Researchers have developed a new molecular sensor that can perform real time detection of high levels of metabolic acid lactate in individual cells.

"Over the last decade, the Frommer lab at Carnegie has pioneered the use of Förster Resonance Energy Transfer, or FRET, sensors to measure the concentration and flow of sugars in individual cells with a simple fluorescent color change. This has started to revolutionize the field of cell metabolism," explained CECs researcher Alejandro San Martín, lead author of the article. "Using the same underlying physical principle and inspired by the sugar sensors, we have now invented a new type of sensor based on a transcriptional factor. A molecule that normally helps bacteria to adapt to its environment has now been tricked into measuring lactate for us."

Lactate shuttles between cells and inside cells as part of the normal metabolic process. But it is also involved in diseases that include inflammation, inadequate oxygen supply to cells, restricted blood supply to tissues, and neurological degradation, in addition to cancer.

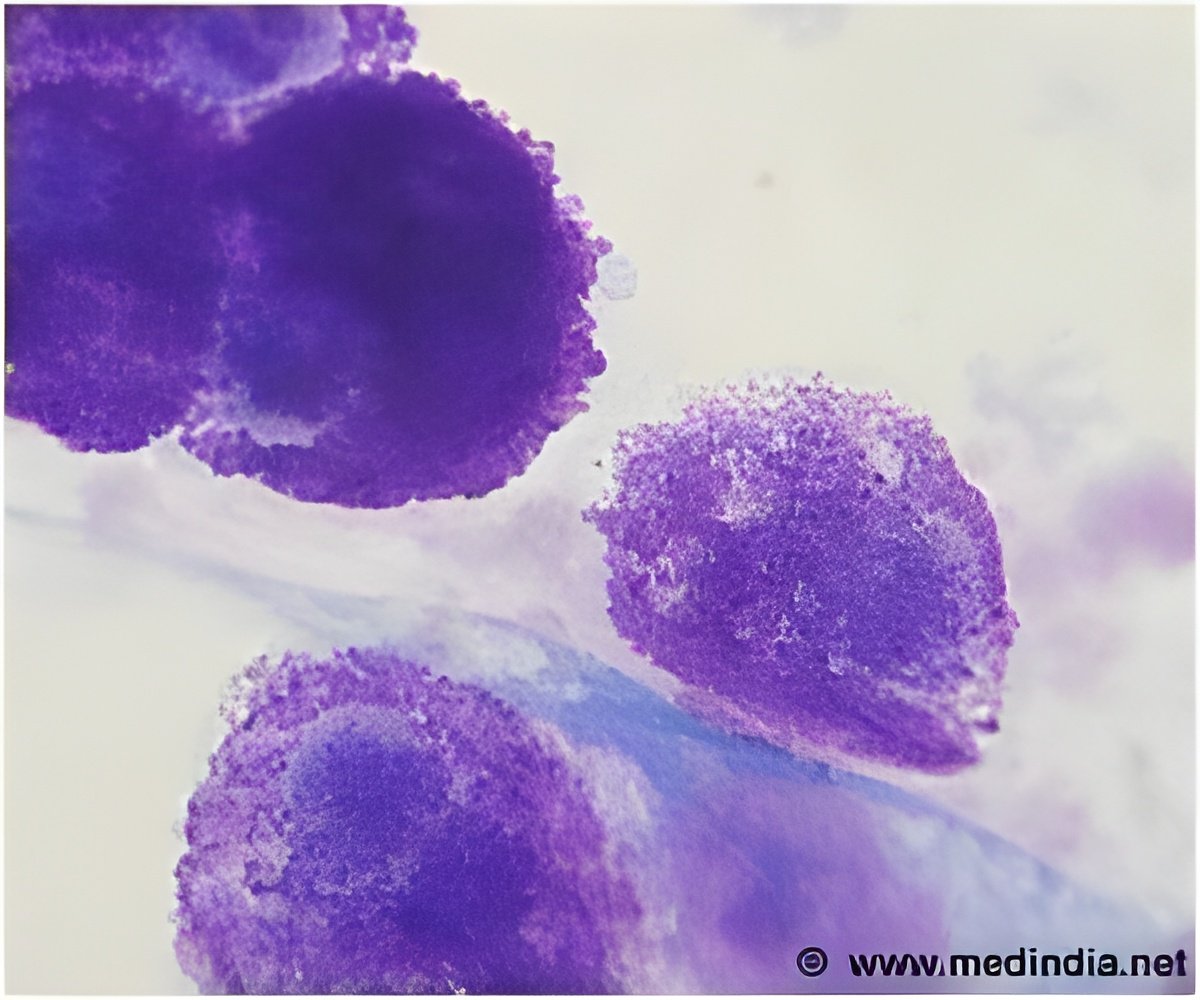

"Standard methods to measure lactate are based on reactions among enzymes, which require a large number of cells in complex cell mixtures," explained Felipe Barros, leader of the project. "This makes it difficult or even impossible to see how different types of cells are acting when cancerous. Our new technique lets us measure the metabolism of individual cells, giving us a new window for understanding how different cancers operate. An important advantage of this technique is that it may be used in high-throughput format, as required for drug development."

This work used a bacterial transcription factor—a protein that binds to specific DNA sequences to control the flow of genetic information from DNA to mRNA—as a means to produce and insert the lactate sensor. They turned the sensor on in three cell types: normal brain cells, tumor brain cells, and human embryonic cells. The sensor was able to quantify very low concentrations of lactate, providing an unprecedented sensitivity and range of detection.

The researchers found that the tumor cells produced lactate 3-5 times faster than the non-tumor cells. "The high rate of lactate production in the cancer cell is the hallmark of cancer metabolism," remarked Frommer. "This result paves the way for understanding the nuances of cancer metabolism in different types of cancer and for developing new techniques for combatting this scourge."

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert