Often doctors are forced to place lifesaving defibrillators entirely outside the heart, rather than partly inside in the small size and abnormal anatomy of children born with heart defects.

A description of the team's work is published ahead of print in The Journal of Physiology.

"Pediatric cardiologists have long sought a way to optimize device placement in this group of cardiac patients, and we believe our model does just that," says lead investigator Natalia Trayanova, Ph.D., the Murray B. Sachs Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Johns Hopkins. "It is a critical first step toward bringing computational analysis to the pediatric cardiology clinic."

If further studies show the model has value in patients, it could spare many children with heart disease from repeat procedures that are sometimes needed to re-position the device, says co-investigator Jane Crosson, M.D., a pediatric cardiologist and arrhythmia specialist at the Johns Hopkins Children's Center.

"It's like having a virtual electrophysiology lab where we can predict best outcomes before we even touch the patient," Crosson says.

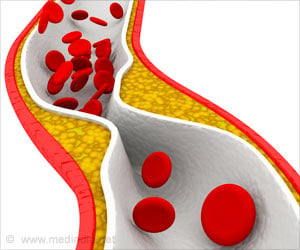

In adults and in children with normal size and heart anatomy, one part of the device lies under the collar bone, while the other end is inserted into one of the heart's chambers, a standard and well-tested configuration. But in children with tiny or malformed hearts, the entire device has to be positioned externally, an often imperfect setup. Such less-than-precisely positioned defibrillators can fire unnecessarily or, worse, fail to fire when needed to shock a child's heart back into normal rhythm, experts say. In addition, devices that are not positioned well can pack a punch, delivering ultra-strong, painful jolts that frighten children and could even damage heart cells.

Advertisement

With the Johns Hopkins heart model, scientists say they can find exactly where in relation to a patient's heart the device would be best able to reset the heart by using the least amount of energy and gentlest shock. This translates into longer battery life for the device as well, Trayanova says.

Advertisement

A particular advantage of the model is its true-to-life complexity. The model was built using digital representations of the heart's subcellular, cellular, muscular and connective structures — from ions and cardiac proteins to muscle fiber and tissue. The computer model also included the bones, fat and lungs that surround the heart.

"Heart function is astounding in its complexity and person-to-person variability, and subtle shifts in how one protein interacts with another may have profound consequences on its pumping and electric function," Trayanova says. "We wanted to capture that level of specificity to ensure predictive accuracy."

Trayanova and her team also have designed image-based models that pinpoint arrhythmia-triggering hot spots in the adult heart muscle and can help guide therapeutic ablation of such areas. The new pediatric virtual heart, however, is the team's first foray into pediatric cardiology.

Source-Eurekalert