A new noninvasive electric stimulation technique developed at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center can prove a boon to stroke patients who have lost motor skills in their hands and arms.

“We think that the key to this therapy’s success in improving stroke patients’ motor function is based on its ability to affect the brain activity on both the stroke-affected side of the brain and the healthy side of the brain as patients work to re-learn lost motor skills,” says senior author Gottfried Schlaug, MD, PhD, the Director of the Stroke Service in BIDMC’s Department of Neurology and Associate Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School.

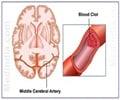

In the brain of a healthy individual, the left and right sides of the motor cortex work in tandem, inhibiting one another as needed in order to successfully carry out such one-sided movements as writing or teeth-brushing. But, explains lead author Robert Lindenberg, MD, an HMS Instructor of Neurology at BIDMC, when a person suffers a stroke (as might happen when an artery to the brain is blocked by a blood clot or atherosclerotic deposit) the interaction between the two sides of the brain involved in motor skills changes.

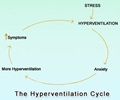

“As a result,” he explains, “the motor region on the unaffected side of the brain begins to exert an unbalanced effect onto the motor region of the brain’s damaged side.” And, as Schlaug and Lindenberg further explain, this leads to an increased inhibition of the stroke-damaged motor region, as the remaining intact portions of this region try to increase activity in the motor pathways to facilitate recovery.

tDCS is an experimental therapy in which a small electrical current is passed to the brain through the scalp and skull. Because previous studies had determined that tDCS could improve motor function if applied to either the damaged or undamaged side of the brain, Schlaug’s team hypothesized that applying tDCS to both sides — while simultaneously engaging the stroke patient in motor skill relearning activities — would further speed the recovery process.

“tDCS works by modulating regional brain activity,” explains Schlaug. “In applying this therapy to both hemispheres of the brain, we used one direction of current to increase brain activity on the damaged side, and used the reverse current to inhibit brain activity on the healthy side, thereby rebalancing the interactions of both sides of the brain.”

Advertisement

By using sophisticated MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) techniques, the researchers were able to “map” the positions of the stroke lesions in relation to the brain’s motor system. “This helped us to very closely match the two patient groups,” notes Schlaug. “Not only did the two groups of patients outwardly exhibit similar motor impairments, but we could tell from the MRIs that their lesions were positioned in similar areas of the brain. This novel approach strengthens the results, since no other between-group factor could explain the therapy’s effects.”

Advertisement

“This is the first time that stimulation therapy has been administered simultaneously to both brain hemispheres and coupled with physical/occupational therapy,” explains Schlaug. “Both sides of the brain play a role in recovery of function [following a stroke] and the combination of peripheral sensorimotor activities and central brain stimulation increases the brain’s ability to strengthen existing connections and form new connections. It is a testament of just how plastic the brain can be if novel and innovative therapies are applied using our current knowledge of brain function.”

This study was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Source-Medindia