Surgeons don't have a very good way of knowing when they're cutting out a tumor, they use their sense of sight, touch and pre-operative images of the brain.

‘A handheld, miniature microscope being developed by University of Washington mechanical engineers could allow surgeons to "see" at a cellular level in the operating room.’

But a handheld, miniature microscope being developed by University of Washington mechanical engineers could allow surgeons to "see" at a cellular level in the operating room and determine where to stop cutting. The new technology, developed in collaboration with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Stanford University and the Barrow Neurological Institute, is outlined in a paper published in January in the journal Biomedical Optics Express.

"Surgeons don't have a very good way of knowing when they're done cutting out a tumor," said senior author Jonathan Liu, UW assistant professor of mechanical engineering. "They're using their sense of sight, their sense of touch, pre-operative images of the brain -- and oftentimes it's pretty subjective."

"Being able to zoom and see at the cellular level during the surgery would really help them to accurately differentiate between tumor and normal tissues and improve patient outcomes," said Liu. The handheld microscope, roughly the size of a pen, combines technologies in a novel way to deliver high-quality images at faster speeds than existing devices. Researchers expect to begin testing it as a cancer-screening tool in clinical settings next year.

For instance, dentists who find a suspicious-looking lesion in a patient's mouth often wind up cutting it out and sending it to a lab to be biopsied for oral cancer. Most come back benign. That process subjects patients to an invasive procedure and overburdens pathology labs. A miniature microscope with high enough resolution to detect changes at a cellular level could be used in dental or dermatological clinics to better assess which lesions or moles are normal and which ones need to be biopsied.

Advertisement

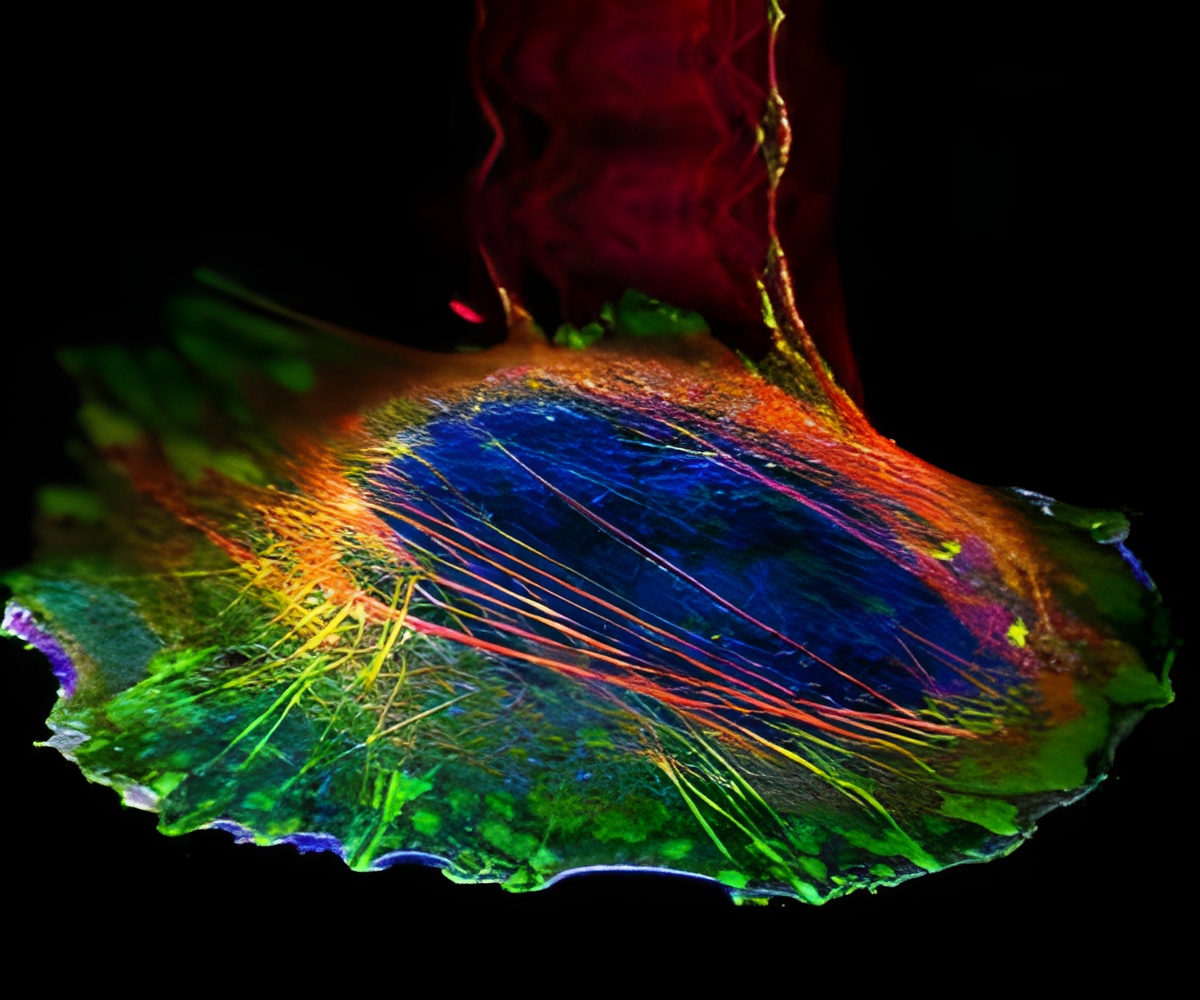

Making microscopes smaller, however, usually requires sacrificing some aspect of image quality or performance such as resolution, field of view, depth, imaging contrast or processing speed. "We feel like this device does one of the best jobs ever -- compared to existing commercial devices and previous research devices -- of balancing all those tradeoffs," said Liu.

"Trying to see beneath the surface of tissue is like trying to drive in a thick fog with your high beams on - you really can't see much in front of you," Liu said. "But there are tricks we can play to see more deeply into the fog, like a fog light that illuminates from a different angle and reduces the glare."

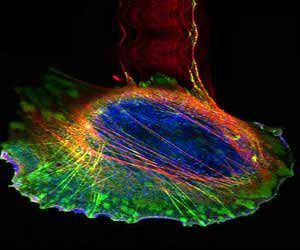

The microscope also employs a technique called line scanning to speed up the image-collection process. It uses micro-electrical-mechanical -- also known as MEMS -- mirrors to direct an optical beam which scans the tissue, line by line, and quickly builds an image. Imaging speed is particularly important for a handheld device, which has to contend with motion jitter from the human using it. If the imaging rate is too slow, the images will be blurry.

In the paper, the researchers demonstrate that the miniature microscope has sufficient resolution to see subcellular details. Images taken of mouse tissues compare well with those produced from a multi-day process at a clinical pathology lab -- the gold standard for identifying cancerous cells in tissues. The researchers hope that after testing the microscope's performance as a cancer- screening tool, it can be introduced into surgeries or other clinical procedures within the next 2 to 4 years.

"For brain tumor surgery, there are often cells left behind that are invisible to the neurosurgeon. This device will really be the first to let you identify these cells during the operation and determine exactly how much further you can reduce this residual," said project collaborator Nader Sanai, professor of neurosurgery at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix. "That's not possible to do today."

Source-Eurekalert