A chemical widely used to make plastic bottles and food containers may come from non-food sources and linger in the body longer than commonly thought, a new study published Wednesday showed.

A chemical widely used to make plastic bottles and food containers may come from non-food sources and linger in the body longer than commonly thought, a new study published Wednesday showed.

Researchers from the University of Rochester in New York state said their new findings on bisphenol-A (BPA), linked by numerous previous studies to a range of serious ailments including prostate cancer, diabetes and heart disease, are key to understanding the chemical's toxicity.Until now "scientists believed that BPA was excreted quickly and that people were exposed to BPA primarily through food," said the study's authors, published online in the Environmental Health Perspectives journal.

The US Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority declare BPA to be safe partly on these assumptions, said the researchers.

"Our results simply do not fit that picture," insisted lead author Richard W. Stahlhut from the Rochester's Environmental Health Sciences Center.

"The research community has clues that could help explain some of these results but to date the importance of the clues have been underestimated. We must chase them much more vigorously now," he said.

Researchers at Rochester sought to find out the link between the concentration of BPA in urine and the length of time spent fasting from food. The study analyzed data collected from 1,469 adults and found that "surprisingly high levels remain in the body even after fasting for as long as 24 hours."

Advertisement

According to the researchers the most plausible explanations that could explain higher-than-expected BPA is that exposure does not actually come from food, but rather through other means such as house dust or tap water.

Advertisement

In a September report published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, scientists found that adults with the highest concentrations of BPA in their urine had nearly triple the odds of cardiovascular disease, compared with subjects found to have the least amounts of the compound in their systems.

Authorities in Canada have already outlawed BPA as a health risk and major environmental contaminant.

In October a scientific advisory board impaneled by the FDA to review the agency's procedures for assessing the chemical's risk found that federal regulators used a flawed methodology and failed to heed numerous reports linking the substance to a number of serious ailments.

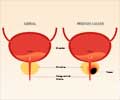

The panel accused the FDA of ignoring the results of studies done on animals showing that small doses of BPA could provoke changes during development in the brain and prostate glands.

Some scientist called for banning the chemical altogether.

"The current levels of exposure are not safe," said Sarah Janssen, a reproductive biologist with the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental advocacy group.

"We should get rid of it in food containers."

Officials at the FDA, which regulates the chemical's use in containers and food ware, acknowledged the criticism.

"FDA agrees that due to the uncertainties raised in some studies relating to the potential effects of low doses of bisphenol-A that additional research would be valuable," the agency said at the time.

Source-AFP

SRM