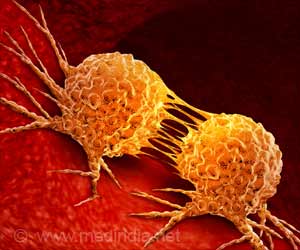

Many people with cancer have radiotherapy. Research shows that at least one in two people with cancer would benefit from radiotherapy treatment.

‘Radiotherapy kills or damages cancer cells in the area being treated. Cancer cells begin to die within days or weeks of treatment starting and continue to die for weeks or months after it finishes.’

A new CU Boulder study sheds new light on the precise mechanism behind RIBE, identifying both a protein released by irradiated cells and the pathway it takes to influence healthy ones. Ultimately, researchers hope it could lead to a medication patients could take before radiation treatment. Lead author Ding Xue noted that inhibiting RIBE would allow doctors to kill two birds with one stone. "We could minimize the bad effects of radiotherapy on healthy bystander cells, and at the same time, enhance cancer cell killing by radiotherapy." Nine years in the making, the study used a translucent, 1,000-cell worm called C. elegans, as a model to study the bystander effect in action. First, to be sure RIBE occurred in C. elegans, researchers exposed a population of the worms to radiation, then took a medium secreted by the C. elegans cells and bathed healthy C. elegans in it. The once-healthy animals began to show increased embryo deaths and other signs of RIBE. The researchers then systematically treated the medium with agents designed to destroy proteins, DNA, and RNA, in order to determine which may be a key compound at play in RIBE. When the medium was treated with a protease, which breaks down proteins, C. elegans exposed to it did not show signs of RIBE.

Once researchers discovered that the agent causing RIBE was a protein, they used a technique called mass spectrometry to establish which proteins present in the medium were at play. A protein called CPR-4, the C. elegans version of a human protease called cathepsin B, emerged as the prime candidate. Cathepsin B is known to be a biomarker in several types of cancer. Then researchers studied which biological pathway enabled CPR-4 to signal changes in healthy cells that were never exposed to radiation.

They identified a pathway mediated by the insulin-like growth factor receptor DAF-2. To confirm these findings, they irradiated the heads of C. elegans who either lacked the gene that codes for CPR-4 or lacked the gene that codes for insulin-like growth factor receptor DAF-2. The bystander effect was blunted, with cells elsewhere in the body remaining healthy. The study also found that a tumour suppressor gene called P53 may be at play in RIBE, prompting cells to produce more of the damaging CPR-4 protein when a cell is exposed to radiation.

Xue, who hopes to work with other researchers in the future to identify other RIBE factors and mechanisms and help develop drugs that inhibit them, said "We are excited about these findings and believe they could have broad implications for patients as well as other important areas such as radiation protection and radiation safety." The study is published in the journal Nature.

Advertisement