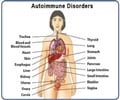

It is quite well-known that the immune system recognizes and neutralizes or destroys toxins and foreign pathogens that have gained access to the body.

Multiple sclerosis is a common and, in many cases seriously disabling, autoimmune disease that can lead to the disturbance or loss of sensory function, voluntary movement, vision and bladder control. Commonly, it is thought that the primary target of MS is the myelin sheath, an insulating membrane that enwraps axons, and increases the speed of signal transmission. However, damage to nerve fibers is also a central process, as whether autoimmune pathology ultimately leads to permanent disability depends largely on how many nerve fibers are damaged over the course of time.

The team led by Kerschensteiner and Misgeld set out to define precisely how the damage to the nerve axons occurs. As Misgeld explains, "We used an animal model in which a subset of axons is genetically marked with a fluorescent protein, allowing us to observe them directly by fluorescence microscopy." After inoculation with myelin, these mice begin to show MS-like symptoms. But the researchers found that many axons showing early signs of damage were still surrounded by an intact myelin sheath, suggesting that loss of myelin is not a prerequisite for axonal damage.

Instead a previously unrecognized mechanism, termed focal axonal degeneration (FAD), is responsible for the primary damage. FAD can damage axons that are still wrapped in their protective myelin sheath. This process could also help explain some of the spontaneous remissions of symptoms that are characteristic of MS. "In its early stages, axonal damage is spontaneously reversible," says Kerschensteiner. "This finding gives us a better understanding of the disease, but it may also point to a new route to therapy, as processes that are in principle reversible should be more susceptible to treatment."

However, one must remember that it takes years to transform novel findings in basic research into effective therapies. First the process that leads to disease symptoms must be elucidated in molecular detail. In the case of MS it has already been suggested that reactive oxygen and nitrogen radicals play a significant role in facilitating the destruction of axons. These aggressive chemicals are produced by immune cells, and they disrupt and may ultimately destroy the mitochondria. Mitochondria are the cell's powerhouses, because they synthesize ATP, the universal energy source needed for the build-up and maintenance of cell structure and function.

"In our animal model, at least, we can neutralize these radicals and this allows acutely damaged axons to recover," says Kerschensteiner. The results of further studies on human tissues, carried out in collaboration with specialists based at the Universities of Göttingen and Geneva, are encouraging. The characteristic signs of the newly discovered process of degeneration can also be identified in brain tissue from patients with MS, suggesting that the basic principle of treatment used in the mouse model might also be effective in humans.

Advertisement

Advertisement