Bacterial strains interact differently by making themselves more or less resistant to antibiotics. New antibiotics can be developed to enhance antibiotic susceptibility.

‘New antibiotics can be created by including susceptibility-enhancing factors and blocking susceptibility-reducing factors to fight against bacterial infections.’

The findings, published in PLoS Biology, point to the possibility of new antibiotics employing these factors to enhance antibiotic susceptibility.The research also shows how understanding the precise mix of bacteria and their interactions could become a standard part of clinical practice in treating bacterial infections, especially the more dangerous infections involving antibiotic resistance. Doctors currently gauge the antibiotic susceptibility of an infecting bacterial species by examining it in isolation from other species.

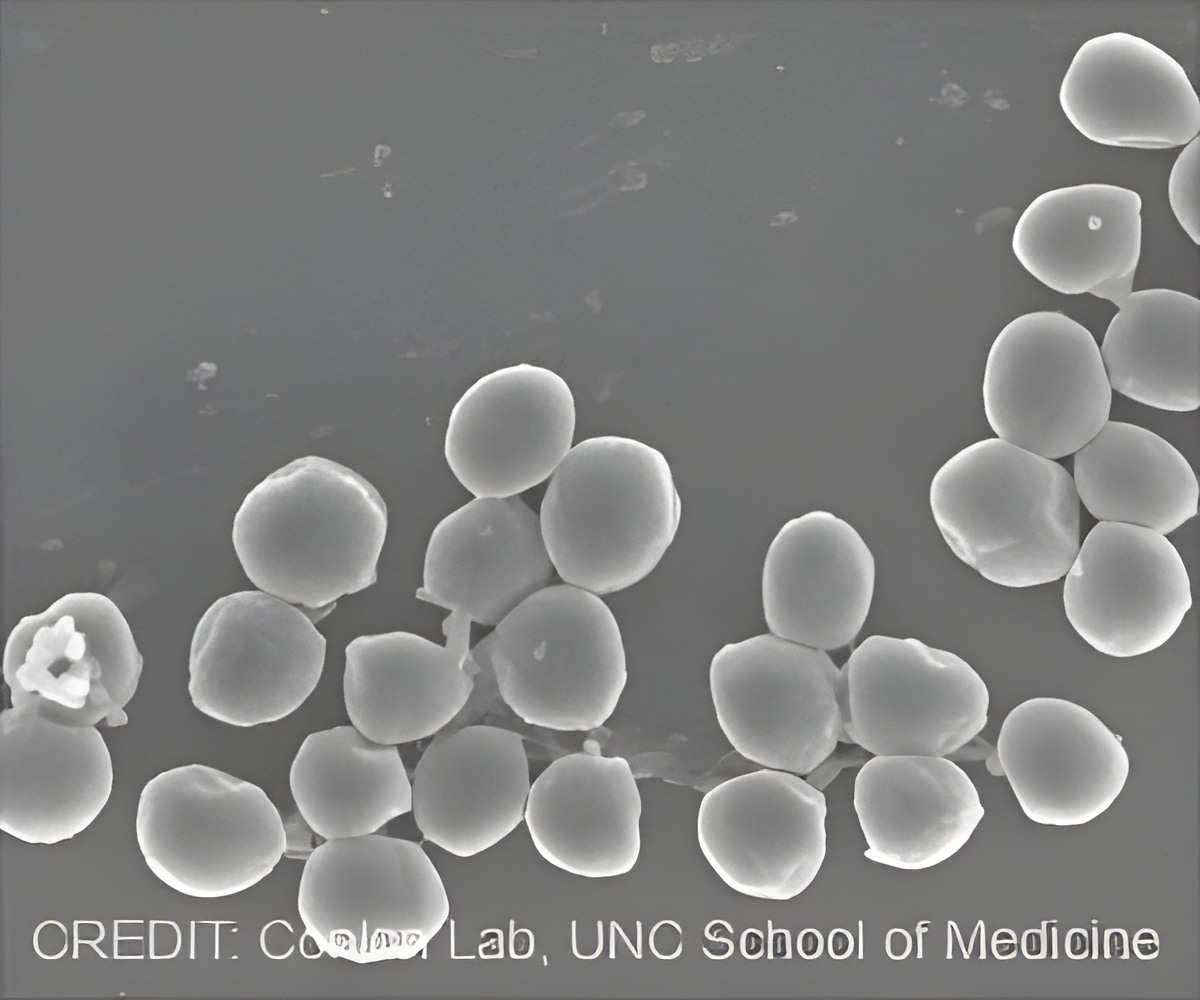

"The interactions with P. aeruginosa can completely change S. aureus's susceptibility to standard antibiotics," said study senior author Brian P. Conlon, PhD, assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at UNC.

Resistance to antibiotics by bacteria and other microbes is an ongoing public health crisis, contributing to about two million infections and 23,000 deaths per year in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. P. aeruginosa, for instance, is a multidrug-resistant pathogen associated with hospital-acquired infections, including ventilator-associated pneumonia. As for S. aureus¬, some strains do not cause disease. Others cause the classic "staph" infections that antibiotics do kill. Other strains, though, are antibiotic-resistant.

Researchers have been racing to find ways to overcome the resistance of these and other bacteria.

Advertisement

"We know that P. aeruginosa commonly co-infects with S. aureus and secretes factors that mess with S. aureus's metabolism," Conlon said. "So our hypothesis was that this interaction might be throwing S. aureus into a more antibiotic-resistant state."

Advertisement

The results were striking and have implications for clinical practice.

The P. aeruginosa factors affected S. aureus's susceptibility to all three antibiotics, in some cases to an enormous extent. Some strains of P. aeruginosa, as expected, significantly reduced S. aureus's susceptibility to tobramycin and ciprofloxacin. Surprisingly, though, many other strains of P. aeruginosa greatly enhanced S. aureus'ssusceptibility to antibiotics used in the experiments.

"Factors secreted by eight of the P. aeruginosa strains, for example, induced 100 to 1000 times more killing of S. aureus by vancomycin, compared to the control culture of S. aureus that was not exposed to P. aeruginosa factors," Conlon said.

The researchers identified three specific P. aeruginosa factors that accounted for these effects:

- A protein-cutting enzyme called LasA increased vancomycin's ability to kill S. aureus.

- A set of fat-related molecules called rhamnolipids increased S. aureus's uptake of tobramycin.

- A small organic molecule called HQNO inhibited the metabolism of S. aureus, shifting it into the low-energy state that made it more antibiotic-resistant.

Another approach would be to develop simple bacterial genetic tests that enable doctors to detect when a co-infecting bacterium is likely secreting factors that significantly influence antibiotic susceptibility.

Conlon's team is now sequencing P. aeruginosa strains to see how gene sequences vary between strains and how this variance affects the ability of these strains to produce the aforementioned factors Conlon's lab has described.

Source-Eurekalert