A new method to treat acute myeloid leukemia uses the gene editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 to remove CD33 from healthy blood-forming stem cells, leaving the cancerous cells as the only targets left for the CD33 hunter cells to attack.

‘In the treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia, researchers have identified a new method to target and remove a specific protein - CD33 from healthy blood-forming stem cells. This will leave cancerous cells as the only targets for the CD33 hunter cells to attack.’

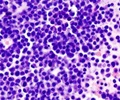

The new method uses the gene editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 to remove CD33 from healthy blood-forming stem cells, leaving the cancerous cells as the only targets left for the CD33 hunter cells to attack. Penn researchers and their collaborators at the National Institutes of Health published their proof-of-concept findings in Cell. AML is the second most common type of leukemia, and the American Cancer Society estimates there will be almost 20,000 new cases in the United States this year. Many of these patients will undergo a bone marrow transplant. To treat a related leukemia called acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL), investigators at Penn previously developed CAR T cell therapy, which involves collecting patients' own immune T cells, reprogramming them to kill cancer, and then infusing them back into patients' bodies.

Currently, both CAR T cell therapies approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration target cells that express a protein called CD19, for ALL and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. However, this is not an effective target for AML, since AML does not express CD19. Researchers have therefore been looking for other potential cellular targets.

One promising example is a protein known as CD33, but previous attempts to target CD33 have proven damaging to healthy cells. While damage to healthy cells could be prevented by making the CART cells short-lasting, this would defeat the purpose of one of CAR T's greatest strengths - their ability to last for years, circulate in the body, and protect the patient from relapse.

"This therapy is meant to be a true living drug, and we know that CAR T cells can live on in patients' bodies for years after infusion, so turning them off would be self-defeating," said the study's co-senior author Saar I. Gill, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of Hematology-Oncology at Penn. Cynthia E. Dunbar, MD, a senior investigator at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, is a co-senior author. The co-first authors are Miriam Yunhee Kim, MD, then a post-doctoral researcher in Gill's lab, and Kyung-Rok Yu PhD, a post-doctoral fellow under Dunbar.

Advertisement

Since the hunter cells are unable to distinguish between normal and malignant cells, the researchers developed an innovative approach to genetically engineer the normal stem cells so they no longer resemble the leukemia. They used the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing tool to remove CD33 from healthy cells. To their surprise, healthy stem cells lacking CD33 functioned normally. This resulted in the CD33 protein now being unique to the leukemia cells, leaving the CAR T cells free to attack.

Advertisement

Gill and his team have already put this concept into practice and have shown it to be effective in mouse and monkey models. They've also demonstrated its effect on human cells in a laboratory setting.

"Think of this as bone marrow transplant 2.0; the next generation of transplants," Gill said. "It gives you a super powerful anti-leukemia effect thanks to the CAR T cells, but at the same time it has the potential to get rid of the main toxicity."

Their next step is to move this approach into human trials at Penn.

Source-Eurekalert