Oncologists suggest that the word cancer must be removed from the description of low grade prostate cancer, in order to prevent overtreatment.

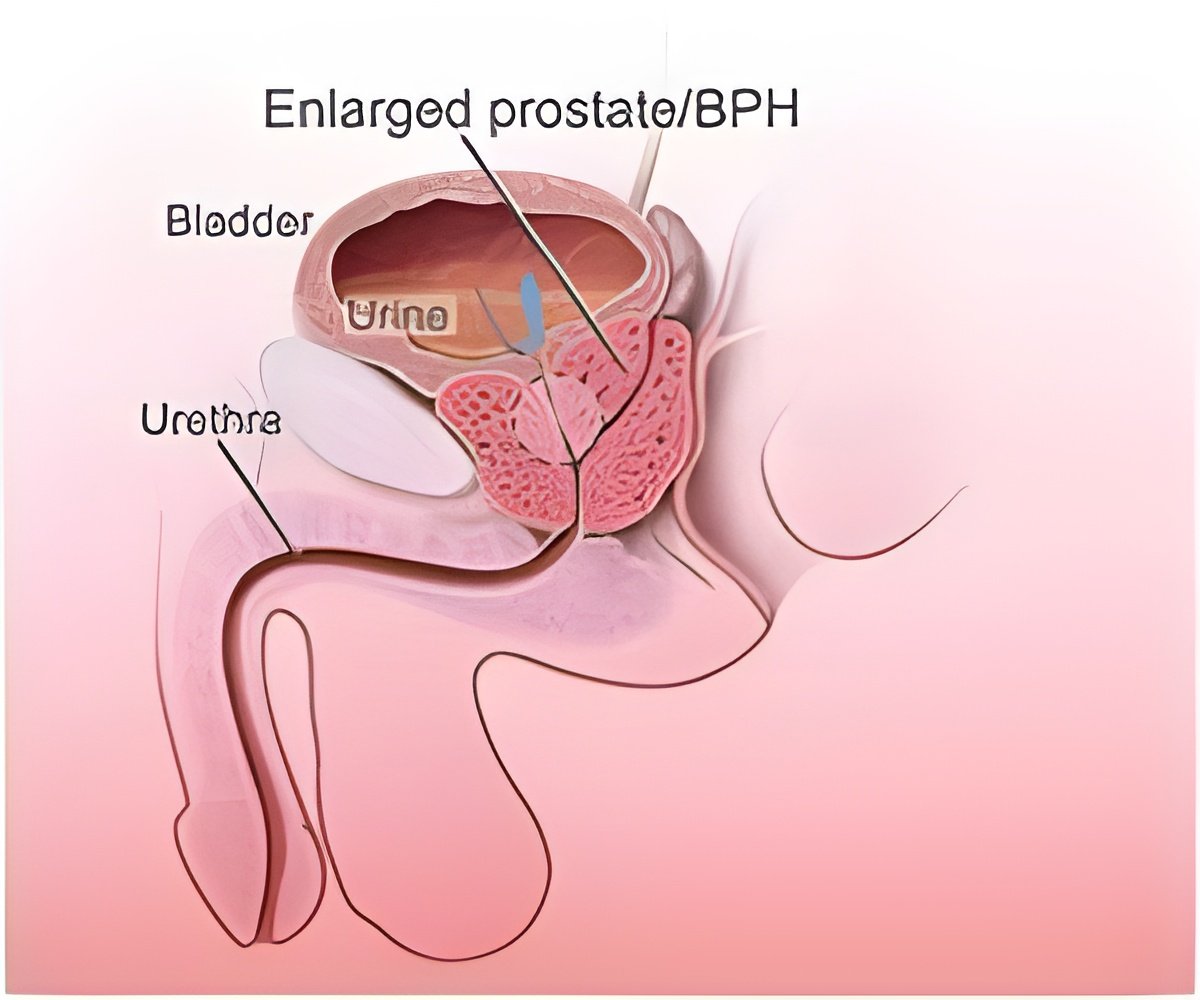

Dr. Yamoah, together with Timothy Rebbeck and colleagues from the University of Pennsylvania, looked at patients whose cancers were low to intermediate grade and who underwent surgery to remove all or part of their prostate. The surgery was important because often men are given a so called "biopsy" Gleason score of cancer severity based on 12 needle biopsies of the prostate gland. This method is imprecise, however, and may not accurately capture men with truly low risk cancers.

In order to bypass this issue, Dr. Yamoah and colleagues only analyzed the records of men whose cancers were confirmed to be low-grade after surgical removal via a so called "pathologic" Gleeson scoring system. This method looks at several cross-sections of the entire tumor, rather than relying on a spot test. The researchers found that even in these confirmed low-grade cancers, African American men were more likely to have disease progression and worse outcomes than Caucasian men. There was about a 10 – 15 percent difference in 7-year disease control in this low-grade group (90 percent disease control at 7 years for Caucasian men versus 79 percent in African American men).

Dr. Yamoah and colleagues stress that these findings are based on retrospective analysis, which looks at patient records, and that a prospective analysis will be more definitive in helping determine whether African American men with a low Gleeson score should receive more aggressive treatment. In the meantime, Dr. Yamoah is investigating the molecular fingerprint that would help identify the African American men at highest risk for disease progression compared with those for whom watchful waiting could still be the best option.

Source-Eurekalert

![Prostate Specific Antigen [PSA] & Prostate Cancer Diagnosis Prostate Specific Antigen [PSA] & Prostate Cancer Diagnosis](https://images.medindia.net/patientinfo/120_100/prostate-specific-antigen.jpg)