The intestinal worms, or helminths enable beneficial microbes in the intestines to outcompete bacteria that promote inflammation.

‘Mice infected with intestinal worms significantly increased the number of Clostridia, a bacterial species known to counter inflammation.’

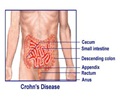

Researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center found that a specific kind of intestinal worm is more common in communities where inflammatory bowel disease rates are lower. The researchers decided to test if the parasites could be an effective treatment for people suffering from Crohn's disease. Crohn's causes inflammation in the lining of the digestive tract. It causes symptoms like abdominal pain, severe diarrhea, fatigue, weight loss and malnutrition.

Study co-author Ken Cadwell, assistant professor of microbiology at New York University School of Medicine, said, “Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been on the rise in the developed world, and that's what inspired the research.”

"There is this dichotomy in places like the U.S. and Western Europe where there are higher incidences of IBD compared to places like India and Southeast Asia," said Cadwell.

Cadwell and his colleagues used animal models to see if worms might restore a more balanced array of microbes in the gut.

Advertisement

Mice that were deficient in a gene called NOD2 were fed 10 to 15 parasitic whipworm eggs. The gene NOD2 is linked to Crohn’s disease. After the worms had matured, the researchers measured the amount of Bacteroides and Clostridia in the intestines and stool of the mice.

Advertisement

"When we infected the mice with the worms, sure enough, it reversed the disease. When we tried to see how that was happening, we saw differences in the microbiota," said Cadwell.

The researchers noted that the immune response to the worms might trigger the growth in Clostridia.

But, Cadwell said, "The worm infection might only work in certain people and not all IBD patients. We were looking at a specific genetic model using these mice."

“The worms were causing an immune response, secreting a beneficial mucus. We're getting a glimpse into how parasites may be giving a beneficial response. That is what we think is the beneficial effect of the parasite."

“The goal would be to take what's good from the parasite, isolate it, and give people the benefit without the parasite. Ideally, we want to see if we can mimic the effect of the parasite," said Cadwell.

The researchers also compared the bacteria found in 75 people from rural Malaysia to the bacteria of 20 people living in that country's urban capital, Kuala Lumpur. They found that rural people who are more likely to harbor parasites had far fewer Bacteroides than city dwellers. The same differences were seen between urban and rural populations in other Asian countries.

Dr. Arun Swaminath, director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, said, “The research is especially intriguing because there is no cure for Crohn's disease. Current treatments are aimed at fighting inflammation. Drugs include anti-inflammatory medicines, immune system suppressors, and antibiotics, as well as other medications for symptoms.”

"There are more bacteria than the human cells in our body -- we're just starting to understand this is a significant contribution to our world," said Swaminath.

"The next step is to see what happens in humans and do you recreate the same bacterial composition? Is it the worm treatment that is changing the microbiome, the bacterial composition -- is that the pathway? Or is it something unique to the worm itself?" he said.

The study is published in the journal Science.

Source-Medindia