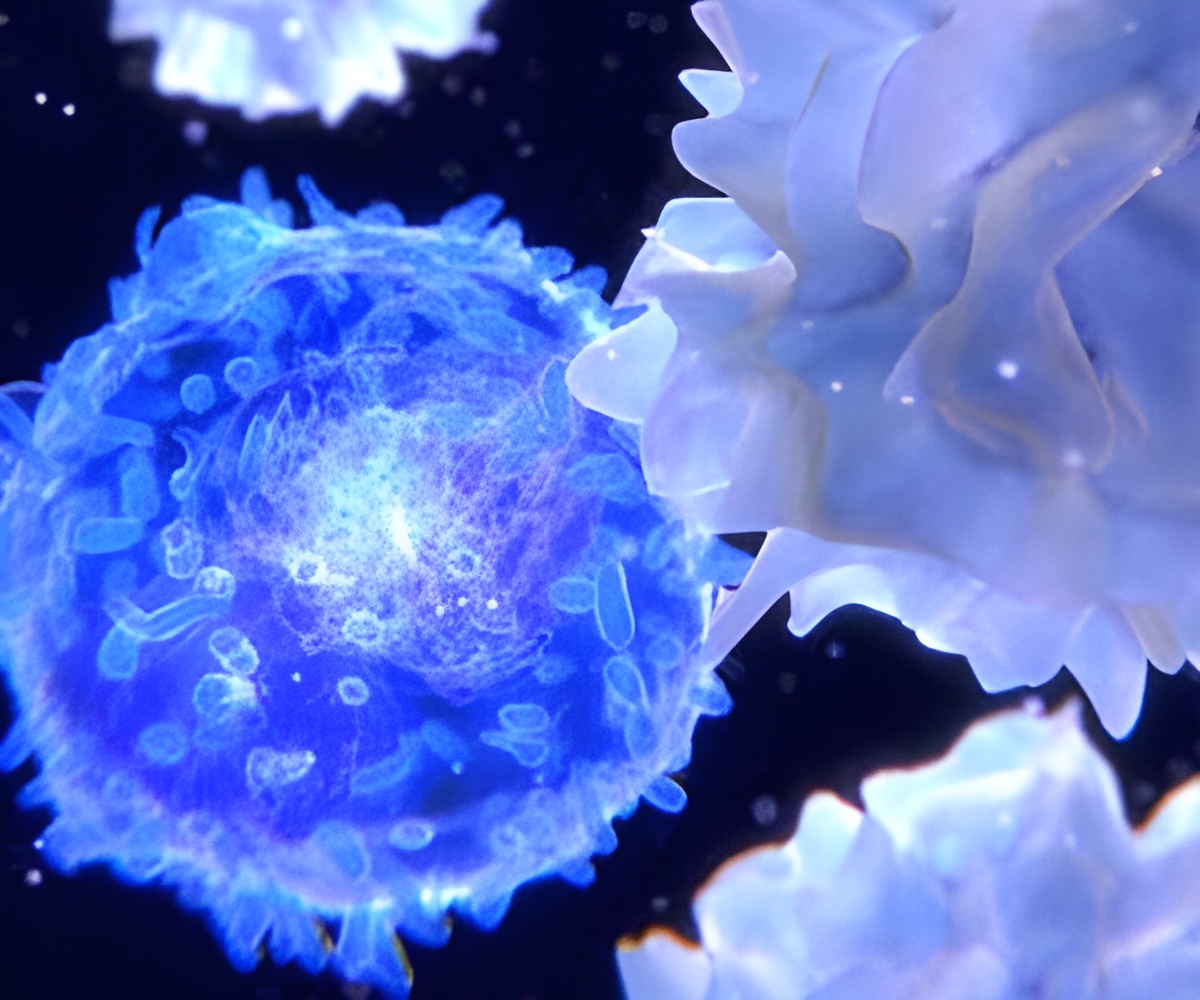

"The most important result is that the depletion of this specific type of macrophage causes the tumour to shrink, which is triggered by a subsequent mobilisation of new macrophages and, ultimately, also an activation of the so-called T cells which attack the tumour," says Anders Etzerodt.

The type of macrophages which the researchers have removed express a specific receptor, CD163, on the cell surface. Unlike other macrophages, these are known to have an undesirable effect in connection with cancer. Instead of recognising cancer cells as unwanted tissue, the macrophage sees the tumours as normal tissue that needs help with regeneration. It is also widely recognised that survival rates are worse if there are many macrophages, which express the CD163 receptor in the tumour.

"Our study suggests that the macrophages we're hitting function as a kind of 'peacekeeping' force that keeps the 'attackers' away," says Anders Etzerodt.

Advertisement

Anders Etzerodt adds that discovering that it is actually possible to target medical chemotherapy treatment so that it precisely hits the macrophages that are negative markers for survival is in itself an important finding.

Advertisement

The research group with Anders Etzerodt and research partners are currently testing whether the technique works just as well on mice with other kinds of cancer in which CD163 is a sign of low survival rates. These ongoing research projects focus on both cancer of the ovaries and cancer of the pancreas, and Anders Etzerodt does not hide the fact that there are still unanswered questions and issues that need to be dealt with:

"We don't know the long-term effects of removing macrophages, and we must also find partners to collaborate with and funding from foundations so we can conduct clinical trials on humans. But I believe we are well-prepared with strong proof-of-concept data and patent applications," says Anders Etzerodt, who has also worked on the idea in a leading French macrophage laboratory at the Centre d'Immunologie Marseille-Luminy. His stay here was made possible by a four-year postdoc fellowship from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Source-Eurekalert