miR-132 was found to protect against toxic amyloid-beta and tau in both rodent models and human neurons.

‘miRNAs that showed neuroprotective effects have been discovered by scientists. miRNAs hold potential as a treatment for tauopathies.’

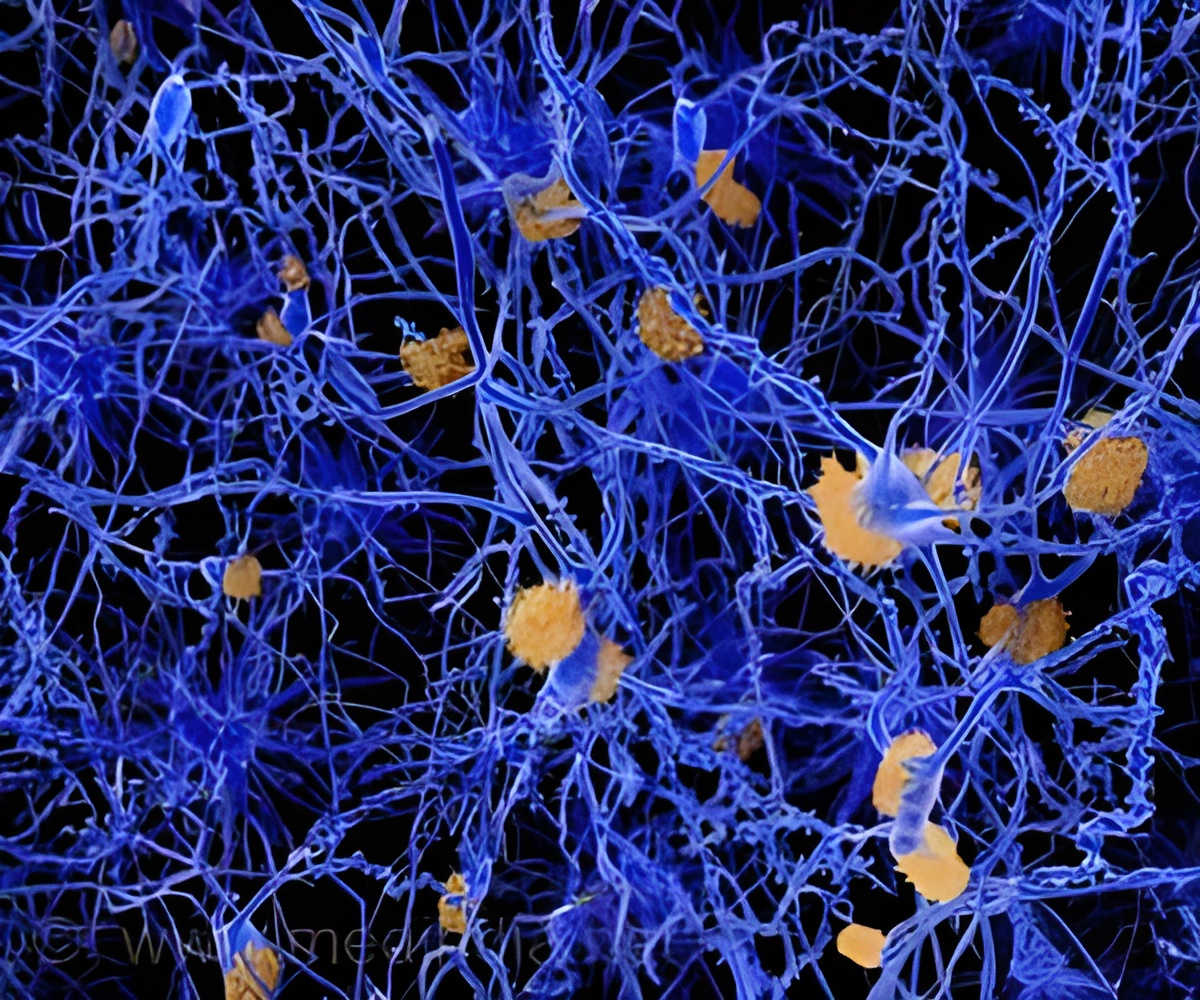

A study by researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH), recently published in Acta Neuropathologica, investigated lesser-known molecules involved in tauopathies like Alzheimer's. They focused on microRNAs (miRNAs), gene expression regulators that bind to and destroy protein-encoding messenger RNAs. "Our results support the idea that miR-132 is a master regulator of neuronal health with potential as a treatment target," said lead investigator and BWH scientist, Anna Krichevsky, PhD.

The team first looked at primary cortical and hippocampal neurons taken from both normal and tauopathic mice. To examine the neuroprotective properties of naturally occurring miRNAs, they tested 63 neuronal miRNAs, then inhibited them with miRNA-binding molecules called anti-miRNAs. They found that inhibition of some miRNAs seemed to protect against, and others to exacerbate, amyloid-beta pathology and associated glutamate excitotoxicity. Of these, miR-132 was the most neuroprotective miRNA.

They confirmed the neuroprotective properties of miR-132 by designing miR-132 mimics and introducing them to the mouse cells. They observed reduced levels of toxic forms of tau, glutamate excitotoxicity and cell death. They also examined miR-132 supplementation in live mice models of human neurodegenerative disease by injecting miR-132 by way of a viral vector. Compared to controls, miR-132-injected mice showed reduced tau pathology and enhanced hippocampal long-term potentiation, a process involved in memory formation.

When the researchers next introduced miR-132 mimics to human cells, they saw similar results: reduced toxic forms of tau and less cell death.

Advertisement

"Now that we have the knowledge and technologies that enable manipulation of miRNA, we can explore new possibilities," said Krichevsky. "In the last 30 years, research has focused mostly on amyloid. We're still hopeful about that approach, but we must invest in new strategies as well."

Advertisement