New strain of the novel coronavirus called G614 that is spreading around the globe is more infectious than its predecessor D614 strain. A small variation has made the coronavirus fitter but not more deadly, reveals a new study.

‘The new strain of novel coronavirus is called G614, and the previous strain is D614. The new mutation is now the dominant form of infecting people.

’

Read More..

Scientists now know that two variants of the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) were circulating at that time. The variants, called G614 and D614, had just a small difference in their "spike" protein—the viral machinery that coronaviruses use to enter host cells.Read More..

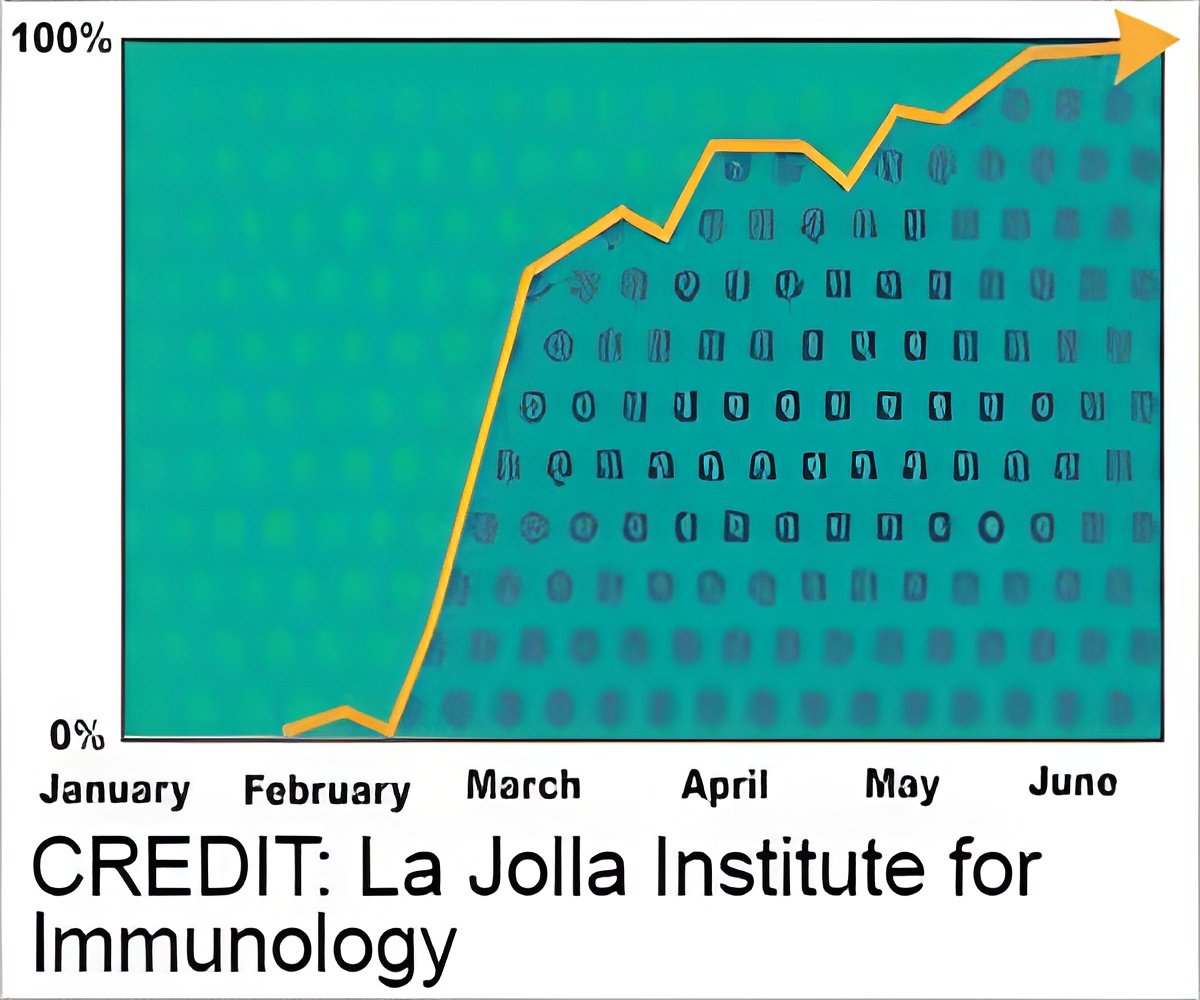

In a new study, an international team of scientists shows that the G version of the virus has come to dominate cases around the world. They report that this mutation does not make the virus more deadly, but it does help the virus copy itself, resulting in a higher viral load, or "titer," in patients.

"We are focused on the human immune response because LJI is the headquarters for the Coronavirus Immunotherapy Consortium (CoVIC), a global collaboration to understand and advance antibody treatments against the virus," says LJI Professor Erica Ollmann Saphire, Ph.D., who leads the Gates Foundation-supported CoVIC.

Saphire explains that viruses regularly acquire mutations to help them "escape" antibodies made by the human immune system. When a virus acquires many of these individual changes, it "drifts" away from the original virus. Researchers call this phenomenon "antigenic drift." Antigenic drift is part of the reason you need a new flu shot each year.

It is extremely important for researchers to track antigenic drift as they design vaccines and therapeutics for COVID-19.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Saphire and co-author David Montefiore, Ph.D., of Duke University Medical Center, led research into the immune response to these variants. They determined that viruses carrying spike with the G mutation grew two to three times more efficiently, leading to a higher titer. Saphire and her colleagues then used samples from six San Diego residents to test how human antibodies neutralized the D and G viruses. Would the fast-growing G virus be harder to fight?

Advertisement

"The clinical data in this paper from the University of Sheffield showed that even though patients with the new G virus carried more copies of the virus than patients infected with D, there wasn't a corresponding increase in the severity of illness," says Saphire.

Korber adds, "These findings suggest that the newer form of the virus may be even more readily transmitted than the original form—whether or not that conclusion is ultimately confirmed, it highlights the value of what were already good ideas: to wear masks and to maintain social distancing."

Saphire says the novel coronavirus could be successful precisely because many patients only get a mild version or no symptoms.

"The virus doesn't 'want' to be more lethal. It 'wants' to be more transmissible," Saphire explains. "A virus 'wants' you to help it spread copies of itself. It 'wants' you to go to work and school and social gatherings and transmit it to new hosts. Of course, a virus is inanimate—it doesn't 'want' anything. But a surviving virus is one that disseminates further and more efficiently. A virus that kills its host rapidly doesn't go as far—think of cases of Ebola. A virus that lets its host go about their business will disseminate better—like with the common cold."

So while the G mutation doesn't make cases more severe, a different mutation might. "We'll be keeping an eye on it," says Saphire.

The study, titled, "Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus" was supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC) part of UK Research & Innovation (UKRI); the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR); Genome Research Limited, operating as the Wellcome Sanger Institute; a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellowship (110058/Z/15/Z); CoVIC, INV-006133 of the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator, supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Mastercard, Wellcome; private philanthropic support, as well as the Overton family; a FastGrant, from Emergent Ventures, in aid of COVID-19 research; and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Interagency Agreement No. AAI12007-001-00000.

Additional study authors included W.M. Fischer, S. Gnanakaran, H. Yoon, J. Theiler, W. Abfalterer, N. Hengartner, E.E. Giorgi, T. Bhattacharya, B. Foley, K.M. Hastie, M.D. Parker, D.G. Partridge, C.M. Evans, T.M. Freeman, T.I. De Silva, C. McDanal, L.G. Perez, H. Tang, A. Moon-Walker, S.P. Whelan, and C.C. LaBranche.

Source-Newswise