Only one class of chemotherapy, namely taxanes, is effective against prostate cancer, the second leading cause of cancer for men in the United States.

"It was surprising to find that cabazitaxel functions differently than docetaxel in killing cancer cells, even though they're both taxanes," says senior author Karen Knudsen, Ph.D., Interim Director of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center and a professor of cancer biology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. "It shows that we may not be taking full advantage of this next generation taxane in the clinic."

For years, docetaxel has been the only effective chemotherapy for men whose cancer was no longer responding to hormone treatments. The next generation drug in the taxane family, cabazitaxel, was approved in 2010, but only for patients whose cancer no longer responded to hormone therapy or docetaxel treatment.

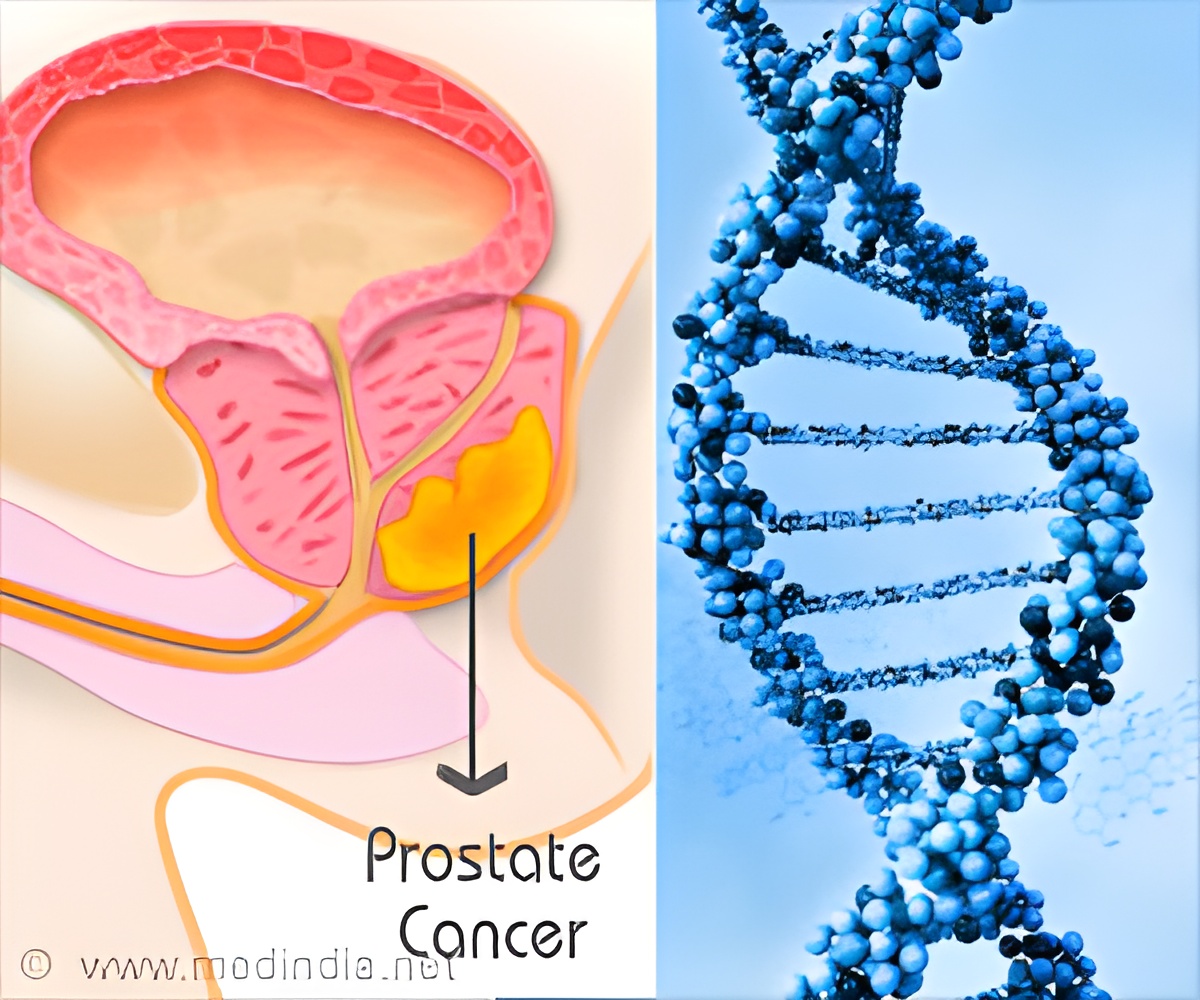

Knudsen and colleagues explored how cabazitaxel worked and demonstrated that it might be more effective sooner in treatment. The researchers showed that cabazitaxel worked better than docetaxel in human prostate cancer cells lines that were resistant hormone treatment, both in terms of slowing cancer-cell growth and in its ability to kill cancer cells. Analysis of the tumor genes affected by the two drugs revealed that cabazitaxel had a greater effect on cellular division and regulation of chromatin - a spool for DNA that helps control which genes are in use and when - whereas docetaxel has a greater impact on DNA transcription and repair. "This difference in mechanism suggests that we should treat these two drugs less like members of the same family, and more like two distinct therapies that may each have distinct benefits for certain patients," says first author Renée de Leeuw, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of cancer biology at Thomas Jefferson University.

In order to test their hypothesis in a model that more closely mimicked human disease, the researchers also tested the two drugs side-by-side on slices of tumors removed from patients during radical prostatectomy. The tissues were grown on a 3D gelatin sponge, and two portions of the same tumor were treated with either cabazitaxel or docetaxel. The results confirmed that cabazitaxel was more effective at killing tumor cells than docetaxel. "The ability to test our ideas in tumor tissues removed from patients underscores the unique and multi-disciplinary nature of our Prostate Cancer Program, one of only eight Prostate Cancer Programs of Excellence in National Cancer Institute Designated Centers," said Dr. Knudsen. "Notably, key contributors to the study included leaders in Urology, Medical Oncology and Radiation Oncology, Drs. Leonard Gomella, W. Kevin Kelly, and Adam Dicker."

The collaborative research team also found a molecular marker that would help identify patients most likely to benefit from cabazitaxel treatment. Knudsen and colleagues showed that tumors whose retinoblastoma (RB) gene no longer worked were likely to become hormone resistant, but remarkably were more likely to respond to cabazitaxel. "This gene could give us a way to identify patients who would benefit from cabazitaxel earlier and reduce the trial and error of treating a cancer patient," says Dr. Knudsen.

Advertisement

"These results from our laboratory research give us a strong reason to believe that this drug could be more useful to some men earlier in their course of treatment," says Dr. Knudsen. "The ABICABAZI trial puts these ideas to the test in humans, and if we are correct, has the capacity for the first time to tell us what patients might most benefit from chemotherapy."

Advertisement