Treating malaria in pregnancy could be challenging. Check out the new updated WHO guidelines for malaria treatment in the first trimester of pregnancy to save mother and child.

‘Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are safe and effective in treating uncomplicated malaria during the first trimester of pregnancy.’

Read More..

Read More..

Advertisement

Treatment of Malaria in Pregnancy

The study provides compelling evidence that artemether-lumefantrine should now replace quinine as the treatment of choice in the first trimester. Although there is limited data on specific artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) other than artemether-lumefantrine, the other ACTs (including artesunate-amodiaquine, artesunate-mefloquine, and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine but not artesunate–sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine) may be considered for use where artemether-lumefantrine is not available, given the demonstrated poorer outcomes of quinine treatment, along with the challenges of adherence to a seven-day course of treatment.ACTs are already recommended for treatment in the second and third trimesters. This study, the largest of its kind, was a collaborative effort between over 20 research groups with data from over 34,000 pregnancies from 12 cohort studies in ten countries collected over more than 20 years.

Advertisement

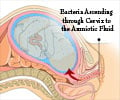

Is Malaria Common in Pregnancy

Malaria in pregnancy has devastating consequences for both mother and fetus, requiring prompt and effective treatment. The risk of infection is highest in the first trimester, when many pregnancies are yet to be protected by chemoprevention with intermittent preventive treatment (IPTp) which begins in the second trimester. Until now, the WHO recommended ACTs as first-line treatment in all patient groups, with the exception of first-trimester women, who should receive quinine with clindamycin due to concerns about artemisinin embryotoxicity.Advertisement

Improving Malaria Treatment During Pregnancy

The meta-analysis results suggest that first-trimester treatment with artemisinin-based treatment is as safe and possibly more effective than non-artemisinin-based treatments, including quinine-based regimens. Importantly, artemether-lumefantrine, the ACT with the most safety data, was associated with 42% fewer adverse pregnancy outcomes (pregnancy loss or major congenital malformations) than oral quinine in the first trimester.Dr. Stephanie Dellicour, Principal Research Associate at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, said: “The results of this meta-analysis are very reassuring, as studies have shown that many women are already being exposed to first-line ACT treatment in early pregnancy in malaria-endemic countries. This is partly due to a lack of awareness of pregnancy status by the patients or healthcare providers at the time of treatment and the fact that quinine and clindamycin are largely unavailable in health facilities in eastern and southern Africa.”

Dr. Makoto Saito, Assistant Professor at The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo and part of the WorldWide Antimalarial Research Network (WWARN), said: “At WWARN, we have previously shown that ACTs have a superior efficacy and much better tolerability and lower transmission risk after treatment than quinine. This new study provides an update on a previous study, confirming the evidence on safety in the first trimester using all the currently available clinical data.

“This study provides strong evidence to policy makers that ACTs should replace quinine-based regimens as the preferred treatment for uncomplicated falciparum malaria for everybody, including pregnant women in their first trimester.”

All participating research groups kindly agreed to share their individual patient data (IPD) of 34,178 pregnancies with WWARN. The data included 737 pregnancies with confirmed first-trimester exposure to artemisinin-based treatment and 1,076 with confirmed exposure to other antimalarials. It has taken over 20 years to collect these data, illustrating the difficulty of obtaining quality data on the safety of antimalarials in pregnancy.

Dr. Dellicour added: “Going forward, innovative strategies are needed to fast-track robust evidence generation to support informed decisions on treatment in pregnant women by policy makers, healthcare providers, and patients and ensure that this high-risk group has access to the best antimalarial treatment in a timely manner.”

Source-Eurekalert