Fibrocartilage tissue in the knee is comprised of a more varied molecular structure than researchers previously appreciated, according to a new study.

‘The fibrocartilage tissue in the knee is comprised of a more varied molecular structure than researchers previously appreciated, revealed this new study. This could lead to better treatments for injuries such as knee meniscus tears and age-related tissue degeneration.’

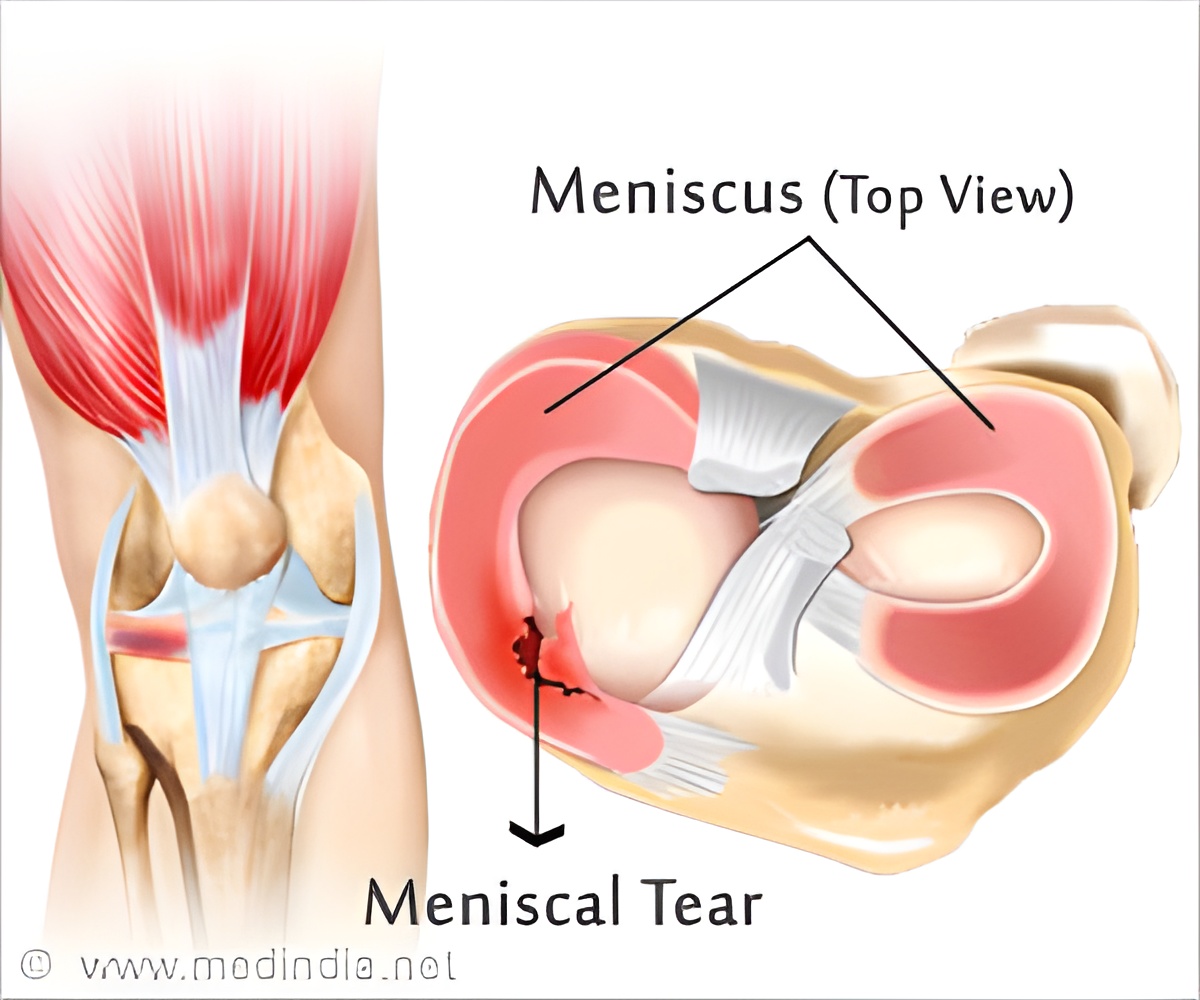

A new study by researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Delaware has suggested that fibrocartilage tissue in the knee is comprised of a more varied molecular structure than researchers previously appreciated. Their work informs ways to better treat such injuries as knee meniscus tears - treatment of which are the most common orthopedic surgery in the United States - and age-related tissue degeneration, both of which can have significant socioeconomic and quality-of-life costs. The research team published their work online in Nature Materials.

Co-senior author Robert L. Mauck, an associate professor of Orthopedic Surgery and Bioengineering at Penn, said, "To be able to probe natural tissue structure-function relationships, we developed micro-engineered models to advance our understanding of tissue development, homeostasis, degeneration, and regeneration in a more controlled manner. Our tissue-engineered constructs match the structural, mechanical, and biological properties of native tissue during the process of tissue formation and degeneration. Essentially, we are working to engineer tissues not just to provide healthy replacements, but also to better understand what is happening to cause degeneration in the first place."

The team describes that the meniscus tissues of knees are comprised of fibrous regions consisting of long, aligned fibers that give the tissue strength and stiffness. However, within this fibrous region are small non-fibrous regions called microdomains that have a different composition, with concomitant different mechanical properties. While the aligned fibrous regions transmit mechanical deformation signals directly to surrounding cells, the proteoglycan-rich microdomains do not deform at all.

"Our first question when we saw these microdomains was 'Are they normal, or are they associated with pathology?'," asked co senior author Dawn Elliott, professor and chair of Delaware's department of Biomedical Engineering.

Advertisement

The team surmised that cells in the fibrous regions and proteoglycan rich microdomains were not receiving the same mechanical signals. In fact, the cells within the microdomains did not respond to mechanical inputs, while cells in the fibrous regions switched calcium signals on and off in response to mechanical loading. These cells likely sensed the physical inputs when stretched - similar to stresses on muscles when exercising - and converted the mechanical input into a biochemical message, in this case calcium flow through the cell membrane.

Advertisement

"This engineered disease model will enable the development of new treatments for degenerative disease in numerous types of connective tissues," Mauck said.

Source-Eurekalert